In a back room at University College London there are 37 heads in boxes. For years no one knew who they were.

They're mostly death masks – plaster casts of the deceased kept as mementos or references for a portrait, etc. – but some were made while the person was still alive. You can tell if someone was dead when the cast was taken by how sunken the eyes are, how gaping the mouth is, or how much eyebrow remains in the plaster after it was pulled off the person's face (more hairs = more likely dead, because a live person would complain a bit). Some are hollow, some aren't. One of them is Napoleon; one has a tag around his neck that reads "MURDERER – DECAPITATED 1840".

But, like, why are they here and who are these people?

The plaster heads originally belonged to phrenologist Robert Noel, who collected them between 1837 and 1850.

He wanted to illustrate a range of people and what their heads were like: poets and murderers, professors and highwaymen, child prodigies and medics. Most of them he bought from Germany and others he made himself, including one from a post-execution exhumation with the help of the local churchwarden. Ethically dubious, sure, but it was all in the name of (bogus) science.

Phrenology, the theory that the lumps and bumps on your head were indicative of intellect and personality, originated with a 19th-century German physician called Franz Joseph Gall. When he dissected bodies he noticed that the nerve system didn't end in one area of the brain – it branched throughout, forming the basis of his theory that different parts of the brain control different parts of your character. For example, if you had a prominent lump around the area of Gall designated as "benevolence", you'd be expected to exhibit benevolent behaviour. If you had a bigger bump around the area of "destructiveness", you were probably going to be more of a hot mess than someone who didn't.

Gall lectured on his research, but it wasn't generally well-received by the medical community. He did make a few loyal disciples, however, who spread the idea to the UK and France, and finally to America, where it became a sideshow attraction. You could pay to have your head read, just like you can pay to have your palm read now. At its peak in the 1820s-1840s, employers could demand a character reference from a local phrenologist who could tell them if you were going to be honest and hard-working. According to this History of Phrenology website, "the ignorant and gullible were particularly susceptible to the pretensions of phrenologists".

Your eccentric aunt would be into phrenology.

But the phrenologists treated it like a real science. They researched and recorded (some of) their findings.

Just like bad journalists and people who are infuriating to argue with, Noel and his phrenologist mates only made a big deal about things that supported their hypothesis and ignored stuff that disproved their own theories. If someone who was a known bastard had a prominent bump around the area of benevolence, it would be dwarfed by some other bump that confirmed Noel's personal view.

Noel's collection came to the university in 1912, a gift from the Countess of Lovelace (wife of the Count of Lovelace, son of Ada Lovelace).

There used to be more heads – about 47, including a bunch of skulls – but when you lend stuff to an art school things tend to go missing.

In the 1990s they were thrown in a skip but fished back out by a member of staff who liked them and gave them to UCL Museums to look after – chipped ears, severed necks, and all.

Until last year, these heads sat in boxes in a back room of the university, and no one knew what to do with them. Then some students did some digging at the British Library and found Notes Biographical and Phrenological Illustrating a Collection of Casts by Robert R. Noel, published in 1883.

These are some of the people in the boxes. And this is what the bumps on their heads supposedly mean. They fall into two categories: Intellectual, or Criminals and Suicides (this pairing alone says loads in terms of attitudes towards mental health at the time).

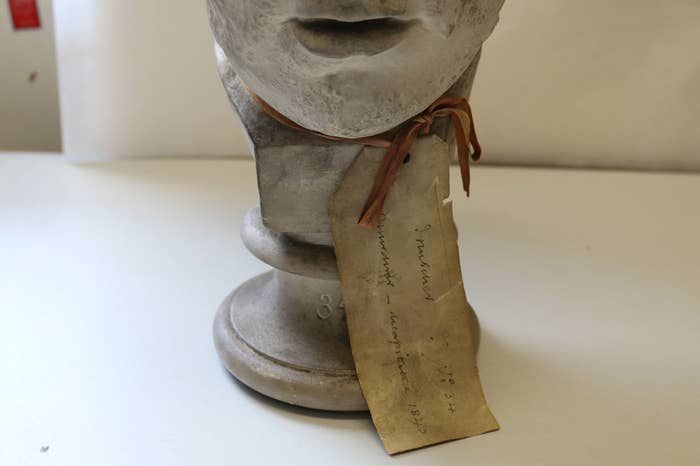

Carl Gottlob Irmscher, Criminals and Suicides. Murdered his wife and child, executed by decapitation.

The story goes like this: His wife kept her massive debts a secret from him prior to their marriage, and she accused him, "despite his ugliness" (Noel's words), of being unfaithful. All of the tension and hatred eventually culminated in him drowning their sickly son and killing his wife with an axe at the bottom of the stairs. He told everyone else in the house that she fell, but no one believed she fell repeatedly on an axe.

According to Noel's diagnosis of his bumpy head, Irmscher had a tendency to be proud, overbearing, and malicious.

Wohllebe, Criminals and Suicides. Executed for murder in Bohemia.

With the exception of this fact, we have no solid account of the guy apart from what Noel thought he could read from his decapitated head:

"The cast of Wohllebe's head, like the heads of the great criminals, displays a very unfavourable development. It is low and wide, and of extraordinary size behind the ears. The cerebellum and the lateral parts just above that organ are likewise remarkably large. The head does not show a deficiency of intelligence, but the moral faculties are wanting in development."

Johann Hatschwanz, Criminals and Suicides. Executed for the murder of his wife by arsenic poisoning.

Hatschwanz was having an affair with a married woman he had hoped to marry himself in 1850, after he had murdered his own wife and she had murdered her husband (she didn't end up doing it, but he tried to convince her to).

According to Noel, the man was an egotist. The area devoted to a love of children and animals was disproportionately small, and while his intellectual region was normal in size, his higher reflective faculties weren't as prominent as they should be. "A man with such a cerebral organisation cannot have felt the influence of love for his child and regard for its welfare as a check to vicious indulgence of his amative propensity. Neither is Caution large enough to restrain it."

TL;DR: This man fancied his new girlfriend so much that he couldn't think straight.

Christian Gottlieb Meyer, Criminals and Suicides. Murdered his children, died in prison.

This is one of those cases where Noel fudged his own science to be sympathetic. According to his notes, nothing about Mayer's head displays criminal tendencies: It shows a man of ordinary character and capabilities, with no tendency to violence. But despite the region for "love of children" being extremely prominent, he threw his own three kids down a mineshaft. A family breakdown and growing alcoholism led his children to be taken from him and institutionalised – he figured they would be better in heaven.

Says Noel: "Children have been destroyed by a parent, not owing to any innate cruelty of disposition, but simply because, when reduced to straits, their love for them has been so great, they have hoped to transport them to a better world."

After Noel visited him in prison, he was struck by the "amiable and melancholy expression of his face", he writes.

Johanne Rehn, Criminals and Suicides. Murdered her daughter, executed by decapitation.

Rehn murdered her child because she didn't want her new love interest, a soldier, to know she had one. She threw her daughter into a cesspit headfirst, and autopsy reports show that she didn't die on impact but suffocated in the filth instead.

Says Noel: "This head undoubtedly belongs to the criminal type. The frontal region is small compared with the development of the hinder part of the crown of the head. Not only is benevolence relatively deficient, but this is likewise the case as regards the seat for the faculty of love of children."

When she was beheaded, on 11 September 1852, she had to be carried up to the scaffold and placed on a chair. By this point in the day, the executioner had beheaded 25 murderers in front of 20,000 spectators. He "missed" twice before the third swing successfully decapitated her. You can see the two wounds from the first attempts, sewn up just before the death mask was cast.

Babinsky, Criminals and Suicides Category. Robbed from the rich, gave to the poor.

This cast was taken from life, in Prague, in about 1845. Babinksy was notorious in Bohemia as the chief of a band of highwaymen. He wasn't violent but kind, and only robbed the rich to give to the poor. Being a Robin Hood character, there are actual folk songs about him and you can hear one here.

Noel says his head shows no prominent features related to the criminal type: "He seems to have had imperfect notions of right and wrong, and to have acted more from erroneous views of society than from any innate tendency to wickedness."

He was imprisoned for several years, but his behaviour in prison was so good that he made friends with the chaplain and had his sentence diminished. When Noel last heard from him, he had become a gardener at one of the monasteries in Prague.

Josef Schrœder, Criminals and Suicides Category. Hanged for murder in 1843.

Schrœder had been a soldier for seven years when he falsely stated to a non-commissioned officer that he had once murdered a girl. (Why? No idea.) He was punished with 30 blows of a stick.

Three years later he deserted, taking some of the regiment's money with him. His punishment was to run the gauntlet, which is when a soldier is forced to walk up and down an alley nine times with 300 soldiers on either side, armed with sticks for hitting. If soldiers don't hit hard enough they end up being punished too.

Schrœder went through this punishment several times before shooting one of the corporals of his company and finally being condemned to death.

Says Noel: "In contemplating the head of this man, the most striking thing is that it does not belong to the criminal type." He says that anyone subjected to this kind of punishment would not come out at the other end as a good soldier, let alone a good man. He says he did not have many talents, could not be trusted, and had become "thoroughly degraded in his own eyes and in those of his comrades".

There's a clear distortion around his neck from where he was hanged.

Thomas Horlock Bastard, Esq., Intellectual Category. Built a school for shopkeepers and labourers that no one attended because cigarettes > books.

Mr Bastard (real name, swear it) was born in 1798 and this cast was taken from life in about 1839.

Despite his name, Mr Bastard sounds like a great guy. He had liberal views and built a home in England with a reading room to promote education for shopkeepers and labourers, of either sex. Apparently it was a failure because he didn't allow smoking in the room, so no one came.

"This is a head of a man of a very upright, benevolent, consistent, and self-reliant character," writes Noel. "A well-balanced head, no one faculty being greatly in excess of others. The intellectual region is well-developed, and so is the moral, benevolence being very prominent. Equally so is self-esteem."

Dr Johann Paul von Falkenstein, Intellectual Category. Lawyer and politician, went mad and ended up in a lunatic asylum.

Falkenstein was a lawyer and politician whom Noel met in 1833. According to Noel, "his knowledge of literature and modern languages [was] extensive, and ... he was amiable, lively, and extremely fluent in conversation. He did not appear to me to be gifted with originality or profundity of judgement." Backing up stuff that was already clear in life, Noel says his skull lumps were most prominent in the areas of faculty of language, capacity for attainment of knowledge, benevolence, self-esteem and "love of approbation".

He was alive and well when the cast was taken, but 12 years afterwards he was in an "idiotic state in the lunatic asylum in Pirna". His Wikipedia entry doesn't mention that.

Dr August Friedrich Günther, Intellectual Category. Introduced Noel to a man with lots of skulls, kept his own wife's skull after she died.

Soon after arriving in Dresden in 1833, Noel met this guy, who in turn introduced him to a man called Dr Seiler with a large collection of skulls. Seiler laid out 30 skulls on a table and asked Noel to examine them to see if he found anything notable about them. From the 30, Noel picked out five murderers, and was somehow correct. He obviously used this fact to back up his science at several later dates.

As for Günther's head, Noel says the most prominent characteristics were benevolence, love for children, and destructiveness. When Günther's wife died he had her buried without her skull, which he had cut off and preserved. He gave Noel a copy of it, but it's no longer in the collection.

He died in 1871, and this cast was taken from life in 1839.

Karl August Böttiger, Intellectual Category. Director of a museum, ate lots of dinners with Noel.

This guy was the director of the Museum of Antiques in Dresden and introduced Greek vase painting to Germany. Noel met him in autumn 1833 (the mask was taken after his death in 1853). Even if Böttiger asked him to dinner on a day when he already had a dinner date, Noel would go anyway and pretend he was still hungry. Two dinners.

According to Noel, his head was the average size for educated Germans, and he was a man of "considerable intellectual capacity, and of an amiable, sociable disposition – not a head common with religious and moral people or of the lower and hard-working classes."

Apparently the faculty for language appears less prominently than it did while Böttiger was living because the eyes collapse after death.

Dr Graves, Intellectual Category. Discovered Graves' disease, saved loads of lives on a ship.

This is the same distinguished physician who gave his name to Graves' disease. He died in 1853, aged about 57, just before this cast was taken.

Noel's notes on this guy are mostly about a sea voyage to Sicily that went wrong. When the ship was struck by a storm, the sailors wanted the captain to abandon the ship and its passengers to their fate. Graves took command of the ship from the captain, and managed to get everyone to safety. Says Noel: "I have never seen a head of that size and shape, particularly when elevated at the topmost backward curve ('firmness' and 'self-esteem'), that was not connected with force and decision of character."

Julius Shönberg, Intellectual Category. Young musical genius.

Born in 1837 and died in 1842. At 9 months he was placed in front of a piano; at 2 he was already recognised for his musical talents.

This is a death mask. That's all we know.

SKULL AMNESTY:

If you went to the Slade School of Art in the '80s and took home one of Noel's skulls, Nick Booth at UCL is offering a skull amnesty. You can just return it and he will ask no questions about your drunken student antics. He says to tell you it's probably haunted and you don't want that in your house anyway. He'd like it in his office with the rest of them. He's weird that way.

MASSIVE thank you to Bryony Swain at UCL for picking her favourite heads and getting them out of their boxes.