Rihanna’s wins come in stunning, rapid succession. Just a few days after the March 26 release of her latest single, "Bitch Better Have My Money," she enjoyed another success: Home, the animated DreamWorks film for which she voices the adorable protagonist, had an impressive $54 million opening weekend. To be 2015 Rihanna is to twerk on top of the world and know you climbed your way there with the odds (and the cash) stacked against you.

“Don’t act like you forgot / I call the shots, shots, shots,” she sings on “Bitch Better Have My Money.” Amid throaty snarls, Rihanna flashes the spoils of her fame; she sounds confident, assertive, and undeniably powerful, the inheritor of a legacy built by black female artists who make carefree magic in the margins of society and the music industry alike. She is the waist-whinin’, finger-flippin’ daughter of Kelis, Erykah Badu, Trina, and so many other black women who take no bullshit as they insist on taking up space. Kelis pioneered some of the illest Weird Black Girl aesthetics for which the aughts were famed, and taught us all “Bossy” doesn’t have to be a bad word (sorry, Sheryl Sandberg). Erykah Badu is too ethereal to be pinned down. Trina is, was, and always will be Da Baddest Bitch. What unites these trill-ass black women across time and genre is the insistence on staying in — and dominating— their own lanes, with the confidence to disregard anyone who questions their place in the driver’s seat (or how much fun they’re having with the music blaring through their speakers as they cruise). They celebrate their art, themselves, and one another on their own terms, navigating the perilous waters of visibility largely by rejecting the onerous respectability demanded of black women. In a world that tells black women we have no right to authentic joy and no purpose in the music industry beyond an ornamental backdrop for male brilliance and bravado alike, their deft maneuvering is a choreography of resistance.

If 2014 saw the meteoric rise of the Carefree Black Girl trope, then Rihanna was the island wind beneath its weave. The 2014 Carefree Black Girl lined her pockets with her predecessors’ whimsical self-determination, a kind of revolutionary lightness that writer Jamala Johns describes as “the freedom and exuberance of simple moments and pleasures: clutching flowers, enjoying the company of your equally stylish friends, reveling in creative endeavors, and even finding the ethereal beauty in not-so-carefree moments. Admittedly, it feels weird to describe scenes that, for some people, may seem mundane or even cliché. But, for women of color, such basic depictions continue to go underrepresented.”

RiRi crafts notably rebellious black female self-determination in this spirit, eschewing propriety in favor of a carefree, self-indulgent womanhood not contingent on respectability. She demands authority over her own body, narrative, and career. The video for 2013's “Pour It Up” features Rihanna making it rain both by and on herself. The dollars themselves have her face on them, the perfect currency for her autoerotic fantasies. The effects of her refusal to shrink into the constraining molds handed to her — the “acceptable” ways to perform wealth, womanhood, blackness, and victimhood — ripple beyond her work and her fanbase. Rihanna’s defiant ascent to superstardom offers glimpses into a world where all black women can revel in (or rebuff) the limelight on our own terms and laugh while doing it, where our creativity, beauty, and worth are not graded against the impossible sliding-scale rubric of white femininity.

If Beyoncé and Nicki Minaj are two meticulously constructed, divergent brands of black womanhood, then Rihanna is the renegade blurring of the lines between them. Beyoncé is a poised, almost mechanical demigoddess; Nicki is an ineffable, ferocious femme fatale. Rihanna exists in the sharp gray areas between them, carving a space all her own. Her trajectory from “West Indian Beyoncé” to electro-R&B princess to pop queen (regardless of her sometimes questionable vocals) has zigzagged in nonlinear ways that neither Beyoncé’s nor Nicki’s has — because neither Beyoncé nor Nicki has the option of expanding her lane in the way Rihanna has been able to constantly modify her brand. The appeal of Rihanna’s persona lies partly in its constant evolution, in her refusal to be called the “new” anybody.

But no matter how many multitudes any black girl contains, she still operates in a world that categorizes and constructs her identity before she has the chance to assert it. Celebrity status notwithstanding, Rihanna must contend with a social climate rife with both misogyny and antiblack racism. This is the world in which Rihanna makes demands of those around her, where she stares modalities of the genteel in the face as she stomps on them in shiny new Louboutin stilettos. “Bitch Better Have My Money” is the sonic crystallization of her counterculture insistence on being paid her due, as critic Doreen St. Félix writes at Pitchfork: “The black girl flaunting money is ratchet, the black girl with money bankrolled her way there through sex, therefore the black girl with money does not properly own it. Since the racist and the sexist are also by definition prudes, this black girl of their fantasy, no matter how tall her money, can never signify wealth, a sort of class ascendance that has as much to do with politesse in gender roles as it does one’s stock profile.”

Indeed, when (post)colonial imaginations of gendered and classed wealth reject black women as eligible citizenry, the repercussions are read onto our bodies themselves. Rihanna’s sexuality, like that of all black women regardless of celebrity, is regularly policed. When she appears anywhere in an outfit not appropriate for a Catholic mass, writers and parents and Twitter-dwellers rush to remind her she really ought to be wearing more. “Dear Rihanna, you’ve gone a little too far with this ‘outfit,’” @Celebuzz tweeted when she had the nerve to wear a crocheted white skirt with a bandeau top. “May be time to class it up and put some clothes on?” These judgments are steeped in a long history of deeming black women’s bodies perpetually hypersexual, the same history that informs uproar about Beyoncé’s “whore”-ish performances and the Obama daughters’ “class”-less clothing. Girls and women whose bodies carry blackness as a backdrop must apologize for the eroticism permanently read onto us. But Rihanna doesn’t beg pardon for her body; she claps back. She responded to Celebuzz the same day with this nail-polish-emoji-worthy retort: “your pussy is way too dry to be riding my dick like this,” a clever weaponizing of the same sexuality Celebuzz attempted to shame her for.

Rihanna boldly insists that her body is her own. As a spectator, you cannot and will not dictate what she does with it — whether she wears a Carnival outfit from her native Barbados, a marijuana-leaf-emblazoned jersey, or nothing at all. Rihanna runs the show, and her commitment to uncompromising bodily autonomy undergirds both her public persona and the music that drives it. She sings about her BDSM proclivities on Loud’s “S&M” (2010) while subverting rigid understandings of both feminine performance and domination: Armored in pink latex in the pre-Fifty Shades of Grey video, she hits a submissive Perez Hilton with her riding crop after he urinates, crouched and doglike, on a pink fire hydrant. “I may be bad but I’m perfectly good at it,” she sings, flirting with both listeners and, more importantly, power itself. “Sex in the air, I don’t care / I love the smell of it.”

The preceding album, 2009's Rated R, may have been noted for delving into Rihanna’s post-Chris Brown internal world, but it also brought to the fore a more frank discussion of her own sexuality. “Rude Boy,” the album’s third single, became the unabashed anthem of girls who just wanna know if a dude can put it down before they bother getting in bed with him. “Come here rude boy, boy / Can you get it up?” she asked, dismissing subtlety in favor of a sexual pragmatism so often denied women. That she could do that on the same album in which she navigates the pain of her relationship with Brown is emblematic of Rihanna’s insistence on being regarded as multifaceted (or, you know, human). Rihanna’s narrative as a survivor of abuse is complicated; she refused to be a role model, sidestepping the expectation that her road to healing would be linear or neat enough for outside parties to understand. For a woman in the public eye, that kind of resolve — indeed, that kind of rebellion — is its own revolution.

But Rihanna’s interest in and insistence on her own pleasure appears throughout her music; she may be invested in her sexual partner, but his orgasms should never come at the expense of hers. “Cockiness (Love It)” is an ode to the joys of cunnilingus: “Make me your priority / There’s nothing above my pleasure” is not a lyric to be taken lightly. The song, from her 2011 album Talk That Talk, predates Beyoncé’s “Blow” and Kelly Rowland’s “Kisses Down Low” — but it’s in conversation with the work of other black female architects who pioneered the Pussy Eating Anthem genre. “Cockiness (Love It)” inherits the legacy of Khia’s legendary “My Neck My Back” (2002), Lil' Kim’s “How Many Licks” (2000), and SWV’s “Downtown” (1992), among countless others.

But for every sweated-out perm made possible by these tracks, black women artists have felt the pushback of public opinion on their (new) growth. Gendered expectations of black women’s hair are stifling, even among light-skinned artists like Rihanna, whose fairer complexions make them more palatable to white audiences. To be a black woman in industries that explicitly demand you conform to Eurocentric beauty standards is to subject your hair to endless, damaging treatments: chemical relaxers, high-temperature flat irons and hot combs, braids and weaves that can rip out fragile hair at the edges, and so much more. It’s exhausting and expensive. Scorching your hair into submission is an imperfect science.

When fellow Carefree Black Girl princess Solange cut her tresses down to a tightly cropped ‘do in 2009, she was immediately called “insane” — even after she tweeted that she ditched her locks because of the immense stress associated with their upkeep: “i. just. wanted. to. be. free. from. the. bondage. that. black. women sometimes. put. on. themselves. with. hair.” And derogatory remarks about Rihanna take aim at her tresses too. After she revealed the cover for her “Man Down” single in 2011, a fan tweeted her displeasure about the coarseness of Rihanna’s hair: “why does her hair look so nappy?” Rihanna responded simply: “cuz I’m black bitch!!!!” For Rihanna to assert that her hair is nappy because she is black — as fact, not apology — was at once comedic and powerful.

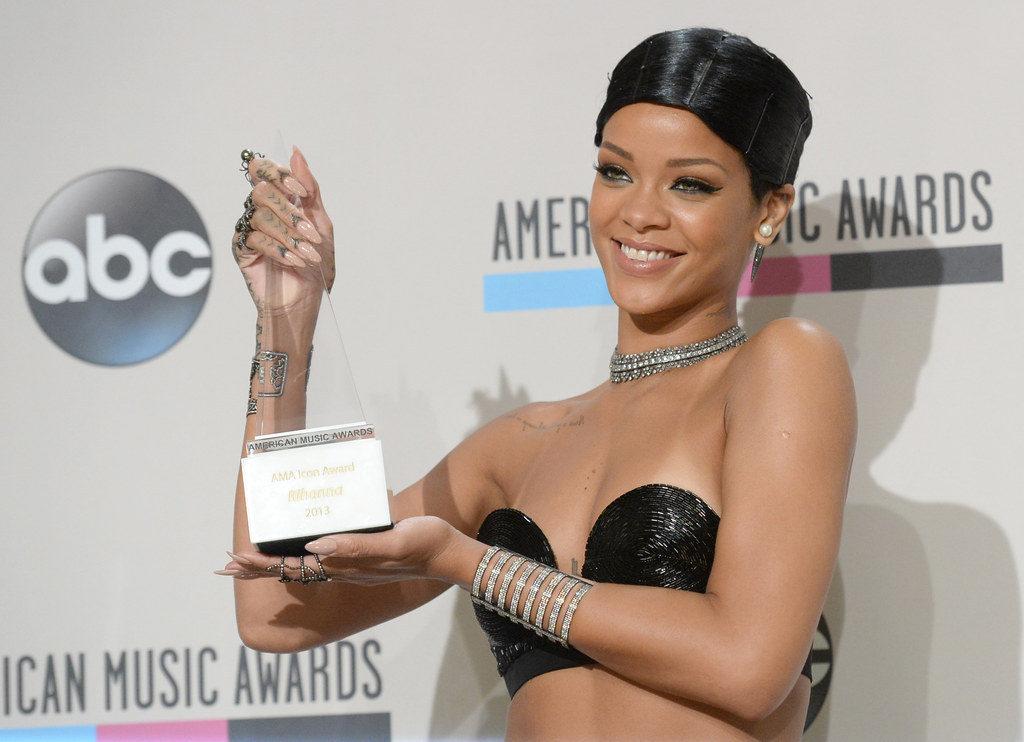

Rihanna’s defense-worthy hair is both a marker of trendsetting creativity and smirk-worthy rebellion. She has graced countless magazine covers and launched a thousand hairstylists’ careers with iconic cuts that send people flocking to salons in search of her edginess. From sharp, angular jet-black bobs to bright red, curly wigs, Rihanna’s hair demands attention. But perhaps her most carefree, mega-troll hairstyle was the one she debuted while accepting her award at the 2013 American Music Awards. In true bad gyal form, she showed up to a nationally televised red carpet event rocking a doobie wrap, the unofficial "looks like it’s just gonna be a Netflix night" uniform of black girls 'round the world.

The hairstyle, most often worn to bed, is by definition a functional preparation for the look that will follow it: Nobody rocks a doobie wrap unless they’re getting their hair ready for a “real” style. Rocking the follicular equivalent of fuzzy rabbit slippers at a red carpet soiree where she was being honored is the illest “I don’t actually wanna be here with y’all, I’m just tryna look cute for the party I’m hittin after I get that damn trophy” message she could possibly have sent. And it was made even more satisfying by the fact that most white writers didn’t understand the grammar of that fundamentally black aesthetic. Some even called it a “faux pixie crop,” and white women around the country began to replicate it, oblivious to the fact that they’d elected to copy the larval stage of her beauty troll metamorphosis.

Still, for all her dabbling in controversy, Rihanna has achieved remarkable levels of commercial success within the music industry as well as outside of it. Last month, Dior announced her as its first black “Dior Girl”; earlier in her career she was the face of Cover Girl. Her style is unparalleled, spawning blog post after magazine article after editorial spread, year after year. She has modeled alongside Naomi Campbell and Iman. Home is the first 3D film to feature a black female protagonist, the character Rihanna herself voices. She is the most-streamed female artist of all time on Spotify.

And so Rihanna reigns as trill-ass, troll-ass Carefree Black Girl of our generation. She blows marijuana smoke in reporters’ faces, sings alongside legends like Paul McCartney and Kanye West, and shmoney dances on yachts. Bad Gal RiRi has earned her place and held her own among entertainment’s greatest with style, finesse, and an incredible, far-reaching dearth of fucks to give anyone who doesn’t like how she lives her life. No black female artist gives off the “I would smoke a blunt with you in the middle of this board meeting if you gave me The Nod” vibe like Rihanna. No artist in the game, regardless of genre, race, or gender, has mastered the art of not giving a fuck so gracefully. In a world where presentation and poise are everything, Rihanna’s cat-eye rolls and red carpet doobie wraps are a breath of fresh weed smoke.

Everything she does raises the question “can I live?”— and simultaneously lets you know she decided a long time ago the only acceptable answer is yes. This is Rihanna’s world, and you better believe she calls the shots.