There are many things to admire about David Lee Roth's home. There's the lushly landscaped property, three football fields' worth by his estimation, hidden behind a 9-foot ivy-covered wall on an otherwise undistinguished suburban Pasadena block. There's the house itself, which he's had for 25 years, a sprawling 1920s Spanish-style mansion with 13 rooms in the basement alone. There's the tennis court in back, filled with a foot and a half of sand to accommodate beach barbecues — he doesn't play tennis. But Roth's favorite thing about his home might be the floors. They are important.

"Feel this?" He stamps his foot a few times. "That transfer of shock? The floor has to have some give to it. It's why you don't do ballet on concrete." The effect is much like the inch-thick wooden plank, maybe 15 feet by 15 feet, that comprises the center of Van Halen's stage, where he plies a very specific trade. Acrobatic high-kicks and shimmies. Martial-arts maneuvers and sashays. "I have moves onstage it took me two years to learn."

There is nothing actually on most of the floors in the house. The living room is bare, save for a few framed photos from the cover shoot of the first Van Halen album hanging crooked in one corner. ("I'm not much of a furniture collector, and I'm not much of an interior decorator.") A ceiling-high built-in china cabinet is empty. Half a bottle of Jamaican rum rests on the mantle, and on the far wall is a rack of Japanese katana swords.

"The real deal," he says, unsheathing one. "Razor sharp. The first time I held one of these swords, I was maybe 9 years old." He demonstrates a few moves, alternately fluid and severe. "Everything has to be internalized or you'll look stiff. Once you can do it physically, it becomes your personality." He's decked out in the now standard offstage getup of mustard-colored overalls he started wearing three years ago while building stage props around the house — a samurai Mario brother.

"I just had my sword teacher here from Tokyo," he says, rat-a-tat, as he says nearly everything. "Buddhist monk, about my age. He loves two things about Southern California: the chopped liver from the Jewish delicatessen and these floors. Mojo Dojo. You ever hold one of these?" I have not.

He places the sword in my hands and I instantly feel dumb. There's a weight to it that only expensive things have, and I'm not quite sure what to do. "Have you ever cut anything with these?" I ask dumbly. He has not; maybe an apple on a string once. I start to swing it tentatively and I can see him wincing out of the corner of my eye. I hand the sword back to him more carefully than I've ever done anything.

There is a not insignificant population for whom David Lee Roth is the ur-rock star, the embodiment of everything splendorous and stupid about that term, as responsible as anyone for establishing, defining, and cementing the debauched libertine, hotel room-trashing, groupie-defiling caricature that is cliché and passé and lionized. Roth is a little less famous for having parlayed that caricature into a life that's rich and weird and singular and driven by very particular and exotic enthusiasms ranging from mountain climbing to martial arts to tending to gunshot victims in the Bronx. But this is something he's actively trying to change. He owes this movable feast to leaving — quitting, getting kicked out of: pick your version of the legend — what was, at the time of his messy exit, the biggest, most over-the-top band in the world. If not for that, he might not be someone who, at 57, would train to be a master swordsman or to speak fluent Japanese.

"I wonder who I might have been had I stayed in the band," he says. "Not as interesting, not as involved. I probably would have followed the more traditional, long, slow climb to the middle. Enjoying my accomplishments, living off my residuals. I wouldn't have half the stories to tell."

And if not for the fact that Roth rejoined Van Halen in 2007, thus ending rock's most enduring will-they-or-won't-they soap opera, he wouldn't be in the position to try to channel that experience into a sprawling one-man video series and podcast that aspires to do nothing less than tell the history of modern culture through the eyes of someone who has been everywhere, done everything, met everyone, and hired a couple of midgets to be his security detail along the way. He's going to use the internet to save us from the internet. He does not harbor any illusion that his life is easily replicated — celebrities, they aren't just like us — but he would like to, as humbly as one can do such a thing, offer it as an example of what a life can be.

"I know what compels me, I know what I'm made of culturally," he says. "It's a variety of neighborhoods. It's Spanish speaking. It's jock. It's graphic arts. It's surfing. It's Hell's Angels. It's Groucho Marx, it's Kurosawa. Throw in some Kenny Chesney. Hey, are you speaking Creole? Great, throw that in too. And not all neighborhoods compel me, I'm not one world, one love." He places the sword back on the wall.

"I'm an eye and an ear into a world and a wealth of experience that we're all part of simply by virtue of watching television," he says. "If indeed we live in a Beyoncé world, then this is a view into aspects of that that are rarely discussed and rarely explained. This is of infinite interest to a lot of my colleagues in the fine arts, well and beyond any specific kind of music or part of show business. The stars I see in a lot of people's eyes are because of the uniform, not because of the pilot inside."

David Lee Roth has seen some shit and he has to tell you about it. All of it. The hot for teacher has become the teacher.

The house is sparse and drafty — Roth leaves all the windows open at all times, regardless of weather, to help remain in tune with nature. He lives here alone with Russ, his 7-year-old Australian cattle dog, currently at his side; when there is band business to attend to, it's attended to here by production staffers and assistants, and his sister lives in the suite above the garage. He still has a place in New York City and has spent much of the past year at his new apartment in Tokyo. "This house is the only real tangible thing I ever bought, and I only paid it off, like, two years ago. Beyond that, I own three black pickup trucks of varying sizes, depending on the livestock we're moving."

Early on a Saturday night in March, the house is empty and quiet. The overall effect is more Sunset Boulevard than Citizen Kane or Grey Gardens, although his kerchief game is legendary. At the bottom of the grand staircase, in the dark foyer with black-and-white marble floors, Roth instead offers, unprovoked, "It's very end of There Will Be Blood."

Maybe he's heard every question. Maybe he's had the time to anticipate every question. "The only thing missing is the log cabin: 'Howdy, y'all lost?' We gotta have company more often, whaddya think, Russ?"

The solitude is by careful design, as is nearly everything else about Roth's existence. Before his family wound up in Pasadena, they moved around a lot — Indiana, Massachusetts — and he's said in the past that he decided by a young age that he would never have a steady group of friends. "I was clearly mopey as a kid," he says. "But feeling sorry for yourself is a great motivator. I have a handful of very good friends, and I'm lucky enough to have them in different locales. The closest I have to a show business friend is Konishiki, a 600-pound ex-sumo wrestler in Tokyo. He's my language mentor."

Seeing his parents split up in high school didn't really endear Roth to the notion of the nuclear family as an aspiration. (Google "david lee roth + married" and the first result is a rumor buried in some metal message board that he married his male chef in a civil ceremony a decade ago; this elicits a proper guffaw, he's never heard this one.) "I've lived alone my whole adult life. I've had girlfriends, I've had love affairs. Never longer than a year and a half. I'm the drunk who won the lottery, I'm going to be very difficult to convince of a lot of traditional things. I put off getting married when I found out, oh, you don't really have to. I just saw somebody discussing this recently, I think Gloria Steinem — same thing as her life story. There's a lot of us out there."

The centerpiece of the downstairs hallway is a relic from a louder time: the front grill of the rickety Opel Kadett station wagon Roth drove when Van Halen were just starting out in the mid-'70s playing bars and parties around L.A., bolted to the wall with the back half of a stuffed deer rammed through the windshield. Alex and Eddie Van Halen were acquaintances then — never quite friends, exactly — also from Pasadena, classically trained prodigies who needed Roth's innate showmanship as much as he needed their chops. By the time Van Halen's debut went gold in 1978, Roth was squiring himself around Hollywood in a pearlescent black Mercedes SEL adorned with a giant skull and crossbones on the hood, complete with flames and a 24-karat gold-leaf tooth. "It was a statement of some sort," he says. "I was a favorite of parking attendants all over town."

Van Halen released six albums in six years, the last of which, 1984, was their breakthrough. In 1983, they headlined Steve Wozniak's US Festival in California to 350,000 people and were paid a million dollars, more than any band ever for a single show. Not much more than a year later, they were in shambles, rock's most dramatic divorce. Years of continued commercial success without Roth in the band through the '80s diluted the brand, replacing Roth's wink and a nudge with a sledgehammer.

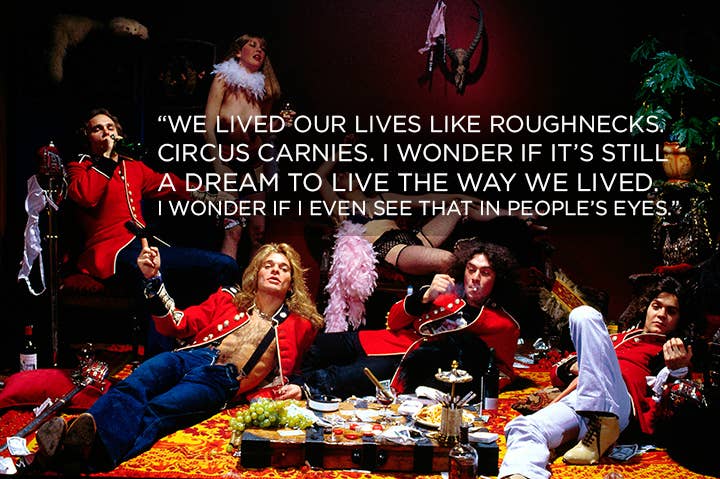

"We lived our lives like roughnecks," he says. "Roustabouts, circus carnies. I wonder if it's still a dream to live the way we lived. I know the success part of it is. Not just the partying, but the travel, the late nights, not just with groupies, but with all kinds of colleagues in a variety of other pursuits. I wonder if I even see that in people's eyes."

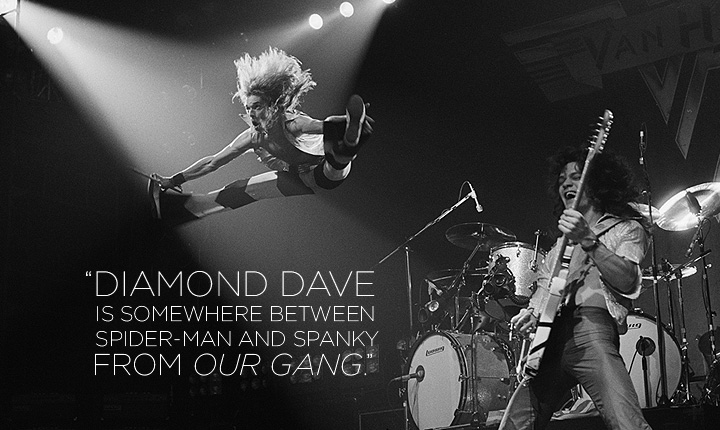

There is no point in pretending that I didn't have the Van Halen poster over my bed with this guy frozen in an eternal mid-air split, or that I didn't hurt myself repeatedly trying to strike that pose while jumping off swings: face forward, mouth in an "o," hands pointing down and center. The point is not that an 11-year-old tried to impersonate him, it's that he was someone an 11-year-old would try to impersonate. He was rock star as superhero, a human cartoon — Diamond Dave. It was impossible to imagine having a normal conversation with him, and once that becomes your working definition of a rock star, it is a difficult thing to shake.

The Fabulous Picasso Recording Brothers sign from the beginning of 1986's "Goin' Crazy" video hangs by the Opal Kadett sculpture, alongside some framed movie posters stacked and leaning against the wall. On the other side of the hall is giant framed print of the cover of Eat 'Em and Smile, while a life-size shot of the photo from the cover of 1987's Skyscraper, which shows Roth scaling the side of a mountain, hangs by the stairs, in case you just came to and are wondering whose house you're in.

It was the immediate post-Van Halen stretch in the mid-'80s that Roth considers his most decadent — he calls it his "F. Scott Fitzgerald period" because of the increasingly elaborate parties and groupie-wrangling protocols — free of even the pretense of band diplomacy, pushing the cartoon to its logical extreme, playing up the old-soul vaudeville act that was always on the fringes of Van Halen and the strutting id that was always at its center. "Just a Gigolo" and "California Girls" were pop-friendly MTV staples and made Roth seem like something much bigger than the singer in the world's biggest rock band. A movie deal fell through, and, maybe surprisingly for such an obvious ham, Roth never felt compelled to further pursue the Hollywood route. Between Van Halen and his '80s solo albums, he's sold 42 million records worldwide; this is a metric that's lost meaning over the past decade, but by any measure, it's a lot. It's no-one's-ever-going-to-do-that-again a lot.

"Diamond Dave is somewhere between Spider-Man and Spanky from Our Gang," he says, popping open a beer. He's never made a point of apologizing or renouncing past clownishness, never showed regret or embarrassment, never worried about those who didn't get the joke, never OD'd or got sober, never got busted for anything more than a dime bag. "I went through a wild phase where I was that person, and perhaps one hurdle is allowing yourself to develop. Everybody goes through the Harley-Davidson phase, the leather days — that's a great merit badge, and the hardest phase to live through."

A close second, though, is a familiar bugaboo to anyone who went platinum in the go-go '80s and found their teased hair and casual hedonism mocked and dwarfed by a dressed-down, purposefully glum zeitgeist. "Two words: Kurt Cobain. I went from playing to 12,000 people to 1,200. From arenas to casinos and state fairs and the local House of Blues. That will cause you to reflect a lot more clearly on your values. Fun wasn't seen as fun anymore." Rather than fight the turn toward cultural irrelevance, he steered into it, especially after a prospective and much ballyhooed 1996 Van Halen reunion imploded before it began. Settling down was no more appealing an option than it had ever been ("I'm 35 and gotta start over, maybe not the best time to start a family, but if you don't want to start a family, then any time is not a good time to start a family"). He eventually became a certified EMT in New York and then completed a tactical medicine training program in Southern California. Not famous enough to headline Madison Square Garden, plenty famous enough to stand out in a tactical medicine training program.

"The altitude drop is when somebody realizes who you are and they take you to task. Now you're the guy who gets to do garbage five days in a row instead of one, and doing ambulance-garage garbage is different from I-just-finished-dinner-and-now-I-have-to-dump-the-garbage-darling garbage. That will test you. But I was old enough and smart enough to know what I'd signed up for. These tactics are of value, they're a contribution."

For years he went on ambulance calls all over New York City, and found that a life in the music business was good preparation for rushing to the aid of grievously injured people in the less picturesque corners of the city. "My skills were serious," he says. "Verbal judo, staying calm in the face of hyper-accelerated emotion. Same bizarre hours. Same keening velocity."

Roth is clearly proud of how he's handled 35 years navigating himself in and out of some very bright spotlights and doesn't begrudge those who may have been less adept. "Up until the past few years, I don't know that Edward was someone who enjoyed any of his celebrity," he says of his once and future costar and frenemy, who married One Day at a Time's Valerie Bertinelli and basically became the Ben Gibbard and Zooey Deschanel of the '80s. "His last name right away is a trumpet. I knew how to use my name to get a good table at a restaurant but also how to use it so you won't recognize me when I'm there. Nine times out of ten I'm sitting next to you and you have no idea. People are surprised by the degree to which I've relinquished the attention, but I was taught this. You gotta learn to exist in both worlds. Uncle Manny taught me this."

Manny Roth is to Diamond Dave as Alfred is to Batman. The brother of Roth's late ophthalmologist father Nate, Manny owned jazz club Café Wha? in Greenwich Village in the early '60s and booked some of the first shows for up-and-comers Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, and Woody Allen. He gave Richard Pryor his first shot and became his first manager.

"David's father would bring him down when he was 7, 8, 9, 10 years old, and I would give him the royal treatment," says Manny, now 93, on the phone from his home in Ojai, California. "I used to fix him up with ice cream, whatever he wanted. I didn't try to turn him onto anything, but maybe it was osmosis. I was in the center of the scene there — all you had to do was carry an empty guitar case and the girls would follow you. I did my share of drugs. I had my long hair and all that crap. Every day was an adventure."

By 1974, Manny was divorced with three kids and strung out and in debt, which is about as boilerplate a rock 'n' roll narrative as they come, then pulled himself together and ran another nearby club, the Village Gate. He takes pains to credit Roth's parents for being the type of people who encouraged the pursuit of any interest — but osmosis is a powerful thing to an impressionable child bearing ice cream. "By and large, David's stories are the same stories I tell," he says. "From day to day, his life is a new adventure, he's a superstar. He's in Japan learning the language and the jujitsu. He doesn't sit on his ass. I asked him how are the Japanese ladies over there and he said he'd send me one. I love him dearly. I know he can be a little quirky."

How so?

"Being a rock star is being a rock star, I don't need to go into the details. What would you do if you were a rock star?"

Roth opens the door to the downstairs study, filled with rows and rows of wardrobe racks and lorded over by an 8-foot statue that he's decorated with Japanese tattoos, another interest he's engaged with characteristic vigor. If you're in need of a yellow embroidered matador jacket but aren't sure what kind of yellow embroidered matador jacket, have we got a room for you. Road cases are scattered on the patio outside the study — after nearly a year of unplanned dormancy owing to Eddie Van Halen's bout with diverticulitis that scrapped what had been one of the most successful tours of last year, the machine is cranking up again. There's a one-off show in Australia in April, Japan in May, and a festival in Wisconsin in July.

"I've read all these," he says, gesturing to the swollen bookshelves. The most important one he's read recently is Christopher Hitchens' memoir Hitch-22. He refers to the art books regularly, overseeing design needs for Van Halen. "I look forward to the longer flights because I'm actually able to read a full paperback uninterrupted. Here there's a barrage of stimuli: the phone, email. Books shaped who I am early on — Jack London, Mark Twain. All those adventure magazines, like Argosy. Guys who went out into the territory and became merchant marines or opened up a bar somewhere in the South Pacific but then somehow came to own banana fields in Ecuador and then and then and then. And now I'm writing The Innocents Abroad in cyberspace."

When Howard Stern left for satellite radio in 2006, Roth took over his time slot — his first guest was Uncle Manny — but almost immediately bristled against what he thought was a restrictive format. The idea of parlaying his loquaciousness into something approaching a day job isn't anything new. He's excited by the prospect of no one telling him what can or can't work.

Just as reading Jack London books as a child fueled his wanderlust, he's trying to pass this tradition on, using his own war stories to educate a generation driven to complacency. A generation that may not necessarily know who he is. He wants to be stopped by fans who tell him he inspired them to go to Borneo as much as he's stopped by fans who tell him he inspired them to start a band.

The upstairs hallway is lined with platinum records — and platinum cassettes, god bless — monuments to the kind of career a rock band would barely think to aspire to today. At a moment when Mumford and Sons can fairly be called one of the biggest bands in the world, it's hard to understate the relative ubiquity and range Van Halen possessed — highbrow and lowbrow, butch and flamboyant, appealing to stoners and jocks, men and women, boys and girls. Who else would Jeff Spicoli hire to play his birthday party?

Sitting in the upstairs office, Roth fishes a Marlboro Light out of a pack and tosses it back onto a small wooden school desk — they're good for what he calls his "rusty pipe" of a voice. Lolita Holloway plays on a loop from a stereo in another room. CDs and DVDs line the bookshelves in woozy, haphazard stacks, Russ' crate sits next to a bowl of water and an exercise bike. On the wall by the bathroom door are scribbles that look from a distance like height markings for a growing child, but they're actually ideas and song titles, chicken scratch. The windows open out onto the vast backyard as the sun goes down. "It's the last refuge of the great outdoors without having to leave the city. You're not going to find this in Beverly Hills."

In December 2011, Roth posted an eight-minute black-and-white video scrapbook, compiled with the help of editor Shelly Toscano, that served as a de facto (re-)introduction to Roth and his interests. Another, showing Roth herding dogs, was shown during breathers on last year's Van Halen tour. Toscano came on to work for Roth full-time, primarily editing Van Halen promo materials, but his inherent hamminess had discovered a new outlet and a new purpose.

Last October, The Roth Show launched: It's a YouTube series shot at the house or on the road, with an audio version available as a podcast, and it's nothing more or less than David Lee Roth speaking for a half hour on, more or less, a single topic. Tattoos. FM and underground radio. The history and semiotics of pop videos by way of Picasso. A long-ago trip to New Guinea. His personal history with drinking and smoking. Slideshows from an unending vacation. The episodes are monologues, history lessons, personal taxonomy, but really, mostly just talking and more talking, social-studies lectures by way of rock 'n' roll Babylon, at carnival-barker cadence. He speaks in dog years. He is the Ken Burns of David Lee Roth.

The effect is overwhelming. The show has already amassed hours of Roth unpacking himself, and it's hard to think of any figure of his status, in any field, who has put himself or herself out there to this degree, unfiltered and unabridged, exhaustive and exhausting. His 1997 memoir, Crazy from the Heat, is a jewel of the trashy-bio genre — most of the book is the stuff you'd dog-ear in other trashy bios — but that will soon be a cocktail-napkin scribble by comparison. At a half hour, guest-free, every three weeks, his pace is ferocious. The shows do fine; the podcast is regularly in the iTunes top 200, and each episode has around 20,000 views on YouTube.

But Roth is envisioning bigger things. He is only starting to sift through and digitize and catalogue a dozen or so hours of no doubt incriminating video and Super 8 footage he shot backstage and on the road during Van Halen's bacchanalian prime that can serve as the springboard for future episodes. (There has never been an authorized Van Halen documentary; he's taken it upon himself to be the band's de facto archivist.) He seems no less consumed with chronicling himself than a teenage livestreamer, and not just for the benefit of fans he has in the bag.

"If I narrate this appropriately, I can illuminate," he says. "Partying means something very different now than it did back then, and there are relatively few individuals in my position who are both willing to discuss it and articulate enough to make it accessible. Do you want a Victorian-style painting with your foot up on the buffalo and a teak wood settee in front of a tent — 'Yes, wonderful hunting foray, can't wait to return home, cheeksie' — or do you want a no-holds-barred truth-told-at-every-juncture reiteration that compels questions? If your only question as a 20-year-old is, 'How did you become a success?' a fair amount of explanation is in The Roth Show." Beyond it being an erudite scrapbook of bad behavior, he wants the show to be a travelogue. He wants guests. He wants sponsors.

"You can't just go into a sumo stable and get an interview," he says — he's in pitch mode now, which does not sound markedly different than any of his other modes save for a slight uptick in urgency. "We have an opportunity to talk to a marvelous group of people that few others have access to. I'm pretty conversant on a lot of subjects, and I'm good at asking the questions."

It doesn't even matter much whether the stories are apocryphal. The legend that Van Halen wouldn't play if they found brown M&Ms in their backstage jar is cited as a prime example of the era's excess and hubris; the reality is that the request was buried in their contract rider as a test to see whether venues were abiding by the intricate technical specifications for the stage and sound — at first blush, that's more boring, but as a whole, it's a proper snapshot of frontier life. By now these legends add up to a bigger story that is true, even if it's not all, you know, true.

There are no lights, not in here, not in many of the rooms; at night in the office, Roth uses the TV for illumination, and beyond that, he's got 25 years of walking in the dark here, he knows every corner, there's not much to bump into. When it gets too dark to see across the desk, he calls downstairs to Mark Rojas, who was a kid when his mother worked for Roth and now shoots The Roth Show. Rojas enters wearing a wool overcoat — it's downright cold now — and holding a flashlight and a floor lamp. He plugs in the lamp, turns it on, and exits.

Even a casual music fan might feel intimately familiar with Eddie Van Halen's recent medical chart: oral cancer, hip replacement. Meanwhile, David Lee Roth has been quietly paying the price for a lifetime of hard landings. He's undergone two major lower back surgeries in recent years. The office chair is missing its right armrest — Roth also had his shoulder reattached in four places and needed to be able to sleep in the chair when it was too uncomfortable to lie on his back. "See that?" He points to a framed picture of Elvis Presley mounted on the wall just a foot or two off the floor, between two open French windows. "I had to move that down because I slept with my head against that wall. Dog is here, dog watches door."

But Roth doesn't seem fragile — he barely has crow's-feet — and he's inspired and challenged by technology and youth culture in ways that he thinks a lot of his peers aren't, downloading house mixes from Beatport, hailing David Guetta and Skrillex and Deadmau5 ("I'm always curious as to who's got the biggest boom in the room"), marveling at the stagecraft of J-pop boy-band Exile. He can barely name a younger rock band that interests him or that he thinks may bear traces of Van Halen's spiritual DNA. Maybe Kings of Leon.

And he's not afraid of the contentiousness of the internet, built to destroy, or at least to embarrass — very different from the unconditional adoration from a hockey arena full of paying fans shouting along to "Panama" in unison. A few years ago, someone posted an isolated vocal track of Roth singing "Dance the Night Away" in the studio, maybe not quite pitch-perfect. "People like to feel superior to someone who's famous," he says with a shrug. "If that had happened in the '80s and was sent out to radio, that would have been a problem. But taken in the main, one lousy vocal take on the internet next to hundreds of non-lousy ones, that just describes a human being. One of the most basic definitions of art is something that compels commentary."

Even if that commentary is cruel and unbecoming and coming from entitled peanut gallerists who haven't done a fraction of what he's done in his life? "Sure," he says. "I enjoy the entitlement."

If ever there was any question that David Lee Roth was the odd man out in Van Halen, there certainly isn't now — he's the only person in Van Halen whose last name is not Van Halen. They are a band of brothers in that two of its members are brothers; in reality, though, they are partners in a highly successful corporation that operates under specific and doctrinaire bylaws, which may not be wholly satisfactory to any of the individual parties but are necessary for the continued liquidity of the firm.

Roth had never met Van Halen's current bassist Wolfgang, Eddie's 22-year-old son, until they were bandmates; they have yet to so much as step out for a coffee together, which is understandable given that he grew up knowing Roth only as that guy Daddy fucking hates. Roth fully admits that Wolfgang's involvement was never negotiable and that he hasn't spoken to original bassist and odd man out Michael Anthony in "years." "I had no choice, it was Edward's decision, but luckily for all of us, the kid is very good," he says. "If there were a lacking in the program, I wouldn't participate; I have very high standards of musical excellence. But I do feel a little like Sammy Davis Jr. in the Rat Pack."

This lack of warm fuzzies isn't scandalous, there's no friction, it's not fodder for whatever would now pass for a rock gossip mill. Roth travels alone on his own bus with Russ, the same bus that housed 13 people on his last solo tour in 2006. He sees his bandmates at the venue a little while before showtime. After the show, he goes out to a dance club or a strip club; they do not. The most shocking secret about Van Halen in 2013 is that they're not volatile or liable to collapse from the weight of interpersonal strife. The machine is built to sustain that — and in fact is fueled by the suspicion that this may not be the case.

"We don't really do anything else for a livelihood," he says, lighting another cigarette. "But what we also do is create the aura that it may never happen. Has this served us well? It's served us superbly. We're Friday Night Lights — the kid who breaks his knee and his career is ruined, the father who's drunk and doesn't show up for the important game. It may be painful, but it's better than just winning and winning. We've become one of the great American stories."

And what's more American than the institutionalization of something that once felt untamable? Van Halen's seventh album with Roth, A Different Kind of Truth, their first with him in 29 years, came out last spring. It sold around a half a million copies, which is certainly respectable by any 21st-century math. But given the tortuous backstory and the fact that the album is actually really good, or at least as good as anyone could have the nerve to hope for from a Van Halen album in 2012, the response felt fairly muted. The band didn't help matters by swearing off promotional press — of course that was interpreted as a sign of trouble, or that maybe they didn't want to talk about the fact that the album comprised reworked versions of songs that had been languishing in the vaults for as long as Van Halen has existed. ("There's so many people on television telling you why you should buy something," he says. "We felt we were making a sterling statement by not doing that.") Van Halen are playing the long con.

"What people don't suspect is that we're rehearsing, individually and as an ensemble, constantly," he says. "Year-round, stopping only for personal injury, and right now the band is doing phenomenally. But it's not like we're the Stones, living and jamming together in the South of France and getting drunk and sharing dames after we practice. It was never like that."

Barring further personal injury, Van Halen will continue as it is now: a massive box-office draw that will put out albums every few years, quite possibly featuring songs that weren't conceived in the Carter administration. There will be rumors that the band members aren't all best pals; these will be too true and too mundane to necessitate refuting, but the refuting is part of the deal, as much a part of the band's mystique as any song. What was once the Platonic ideal of rock 'n' roll indulgence is now structured around, literally, family values; for true adventure, Roth looks elsewhere. This is not a complaint, it's a fact. Without the clout and imprimatur of Van Halen, The Roth Show loses a little luster, a little marketability. Predictability is a punch worth rolling with.

"The creative process for Van Halen could be more Technicolor," he says. "Let's go somewhere French, Tahiti or the West Indies, woodshed in a studio that's on a boat, travel to little islands, and play the local bar on Wednesday and Friday nights. Somewhere that has international influence to alternately complain about and celebrate and adds more to the emotional menu than, 'We went up to Ed's place.' That mantra hasn't changed in 20 years and isn't going to. Everyone else has very real families, very real tent stakes. To me, travel is still exciting, but for others, it can smack of alienation or disenfranchisement. There are no surprises here at all. We're on that James Bond schedule, every three years."

Just as Van Halen's debut appeared smack between disco and punk, they've never been part of any movement or moment that could be considered in vogue culturally, and there isn't much that's popular now that owes them any evident stylistic debt. The Van Halen brothers had musical skills any wonky prog band would have envied, but they were more concerned with getting laid than impressing the conservatory. The played Kinks songs, but in ways that were impossible to replicate at home. They talked about chicks and cars and chicks in cars, but slyly, and with the occasional touch of Tin Pan Alley to boot. They predated — presaged, really — hair metal, yet this iteration of the band was gone by the time their blunter, glossier spawn passed for mainstream pop.

But it's difficult to parse what Van Halen means today to a generation that didn't have the poster, whose musical heroes are an @ reply away. Even with a wholly respectable new album, they exist as the cultural equivalent of a broken-in pair of jeans. Or, as Roth says, an action figure, G.I. Joe with the kung-fu grip, not meant to be updated or improved upon.

Ask Roth about his, and the band's legacy, and he'll give a good answer, as he always does, about how the band's intricate musicianship makes them impossible to imitate, by design, and how people can ape his moves or his drinking or his shirtlessness without hinting at any of his charisma, and this is all still true watching them now. But the notion of them as roughnecks or roustabouts or circus carnies is frozen in amber. If they have to be a museum piece, he'd at least like to be the tour guide.

In January of last year, Van Halen played a surprise show to announce the new album — at Café Wha?, easily the smallest venue they'd graced since the mid-'70s. "David called me and said, 'I've got great news. It's taken me 50 years, but I've finally made it,'" says Manny. "He said he wanted to pay for my trip out there, but I wouldn't let him."

Between songs, Roth did his familiar ringmaster spiel but took an especially long moment to point out Manny, front and center and beaming in this club the size of the Garden's security barrier. He reminisced about watching his uncle lay down the club's marble floor, about how being in this room made him the kind of person who could front a band way too big to be playing this room. From someone once considered to be the poster boy for rock artifice, it was about as human a moment as you'd ever need to see onstage.

"I'm ready to do it all over again," Manny tells me 15 months later. Roth is worried about his uncle — he's been having respiratory problems, but he sounds strong now, he is in pitch mode. "I have TV connections, I have friends in New York I've stayed in touch with. It would be much bigger than opening a club. I'm back in the game now." He is a lifer, and lifers don't retire. It seems safe to say that this, too, has been learned by osmosis.

It's nearly midnight. Roth and I walk to the top of the stairs and Russ saunters over, tail wagging. He asks me if I want to hear Russ sing. I do, of course, because Russ is a dog. "How about some Motown?" Roth inhales deeply and lets loose in a familiar rasp. "Daaaaaancing in the streeeee —" and then Russ joins in with, "Awooooooooooo!"

Roth cracks up like they've never done this before, but of course they have. Just because they've done it before doesn't mean it's not entertaining.