DURANGO, Mexico — When Claudio Hugo Gallardo disappeared in 2013, his sons scoured the local hospital, prison, and morgue frantically. They combed through video footage recovered from Gallardo's last known location and even inquired with the cartels whether their operatives had picked up the well-known lawyer.

But before Gallardo's family could find him, they stopped looking.

"It's for our own peace. We don't want threats," said Claudio Gallardo, one of the attorney's sons. The family has floated several theories, including the involvement of government officials, cartel thugs, and a combination of both, but prefer to be discreet about their findings, citing orders by local authorities to stop prodding.

Gallardo is one of more than 60 lawyers killed or disappeared here during a spate of crimes against litigators that began in 2008, according to members of Durango's Benito Juárez Bar Association. Some of the bodies that have been recovered carried messages from criminal groups saying the litigator should not have been defending certain clients, said Celina López Carrera, who is in charge of the state's public prosecutors.

The Durango attorney general's office opened a specialized unit to investigate crimes against lawyers in 2010. The unit's head, Orieta Valles, said none of the 14 cases assigned to it have been solved.

Lawyers in Durango operate in one of the most hostile environments in the country, in the heart of Mexico's Golden Triangle — the marijuana and poppy-growing region straddling Durango, Sinaloa, and Chihuahua states. For as long as local residents can remember, Durango has lived under the grip of the powerful Sinaloa cartel, led until recently by Joaquín Guzmán Loera, known as "El Chapo," Mexico's most wanted drug kingpin. Guzmán was arrested last year, more than a decade after escaping from a high-security prison.

The area was especially battered by violence after former President Felipe Calderón launched his war on organized crime in 2006, fracturing the large, traditional syndicates into smaller, more volatile ones. By 2010, the three states forming the triangle placed in the top five most violent in the country, according to a study on criminal trends by México Evalúa, a public policy research group.

A semblance of calm has since returned to the city, 194 miles northeast of Mazatlán, a popular destination for U.S. and Canadian retirees, with the homicide rate on the decline. But the repercussions of years of drug-war-related terror are evident, having transformed not only the lives of litigators' relatives but also the willingness of lawyers to take on certain cases.

What happens when people go missing and those left behind do not have the minimum measure of protection to speak up and demand an investigation? And what happens when the missing are the very people tasked with upholding justice?

Rosa Maria Reyes, Gallardo's wife, can't help peering out the floor-to-ceiling window in her living room every time a car stops outside the house. "One day he will arrive in an unknown car and he'll ring the doorbell because he doesn't have keys anymore," Reyes said. "Maybe I'll be angry at first, because he left me for a year, seven months, and one day."

Reyes's two-story, impeccably neat and cozy house is dotted with photographs of the family — Gallardo and Reyes dressed as Shrek and Fiona for his 50th birthday, the couple posing ceremoniously on their wedding day in a yellowing image, their sons beaming alongside their perfectly coiffed parents in another.

"We were supposed to grow old together," said Reyes, her fine features tensing up. Reyes says she was a happy housewife before her husband disappeared. Now she makes and sells tubs of strained yogurt and works at a stationery shop to ensure an income.

Claudio, her middle son, says he has made peace with his father's fate, but Reyes still dreams of packing her bags and leaving Durango with her husband when he returns. She keeps Gallardo's files stacked up in the patio, gathering dust, for when he does. In the meantime, a series of questions — who, why, how — runs on loop in her mind, starting anew with every waking minute, rendering her an exhausted shell of a person at the end of the day.

Forced disappearances have been on the rise in Mexico for years, but the recent case of 43 students who went missing in Guerrero state sent thousands of frustrated, violence-weary citizens to the street and forced President Enrique Peña Nieto to address the issue of security despite his efforts to center attention on the economy and his signature series of constitutional overhauls.

Earlier this month, on Feb. 2, parents of the missing students traveled to the United Nations in Geneva to appeal for help in finding their sons, explaining that they did not trust the government to do so. Shortly after the visit, the U.N. Committee on Enforced Disappearances concluded: "The grave case of the 43 students that were forcibly disappeared in September 2014 in Guerrero illustrate the serious challenges the State is facing in terms of prevention, investigation and punishment for enforced disappearances and the search for missing persons."

But some in Durango whose loved ones are among the 23,689 people currently on the national missing persons registry say they feel that their plight has gone entirely unnoticed by both the government and society. Unlike the families of the 43 disappeared students, there has been no cohesion among the relatives of the missing or murdered lawyers, forcing each to deal with their despair in isolation.

Sara, who asked that her real name be withheld for fear that speaking out will jeopardize her government job, has shared the pain and uncertainty of her husband's disappearance only with her two young sons. She felt socially ostracized almost immediately after her husband, a lawyer, went missing in 2008 — her family treated her awkwardly, hurrying to fill the empty seat next to her at social gatherings, their expressions filled with pity.

As is often the case when someone disappears in Mexico, potential suitors suspected her husband might have been involved with criminals and wondered if she was as well. But Sara, too, had trouble trusting the people around her and constantly wondered if any of them had been involved in her husband's disappearance.

To keep paying the bills, she sold her jewelry and one of the family's cars, cut back on luxuries like a full-time maid, and started bringing back goods to resell during her trips to the United States. Sara, an articulate, warm woman who exudes emotional strength despite her eyes filling with tears when talking about her husband, considered pulling her sons out of private school before the director offered them scholarships.

Perhaps the hardest part, she said, was the legal limbo she found herself in with no one to counsel her on how to overcome the challenges it presented. With her husband neither dead nor present, Sara could not stop his debts from running, get insurance money, or renew her sons' passports. Neither could she move forward emotionally.

Shortly after her husband went missing, Sara, who was in therapy until recently, sat her sons down and told them that they needed to assume their father had died and start grieving before they were irreparably worn down by the waiting, wondering, and worrying. They spent "the hardest day of their lives" hugging their patriarch's shoes, caressing his cereal boxes, and listening to his favorite music.

The three sometimes still argue about whose pain is bigger and whose loss is more irreplaceable, but the experience has made them unbreakable, says Sara, who works hard to make sure her children do not grow up harboring resentment and anger toward their father, for leaving, and the authorities, for participating in his disappearance.

When a friend called to tell her that human remains had been discovered nearby about a year after her husband disappeared, Sara thought about collecting a set. "It may not be him," says Sara, but they would afford her the luxury of getting a death certificate and formalizing her family's grieving process.

She took the remains home.

A number of clandestine grave sites have been discovered in the middle of Durango city, a warning sign for the 600,000 residents who lower their voices when they talk about the criminal groups that operate in the city, referring to them only as "those."

BuzzFeed News requested a list of mass graves discovered in the state since 2006, but the state's transparency unit responded that the information was confidential. According to CNN, more than 330 bodies were discovered in grave sites in Durango between April 2011 and February 2012. The remains of two lawyers have been discovered in such graves, according to Lopez Carrera, the official in charge of the state's public prosecutors.

Many lawyers are heeding the warning that the graves perhaps sought to send. According to sources who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals, including a government official and a person with knowledge of judicial matters, some ask for permission from "third parties" — members of the dominant cartel — to take on certain cases, abiding by an unofficial roster of which people can be defended and which cannot.

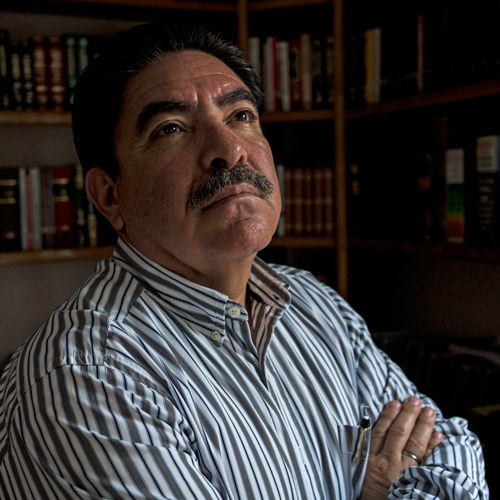

A few, like José Isaías Silerio, president of Durango's Benito Juárez Bar Association, have shifted the bulk of their practice from criminal to civil cases in an effort to prevent contact with potentially unsavory characters, focusing instead on mercantile, family, and labor law.

"It's not about how much money a case will bring me but about what kind of trouble I'm going to get into," said Silerio, whose brother practiced law and was killed in 2009. Whenever he gets calls from new, potential clients, Silerio says he talks to God directly: "Enlighten me, tell me which cases are ugly."

Valles, head of Durango's Specialized Unit for Crimes Against Lawyers, told BuzzFeed News that the unit has "not had a lot of cases, but they were high impact," speaking about the 14 cases assigned to her. Still, she admitted that "lawyers are more careful. They are frightened." The biggest challenge, she added, is that relatives of victimized lawyers are not willing to help her team investigate since they are afraid they will get in trouble with whoever took their loved ones, which some suspect is a combination between cartels and authorities with overlapping interests.

That holds true for Reyes, whose daily search for her husband ends where her driveway begins. Her nephew, who had contacts at the state attorney general's office, told her to stop investigating. She did, afraid of angering those who snatched her life-long companion away, catalyzing another tragedy and destroying what is left of her family. In any case, says Reyes, authorities never asked her to testify, gave her an update on the investigation, or offered her any support.

Her son, who initially believed the authorities would help him, gathered documents and security footage from the convenience store where Gallardo was last seen and gave authorities a blood sample. It led nowhere. "I put together the investigation so that it could become another number," the 29-year-old said.

Sara, who suspects authorities were involved in her husband's disappearance, did not want to file a complaint, thinking it a waste of time from the beginning. "I knew what farce I would be involved in," she said, adding that she feared demanding an investigation would cost her her job at a moment when she needed it the most.

With lawyers taking on only "approved" cases, some people needing legal counsel are struggling to find it.

Víctor Cordero Giorgana was arrested along with 150 other public officials in 2013, when he was chief of police for the municipality of Gómez Palacio, a city in Durango state, and charged with homicide, kidnapping, and organized crime. Giorgana said he was beaten and forced to sign a confession he could not read. His family hired him a lawyer.

After the lawyer went to a courthouse to pick up his client's file, several men instructed him to get into a van, according to Erick Cordero Giorgana, the former chief of police's brother. The men kept the file and the lawyer quit shortly after.

Since then, Erick, who lives in Alaska, has been unable to find a lawyer to represent his brother in Durango, and he cannot afford one from outside the state. The former chief of police remains in prison.

Silerio understands the forces that may be keeping lawyers away from cases like Cordero Giorgana's. A self-declared temerarious man, he says the years of bloodshed in the state taught him to stand down. "If I wasn't afraid, I wouldn't be alive," said Silerio.