Raphael Cohen climbed into the ring, through the gap between the taut ropes, one leg first, before snaking his torso through and then pulling his other foot in. His cornermen, Benny Carroll and Jimmy Halloran, who worked with him shoveling coal for the engines, held him by the shoulders, as cornermen do, and they would have steered him and kneaded his shoulders and rubbed his arms.

As he entered the ring for the first round and heard the roar of the men, his secret was surely apparent — this was Cohen’s first time in an actual boxing ring, and that moment of recognition can’t be blustered. Yes, he may have fought on street corners, and sparred and brawled in the hidden corners of the warship, but this was different. The ring was enormous. It dwarfed the space where he shoveled coal, where he had worked for precisely 614 days. And he had never stood before all these men like this, as they laughed and clapped and whistled.

He must have had the nervous panic and impatience of any first-time fighter. Boxers suffer stage fright just as actors do. Too hot, then too cold. Hands clammy in the foul-smelling 5-ounce boxing gloves borrowed from another ship. And the formal minutes before a fight, the deafening clamor of the jeers and the shouts, the panic one has to bluff and swagger through, they were new to him.

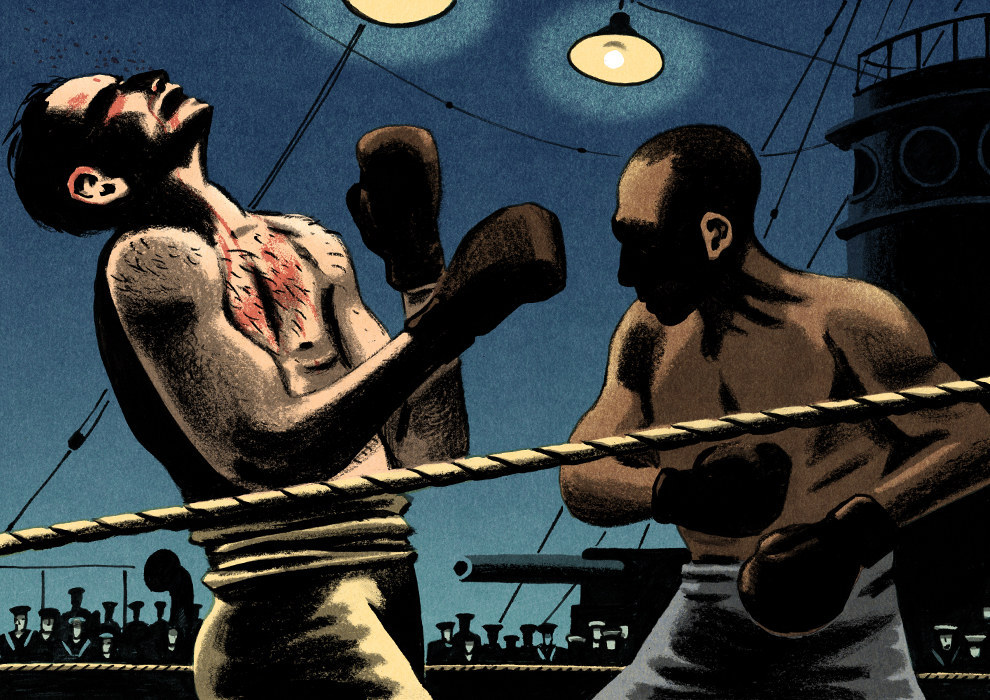

The light was dim, though the boxing ring was lit by the most advanced electric Navy deck lights of the day, 32 candlepower lamps. (A modern car headlight is 5,000 candlepower.) Diagonally across the ring, Cohen could see Jordan Johnson, a black man, calm and silent, an experienced fighter, waiting in his corner.

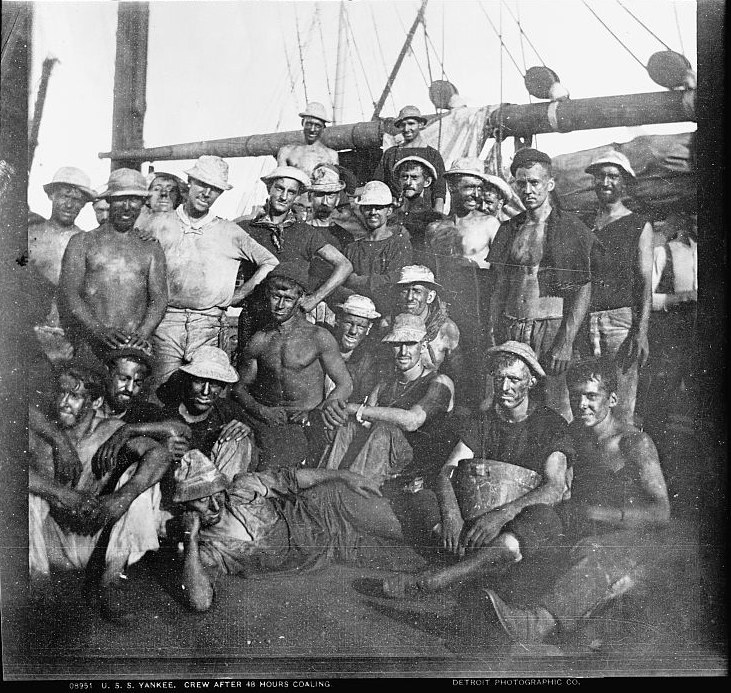

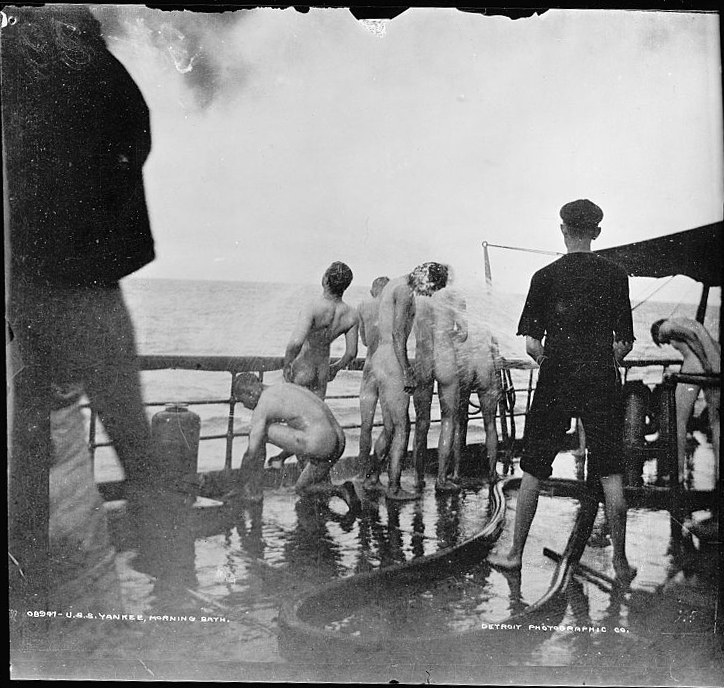

It was shortly after 9 p.m. on July 8, 1905. The captain of the USS Yankee, Edward Francis Qualtrough — 55, overweight, fond of liquor — looked down at his ship’s foredeck. He was entertaining a fellow skipper, and, watching from the bridge, he must have felt an irritating lack of control at what was happening on his own ship. In a makeshift boxing ring, a black man and a Jew, bare-chested in the Caribbean heat, were pummeling each other.

The fighters, both small and fast-moving men, sparred. Around them, the ship was crammed, virtually infested with spectators: Marines and sailors from every ship in the squadron languishing in the doldrums off the coast of the Dominican Republic. Six hundred men in uniform, standing, sitting, perched on the rigging and the rails, watching and laughing.

A spectacle like this — a chaotic boxing fight taking over the ship — wouldn’t have occurred so overtly back when Qualtrough graduated the Naval Academy in 1871, 34 years earlier. But now, with Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency and his public passion for the manly art of boxing, captains were to encourage matches aboard their ships. They were called "smokers." Of course, the irony was that this smoker, between the Jewish sailor and the black sailor, conflicted with Roosevelt’s other passion, the mythology of Anglo-Saxon Teutonic America and its place in history.

It was also clear to Captain Qualtrough from 40 yards away that the black man was the far better fighter. His name was Jordan Johnson, a gunner’s mate from the USS Olympia, and as he stood in the dim but harsh artificial light and the heat of the tropical night, he displayed the chiseled physique of a Greek god, similar to those of the bronze nude statues that Qualtrough’s wife collected, back in Washington, D.C.

Johnson also would have been one of the only black men in sight, anywhere. All those jeering faces in the crowd, visible in the dimness, though the sun had just set — nearly all those faces belonged to white men. Black men had been shunted out of the Navy under Roosevelt. Those who remained worked in the mess halls or as obsequious servants for the officer cadre; they were made virtually invisible on the decks.

For Captain Qualtrough, too, this disappearance of the black men in the fleet was new, because when he first came aboard as an ensign in 1870, black sailors were common. But now, from his perch high on the bridge, Qualtrough could have heard the crowd of sailors under his command hissing at the bare-chested young black man in the ring.

During this period, a Jew and a black man boxing on a U.S. warship would have been seen by many as objects of ridicule — performing clowns, rather than gladiators.

As for the Jewish fighter, Raphael Cohen, he was a sailor on Qualtrough’s Yankee, though the captain never met him. Cohen worked shoveling coal in the boiler room for the engine, unskilled hard labor that didn’t bring much of a promise of a future, though it did build a distinctively muscular physique. Cohen’s torso was hairy and a pale white, but his face and arms were stained black with coal dust. In fact he and the men he worked with were known as “the black gang” aboard these coal-powered warships, and his face, dark against pale lips, must have looked like a grotesque attempt at blackface. During this period when the Navy was scrubbing itself of African-Americans, a Jew and a black man boxing on a U.S. warship, no matter how they fought, would have been seen by many of the men as objects of ridicule, perceived as performing clowns, rather than gladiators.

The Yankee was deployed to the Dominican Republic not in defense of American land or liberty, but rather on a new form of gunboat diplomacy enforced under the brash President Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s project: to take over the finances of a foreign country whose crime was that it owed money to a powerful American company. It launched a new era in American military intervention — an expedition for profit, not principle.

Indeed, Roosevelt’s influence is threaded through this story: Not only did he send the fleet on its mission, but he was also an impassioned champion of boxing in the military. And whether the idea originated with him or not, he presided over the systematic removal of black Americans from Navy life.

That boxing match between a young black sailor and a Jewish sailor aboard an American warship, and the death of one of the fighters, caused a scandal 110 years ago, threatening the careers of powerful men. Newspapers across the country picked up the story, citing lurid allegations that the bout was held “for the edification” of the officers, and that the fighter who died had pleaded that he was sick and was forced to box, even after he’d been hit so hard that an artery in his brain tore, flooding his brain with blood. It was testament to a mix of grit, glory, and stupidity. Or perhaps just obstinate greed by a crew of men hoping to win a cash prize.

And the victor, who had literally grown up in the Navy, a man who had spent nights in chains in harsh discipline, who’d been handed to the military by his parents when he was only 15 years old, he was soon ushered out of the service, abandoned and destitute in a civilian world he didn’t know.

The fight, and the fighters, are long forgotten now, but the records — the ship’s logs, transcripts of military inquests, the enlistment reports — illuminate a dramatic turning point in American ethnic and military history.

Raphael Cohen was born in 1880, at 15 Suffolk St., a tenement building full of more than 50 Russian Jews who had been part of the beginning of the migration over from the old country. Tobias, Raphael’s father, had been in the first wave, arriving from Russia in 1866, via Germany, right after the Civil War, and became a successful tailor. The seven Cohen children all grew up in one of the most crowded neighborhoods on earth.

Journalist Jacob Riis, a social reformer of the era, explored the area in 1890 when Cohen was 10 years old, and in his book How the Other Half Lives Riis called the neighborhood “Jewtown.” He wrote that “the manner and dress of the people, their unmistakable physiognomy, betray their race.” “Thrift is the watchword of Jewtown,” he added, “as of its people the world over.” Riis captured the core of the American ghetto: “Life here means the hardest form of work almost from the cradle,” he wrote.

Of course it’s a place that survives now as imagined kitsch, evoked on the walls of Sammy’s Roumanian Steakhouse, and countless delis with their knishes and lox and herring. But even those foods meant something other than what they do now. “Pickles are favorite food in Jewtown,” wrote Riis. “They are filling, and keep the children from crying with hunger.” He recounts walking the streets at night, when a “dirty baby, in a single brief garment,” as he describes it, “tumbles off the lowest step, rolls over once, clutches my leg with unconscious grip, and goes to sleep on the flagstones, its curly head pillowed on my boot.”

It was a noisy neighborhood, and it evolved fast as Cohen grew up, just around the corner from the giant Beth Hamedrash Hagadol synagogue. A former Baptist church, it was transformed into a thing of the Old World by the immigrants from eastern Europe. The hulking building still stands, derelict now, after years of Hasidic prayer.

Down the street from Cohen’s building on Suffolk Street was Sach’s Café; the place was the unofficial headquarters for the radicals and atheists of the day. Emma Goldman, the fiery anarchist, held court, loud and fast in Russian and Yiddish.

Then, in 1898, when Cohen was 17, a patriotic fervor washed through the Lower East Side. Youngsters started dreaming of being soldiers. War with Spain was coming. The Hearst newspapers provided daily accounts of Spanish atrocities to the rest of America, and so did the Yiddish newspapers.

It was so over-the-top that the Commercial Advertiser in the spring of 1898 ran a story titled “Ghetto War Spirit,” with a subheading: “Jews Bear Spain an Old Grudge — Manila a Victory for Israel — ‘God Gave America the Job of Smashing Spain.’” Somehow the Spanish-American War, the reporter found, was now seen as a vehicle for vengeance against Spain for its atrocities of centuries past, for Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand’s old war against the Jews, and the crimes of the Inquisition. America — through this war — was offering its new Jewish immigrants not just the chance to remake themselves, but the chance to seek vengeance against the old, cruel Europe that had treated them so disdainfully.

A tailor quoted in the article said, “They tortured the Jews and banished them from their land and now the God of Israel is getting even with them. It is an old story, more than four hundred years old, but the High One never forgets.”

It was in this environment that, in May 1898, Cohen's father accompanied Isidore, Raphael’s older brother, to the recruiting office. Because Isidore was a minor, a witness had to sign. The recruitment document shows that the witness was Moritz Tolk, a notary, and later an alderman, who operated out of his brother’s saloon down on Canal Street, where he helped sweatshop workers get their papers.

Isidore enlisted in Troop I of the 4th Cavalry, although it is impossible to see how he could ever have ridden a horse in his life. He was sent off to Kentucky for basic training and from there he joined his unit to steam to the Philippines. In the end, he was too late to fight the Spanish, who abandoned the troublesome colony to America shortly after the U.S. invaded.

Instead of vengeance for the Jews for the atrocities of the Inquisition, the 4th Cavalry just did battle with angry Filipino rebels. U.S. troops used the “water cure” — known today as waterboarding — to get the rebel captives to talk; they sometimes killed prisoners. But while his brother fought jungle warfare in Mindenao, Raphael, back in New York, just worked as a day laborer.

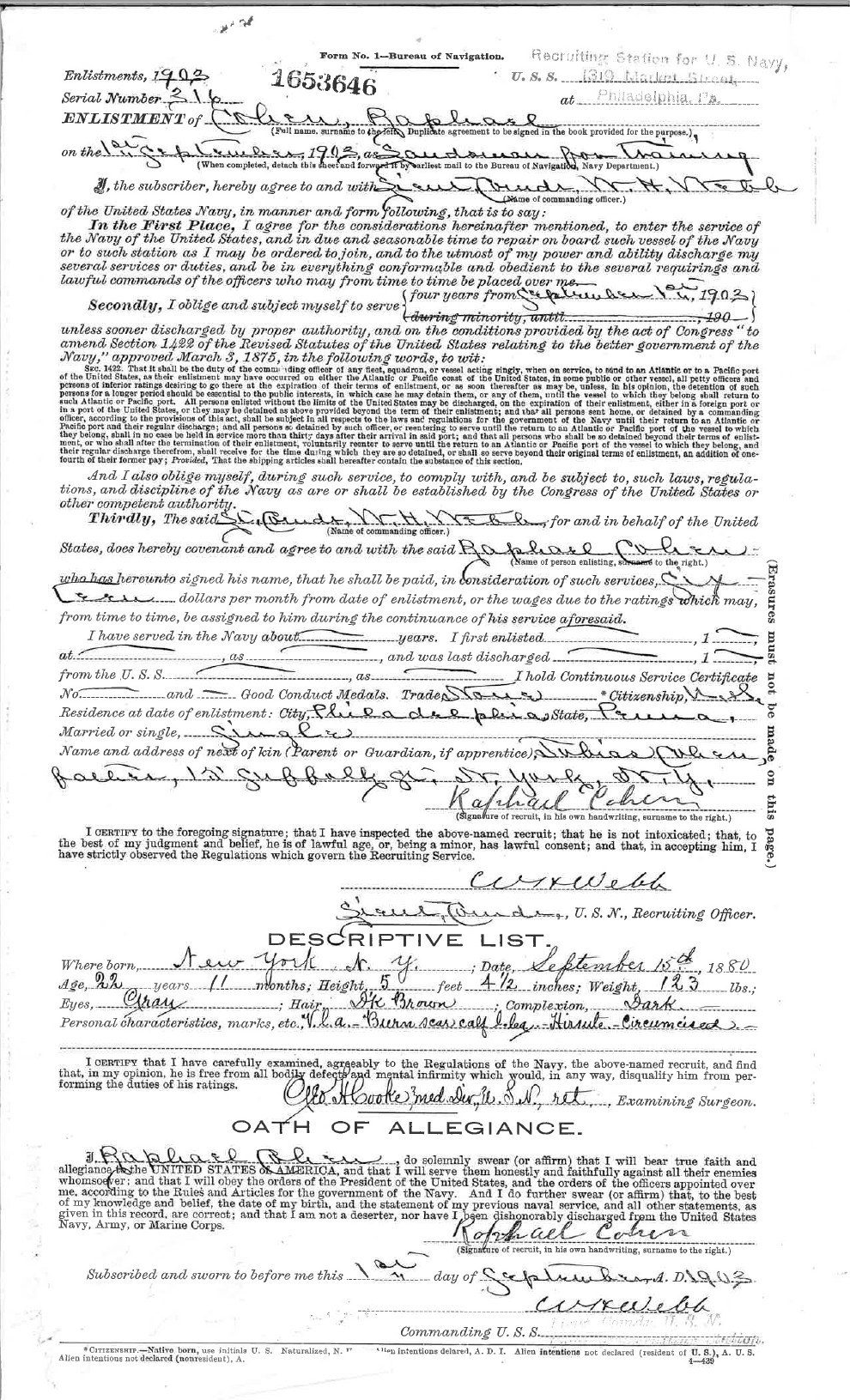

He got married in March 1903 to a girl from the neighborhood, a block away, named Sadie Shasam. The two didn’t live together for long. It’s unclear what went wrong, because the records on him go blank for some months, right after the marriage. But in September, he walked to the doors of the big Navy recruiting station down on 319 Market St. in Philadelphia. On his enlistment form, as he signed up for a four-year stint, Cohen wrote “single.”

The records show that he was given a cursory physical examination. Height 5 foot 4½ inches. Eyes brown and hair black. Weight 123 pounds. “Hirsute,” wrote the Navy surgeon who examined his hairy body, when Cohen was standing naked.

“Circumcised,” the doctor noted, too.

Just as the noise from the crowd was overpowering, in that instant, after the bell rang, was when Cohen stopped hearing it. Cohen rushed in hard and fast, with all the intensity of a spider, not necessarily boxing but bullying. He tried to buffalo Johnson into a corner with a right swing and then a left.

A zbokh, they might have said in Cohen’s old neighborhood, on the alley near Grand Street, if he landed a punch, Yiddish for a hard hit. And then a zetz. Wild swings.

But Johnson slipped both punches with ease, sidestepping with the gentle ballet steps of a fighter, and his move left him wound up like a spring to unleash a powerful left hook to Cohen’s head. A klap, as they would have said.

A sudden hammer of pain. Cohen staggered, and Johnson moved in closer with a right, then a left, and Cohen toppled to the platform.

In the end, it would have been better if Cohen had stayed down.

The fight might have ended then, after the first few seconds. Cohen was down. The crowd hissed at Johnson, who headed to the neutral corner, leaning on the ropes, and they laughed at the little Jew lying there. The referee, George Pettingill from over at the USS Detroit, began the slow count as Cohen lay groggy.

As he lay there, knocked down that first round, the bright deck lights were above Cohen, set against the night Caribbean sky and the silhouette of the bridge and the 5-inch guns. Pettingill was silhouetted there too. And Pettingill counted loud and slow. “One!” he said. “Two!” “Three!” “Four!” Five! Six!” Cohen scrambled to his feet finally.

Pettingill waved the fighters together again. They fought hard to the end of the first round, but Johnson kept Cohen heading back, retreating, and retreating.

In the end, it would have been better if Cohen had stayed down. If he had, he might have lived.

Jordan R. Johnson was born in Champaign, Illinois, in 1885. His father was from Missouri and his mother from Tennessee, and they’d followed one of the routes that freed slaves took for decades after the Civil War. Indeed, just as Jewish families like the Cohens had fled Europe for New York City, many freed slaves from the South migrated to Illinois.

At 15 years old, Johnson stood 5 feet tall and weighed less than 100 pounds. He was the oldest boy out of five children. It was 1900, two years after the Spanish-American War, the U.S. Navy was on a recruiting push in the Midwest, and Johnson, just reaching adolescence, would experience a traumatic awakening. His father handed his firstborn son over to the Navy for six years, signing a paper that rendered him “to service till he shall be twenty-one years of age.”

Though it sounds like indentured servitude, this was one of the ways the Navy built its force in the 19th century. It would sign on boys as young as 14 as “apprentices.” (In 1903 the age was boosted to 16 as a reform step.) The boys, going through puberty, would get on-the-job training aboard a crowded man o’ war, slaves to the whims of the sailors, and in theory could work themselves up to seaman first class. The money was dismal. For his work, Jordan would be paid $9 a month, though his uniform and bedding had to be deducted from that.

One can only guess how hard it was to survive for a 15-year-old black boy in a white Navy. By now, racial fights were common on U.S. Navy ships, and white sailors openly made it clear they detested black shipmates. In fact Johnson was signed over to the Navy just as the role of black men in the service was changing. African-Americans had served in the Navy for years. In the Civil War, up to a quarter of the crews aboard Navy ships were black.

By the time of the Spanish-American War and the rise of Roosevelt, things were radically shifting, and African-Americans were being deliberately dropped from the rolls. There was a tremendous irony, because just as there was a recruiting drive that would eventually double the manpower of the Navy, African-Americans were being relegated to lower positions. By 1900, “black applicants were almost as unwelcome as convicts in the modern navy,” wrote historian Frederick Harrod in Manning the Navy.

Teddy Roosevelt himself did not order all this, and it’s not really clear who did, but he certainly was there as it happened, and one can say he spurred it on, as a product of his time. He was the assistant navy secretary from 1897 to 1898, and he pushed to grow America’s vast new naval enterprise.

And Roosevelt himself would have a complicated and often dismal relationship with African-Americans, especially those in uniform. Historian Regina Akers, Ph.D., of the Naval History and Heritage Command, has pointed out that Roosevelt’s most famous military experience, his charge up San Juan Hill, was actually supported by the “Buffalo Soldiers,” a black infantry unit.

“At points during the campaign, they rescued the Rough Riders,” she said. Yet the celebrated adventurer and politician resisted embracing black soldiers. Sometimes, she said, Roosevelt gave credit to the all-black 24th infantry unit that was at San Juan Hill, and sometimes, for whatever reason, he made sure to withhold it, and imply that African-Americans were too cowardly to fight.

As president, Roosevelt was recognized for his controversial gesture of inviting Booker T. Washington into the White House for dinner. But on the other hand, his view of Anglo-Saxon Teutonic superiority was unshakable.

Roosevelt “viewed the entire breadth of the American past through a racial lens,” wrote Thomas Dyer in Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race. And the president had a constant, “almost compulsive attention to underlying racial themes.” One further clue to the way Roosevelt viewed African-Americans in uniform emerged later: In 1906 Roosevelt would be the president who unfairly dismissed 167 African-American soldiers, with dishonorable discharges, after they were unfairly accused in the case of a murder of a white barkeep in Brownsville.

Roosevelt’s influence had a dramatic impact on Johnson's life. By 1900 to 1910, “African-Americans were being actively pushed into servant roles,” as the U.S. Navy’s History and Heritage Command wrote. They were disappearing from the decks, except to play instruments and attend to the officers.

Reaching manhood in the Navy, Johnson managed to keep his sailor’s job, though records indicate that Johnson’s shipmates and commanders treated him like an animal as he grew up. One time, at 17, he had been made to sleep locked up in chains on his wrists and ankles for three nights. “Three nights, double irons,” his records say. “For continued shirking.”

Later, he was held for five nights in double irons. In 1903 he went to sleep while he was supposed to be on watch, and he did 10 nights in chains. Jordan grew up hard and fast. By the time he was 20 he’d grown another six inches and put on 45 pounds of muscle, and he was feared and respected. The five years had done some things to him. Physical things.

He got a burn scar on his buttocks, though the records don’t say how. A three-inch scar on his abdomen. And scars on his knuckles, the type of scars one gets throwing a punch into another man’s teeth. His left ear was bent, the kind of thing that comes from getting hit hard, or wrapped in a headlock.

Jordan had learned one thing: to fight. The Navy decks and mess halls were the best school in the world.

Jordan had learned one thing: to fight. The Navy decks and mess halls were the best school in the world. He would have learned everything they could teach: to pace himself, to breathe right while he fought, to feint, to sidestep, to keep a sparring rhythm, and to break it. To take a punch. He made good money fighting in “smokers,” because the officers had begun to offer prizes to the winners.

And he earned himself a reputation, so somehow, as he got good at fighting, the brutal Navy discipline abated. He was winning boxing contests: $50 here, $100 there. Big purses that dwarfed his $9 a month salary. And since the records show he was no longer being put in chains, it is worth asking why. Did the fighting make him more disciplined? A better sailor perhaps? Was that why the punishment stopped? Or was it the reverse? Did the crew chiefs begin to cut him slack when he proved himself in the ring?

And it is fair to ask, of course, whether the crews really let him keep his winnings. A black boxer in the Navy, whose bouts were organized by his teammates: The idea that he could have really kept it all himself — the prizes were massive sums in those days — is not realistic.

The bell for round two rang, and the two men clashed again. Cohen, a bit more worn-down now, a joke of a boxer, against the more skilled Johnson, implacable and professional. But they moved with the speed of catchweight fighters.

The men clinched, and before the referee could push them apart, Cohen slipped a solid elbow to Johnson’s face. A sturkh, they would have called it in Yiddish on Suffolk Street. But the referee didn’t call anything, and Johnson kept fighting. At 20, Johnson was outwardly immune to racial taunts already. Hisses from the crowd, curses. It didn’t matter. He kept his eyes dead.

And then he landed an uppercut to Cohen’s gut, a good body shot, but it looked low. Suddenly the ring exploded.

“Foul,” yelled some sailors to the side of the ring. “Foul.” Cohen’s cornermen charged into the ring, and one grabbed Johnson by the neck and held him against the ropes. Johnson didn’t resist. He relaxed, dead eyes.

The referee, from the USS Detroit, muscled the two sailors away. He shoved one through the ring, despite the man’s bravado, and then freed Johnson and pushed the other one out of the ring, while the wild cheers from the sailors crescendoed.

And then the referee told Cohen and Johnson to fight on.

The money. Well, the prize money was at least $50. That’s about $1,400 adjusted for inflation. For Cohen, whose earnings were going to his wife in New York, it was a fortune. He had literally no money, and he’d been on board the USS Yankee for 614 days and counting.

And for young, battle-hardened Johnson, who was officially making $9 a month, it was half a year’s pay.

What wouldn’t an impoverished sailor do for that kind of money?

Watching from the bridge, Captain Qualtrough had enough. He headed back to his cabin with the visiting captain of the USS Detroit to leave the brawling behind and entertain his guest.

After Cohen fled his wife and his failed life in New York and signed up for a four-year enlistment, the Navy first sent him to an old tub called the USS Puritan. It was a receiving hulk, a legacy of the old press-gang days, functioning as a short-term floating prison where the Navy could stash its new recruits after signing their papers and they could learn their new trade. Salutes, uniforms, ranks. It was shock treatment for sailors.

And then he was briefly assigned to the USS Prairie for more training. Instead of adapting to the new discipline aboard ship as an apprentice, as young Johnson had, Cohen went through a rudimentary, structured system, a school that would transform him from a landsman to a seaman.

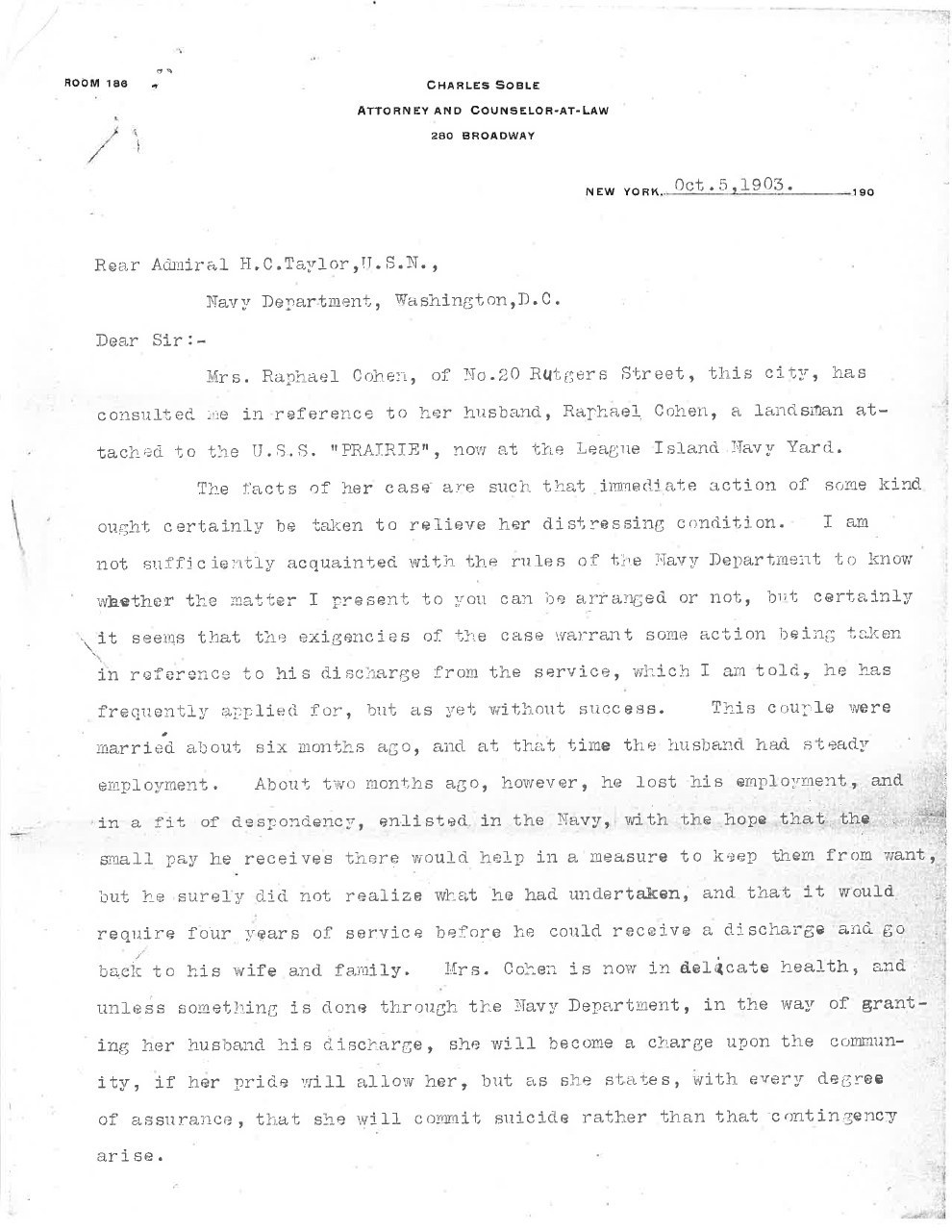

Here, it seems, Cohen’s abandoned wife, Sadie, found him. Perhaps he wanted to be found. Perhaps he wanted to be rescued. Perhaps he smuggled a letter to her because he wanted her help in getting out of the Navy. Whatever it was, Cohen had lied about her, ignored her, and denied her very existence, but Sadie wanted him back.

And Sadie did something very American: She hired a lawyer, Charles Soble, on Broadway. Soble did the best he could, pleading in a letter to the Navy bureau that Cohen be cut loose from his enlistment. “He surely did not realize what he had undertaken,” the lawyer wrote. It was a matter of life and death, the lawyer argued in a letter to the Navy Department. If Cohen wasn’t released, he warned, Sadie Cohen would “commit suicide.”

The letter underscores the extraordinary gap between the efficient bureaucracy of the Navy and the mystified citizens of the Lower East Side who had honed a completely unrelated set of survival skills. Admiral Henry Clay Taylor, chief of the Navy bureau, a well-respected hero from his service during the Philippines campaign, looked over Soble’s letter, and passed it on down through the chain of command. Was it because it was unusual and he got a laugh out of it? Or was he just part of a system that kept itself by the book? It’s unclear. But the captain of the USS Prairie talked to Cohen, who after all had denied being married when he first signed up.

Sadie’s efforts failed, of course. “The Bureau regrets,” the Navy wrote to the New York lawyer, “that his discharge cannot be authorized.” But Sadie did at least get some justice: Raphael now signed a document allowing his wife to get the bulk of his salary, which was $16 a month. It was good for her. Better than nothing, at least. She didn’t kill herself, after all.

And Cohen, he settled into his routine, and tried to prove he was a tough guy, as he worked shoveling coal in the boiler room of a ship and got paid little for it.

While black men like Johnson were being culled from the Navy, shifted away from roles of responsibility, Jews like Raphael Cohen were still slipping through. Their situation back then, at the turn of the century, was complicated. They were often despised by the other men. One Jewish Navy veteran wrote about the hard days before WWI: “The Jew was usually singled out in the service and woe to him unless he was more then able to take care of himself. He was the target for all sorts of jibes and insults.”

One novel captured some of this: Delilah, by Marcus Goodrich. The Jewish seaman aboard has to pull himself to the side on the deck when he passes another sailor, to avoid random punches to the gut. “A Jew had no business being a naval officer,” one lieutenant rambles in the book, “their blood and their guts were sour.” So some Jews kept to themselves to avoid confrontation. Cohen, it seems, handled it the other way, making brash claims. He boasted that he’d take on anyone in the whole fleet who was his size.

But on the other hand, Jews did have one staggering advantage over black sailors. No matter what anyone else thought of them aboard ships, they were classified as “white.” The views of the most powerful men, like Teddy Roosevelt, were certainly softer toward Jews than African-Americans. But even Roosevelt had his doubts. The famous Jewish boxer Abe Hollandersky said Roosevelt told him of his surprise at his skills, because people believed “a Jew won’t fight.”

Doherty, the timekeeper, hit the gong for the fifth round. Johnson danced from his corner, barely showing any fatigue 18 minutes into the fight. He moved crisply, his face still expressionless.

Cohen came out of his corner sluggishly. His cornermen, Benny and Jimmy, must have yelled what cornermen always yell in a fight like that: "Keep your hands up! Hands up! Keep your hands up, man!" His lack of skill was showing. There was blood from Cohen's nose and mouth.

A jellied froth of blood and sweat on his matted chest hair.

The crowd must have been more subdued now, because it becomes monotonous and irritating to watch a mismatched fight drone on. There’s a transitional point, when pity for a losing fighter becomes resentment and confusion. The beaten should stay beaten.

But Raphael Cohen refused to stay down. He’d been knocked down time and time again since the first round but he continued to stand. He was brawling, while Johnson was boxing. And sometimes, Cohen seemed to fall to his knees for a moment out of sheer fatigue, as if he were taking a rest. Before the count could start, he’d stand up again.

Johnson wasn’t aggressive in the round. He tagged him, biding his time. Then finally, more than two minutes into the round, Johnson let loose a punch to the body. Cohen stumbled.

Then as Johnson came in for the knockout to end the thing, Cohen tread backward and tripped. His head smacked the post and he collapsed to the ring.

Once again, the referee, Pettingill, stood over and began the dramatic countdown.

The onlookers would have chanted the numbers in unison. The fight was finally over, it seemed. Cohen lay there, dazed and staring again up at the now familiar sight of the bright lights overhead, against the Caribbean night sky.

Roosevelt was famous for his love of boxing, and he’d made it plain he wanted more sports in general, suitable for the “rough life,” in the military services. In fact Qualtrough would later say that the bout between Cohen and Johnson was in accordance with Roosevelt’s “desires.” On June 15, 1905, just a month before the fight, Admiral Robley Evans, “Fighting Bob,” passed some new regulations down to the fleet. Evans, a favorite of Roosevelt, and a hero of both the Civil War and the Spanish-American War, ordered that “Captains shall encourage athletics including boxing.”

Back in 1905, in the military and in civilian life, too, both African-Americans and Jews were just then emerging as some of the primary fighters in what was then a controversial sport in America. By the 1920s, about a third of all professional fighters were Jews. And as Jews climbed into the ring, black fighters increasingly did, too. In 1908, the legendary Jack Johnson, bald, brash, and big, became the first African-American heavyweight champion. He’s the subject of the 2004 documentary Unforgivable Blackness.

The truth was that even before Teddy Roosevelt’s orders carried on down through the ranks in 1905, some of the best American prize fighters learned their trade in the Navy, as boxing historian Mike Silver said in an interview with BuzzFeed News. Navy veterans who boxed boldly advertised that in their “noms de Swat,” as the Baltimore Sun once quipped. There was the great Sailor Burke, born in Brooklyn as Charles Presser, who would reach the pinnacle of fame in 1906 when he knocked out the iron-skulled Joe Grim. Or "Sailor" Tom Sharkey, who had a battleship tattooed on his chest.

And just as the Navy was churning out fighting professionals, so were the rough and crammed neighborhoods in civilian life. Jews and African-Americans were both getting into the fight game to earn their way toward money and respect. Leach Cross, born Louis Wallach, “the Fighting Dentist,” earned a name for himself. So did Abe Attell, “the Little Hebrew.” Raphael Cohen likely knew these names and followed the careers of the Jewish fighters, who were earning respect as tough and hardened men.

One of the best known Jewish fighters was the legendary “Chrysanthamum Joe” Choynksi, “the California Terror,” who was tough and calculating. Back in 1901, Choynski headed to Galveston, Texas, for an unsanctioned bout with the man who would change the role of African-Americans in boxing forever, Jack Johnson. Choynksi knocked him out in the third round. But the Texas authorities, after the fight, threw the black boxer and the Jewish boxer in prison together for three weeks, and Choynski became a mentor. Johnson would later say Choynski had the hardest punch of any man he’d fought.

The fleet was in the doldrums out at Monte Christi. The ships of the Caribbean squadron were seven months into a bizarre venture into gunboat diplomacy that would change the nature of U.S. intervention in the Western Hemisphere. A politically connected New York firm, the “Santa Domingo Improvement Company,” owned much of the Dominican debt and was trying to wring the small country dry with unforgiving tenacity, and the Dominican government didn’t want to pay.

In 1905, after repeated pressure from the Improvement Company, Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Caribbean fleet into Dominican harbors. Under the president’s orders, the American Navy took over all the country’s customs houses to launch a receivership. Functionally, the U.S. took over the finances of the Dominican government on behalf of the American company.

It was an unprecedented example of Roosevelt’s “Big Stick” strategy. But it wasn’t challenging for the crews of the ships, which steamed offshore to support the mission, and they all needed entertainment.

This time, Cohen didn’t get up, as he had in the first round. But the bell rang. His cornermen towed him to his corner stool.

And in an unusual move, the referee, Pettingill, would later claim he warned the battered man to give up. “You’ve lost the fight. Give it up, man.”

Cohen muttered back at him that he wouldn’t give up. “I’ll win yet,” Cohen — beaten, bloody, dying by now — supposedly muttered to the referee.

And then he recovered for the sixth round, on the corner stool, as his cornermen frantically splashed him with fresh water.

By the eighth round, Cohen was just a puppet of a man, shuffling though he was still on his feet. Blood was all over him, and on Johnson’s gloves, too. Every time Johnson punched Cohen, he was getting painted again with his own blood. In his brain, his hemorrhage had begun to block his ability to function. He was dying as he fought.

And then, finally, he fell for good. One spectator said it was a body blow that did it, though a news account claimed it was a blow to the temple. He tried to rise and then collapsed.

His cornermen dragged him from the canvas and propped him on a stool in the corner of the makeshift ring. Cohen sat, unable to talk. Did he want water? they asked. He could not answer. They rubbed him down, and then they hoisted up the man, and they levered him over the ropes, his body sloppily swinging as they hurried to the warship’s sick bay.

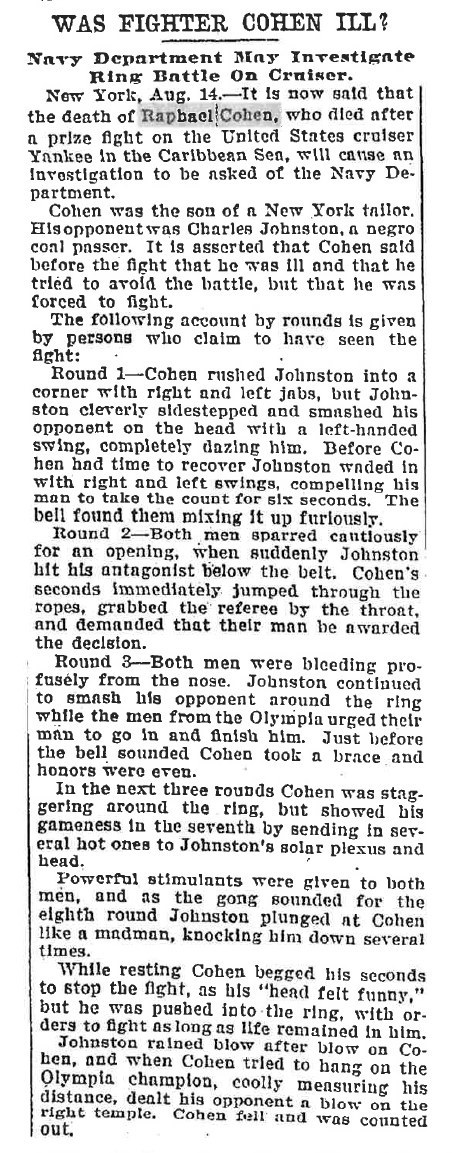

There are a few slightly distinct versions of how the final knockdown came. According to some newspaper accounts, Cohen and Johnson were both given “powerful stimulants” in the last round so they could keep fighting. “While resting,” the Baltimore Sun would later report, “Cohen begged his seconds to stop the fight, as his ‘head felt funny.’ But he was pushed into the ring, with orders to fight as long as life remained in him.” And then, the newspaper said, Johnson let loose a powerful left hook to Cohen’s temple.

But there is no mention in the official Navy records of “powerful stimulants,” and it’s tough to see what they might have been. If indeed they were used, could it have been something as simple as smelling salts? On the other hand, cocaine was then perfectly legal and readily available. Indeed, cocaine had been part of the Coca-Cola recipe till the previous year. The panic about the drug had not yet reached its crescendo, and the newspapers were yet to start a panic over what they would call the “Negro Cocaine Fiend.”

With $50 at stake, and no real rules, could the two sailors have been given cocaine to keep on fighting? Or, on the other hand, was it yellow journalism at its worst?

In the accounts of the official Navy inquest, Cohen took punch after punch to the head, and then finally took a body blow from Jordan, to the liver, perhaps, and he crumpled and fell to his knees. He tried one final time to pry himself from the ground, and then he collapsed. The fight was finally over. His cornerman threw in the towel.

And there’s one final version too by yet another man who claimed to witness the whole thing and described it to his mother: “Johnson the negro gave him a left-swing and sent him to the mat and just about the finishing of the count Cohen got on his feet and Johnson caught him another with his right and knocked him to the mat never to rise any more.”

There, it took a full two hours for Cohen to die. The fight in the ring, by comparison, had taken a half hour. For a short time, he briefly recovered, moaning, moving his eyes and even smiling. But at about 11 p.m. Assistant Surgeon William Levesky noticed that Cohen’s left eye no longer processed light. And his left arm seemed to be paralyzed. With his right eye, Cohen stared unmoving at a bare electric lightbulb hanging above the cot.

The Navy doctors were about to trepan his skull, to cut a hole in it to relieve the pressure, but he died before the operation got started. It was 11:30, and they did an autopsy just 40 minutes later, before his body was even cold. The doctor found what he suspected: a blood clot in Cohen's brain. It was a massive dull red slug of blood about three inches wide, caused by the beating.

Qualtrough issued orders the very next day, and a crew rowed the body to the dock in the morning in a whaleboat and buried Cohen in a plain wooden coffin in the Dominican port town, Monti Christi.

The captain quickly swore off any responsibility for the death. Cohen’s death, he ruled, in a final insult, was not in the line of duty. Qualtrough’s direct commander, Admiral Bradford, overruled Qualtrough. Cohen, the admiral decided, died while fighting aboard ship in a fight approved by the captain. He had clearly died in the line of duty, because he’d been on active duty at the time, and he hadn’t been engaged in any misconduct.

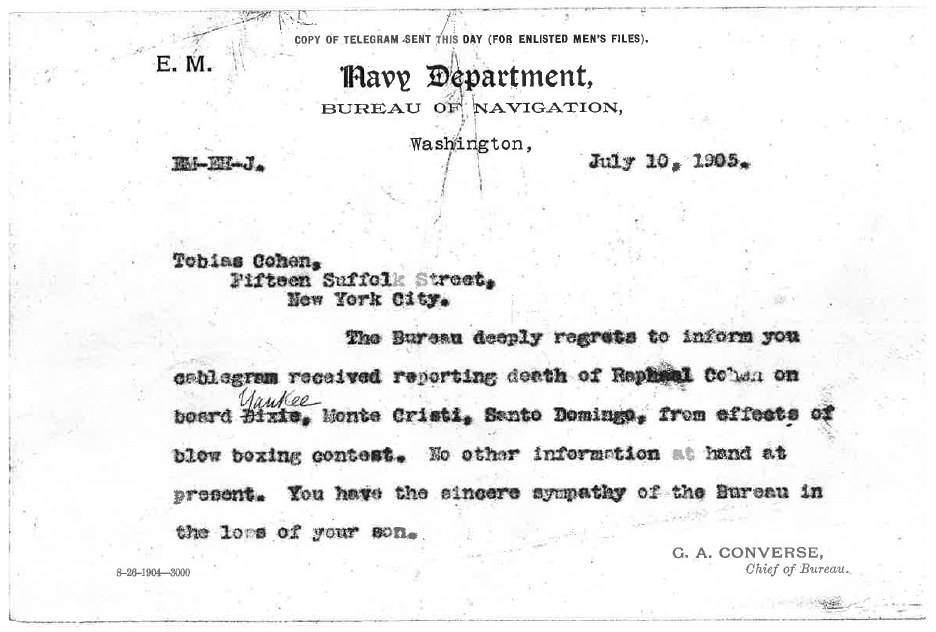

Back in New York, on Monday, July 10, 1905, a Western Union boy made his way through the thick crowds on Suffolk Street on foot. It was faster, in those cluttered streets, than by bicycle. At 15 Suffolk St., he stopped. There, he handed over his message, a telegram from the Navy bureau.

“The Bureau deeply regrets to inform you cablegram received reporting death of Raphael Cohen ... from effects of blow boxing contest. No further information at hand as present. You have the sincere sympathy of the bureau in the loss of your son.”

The captain quickly swore off any responsibility for the death. Cohen’s death, he ruled, in a final insult, was not in the line of duty.

The Cohens were confused. A klap from boksing fayt had killed their son? The first message from the Navy had even gotten the ship wrong, and accidentally said he died aboard the USS Dixie, not the Yankee. The Cohen family sent a telegram back to the Navy bureau the same day, asking for the body. Then they tried a letter, and long-distance phone calls to Washington, D.C. They wanted the body returned to them so they could have a Jewish funeral.

Soon they got the next telegram from the Navy: “Remains Cohen not embalmed and buried Money Christi [sic].” At first, the Cohen family thought they could have the body disinterred and shipped to New York. The Cohen family wanted to sit shiva — to grieve. “Brengen tsu keyver yisroel” was the way a Yiddish newspaper described it at the time. They got the final telegraph from the Navy later the next week. There would be no funeral in New York soon. “Local laws,” wrote the Navy officials, “forbid disinterment under five years.”

One can only guess why. Perhaps Hispaniola, half Haitian and half Dominican, had old fears of grave robbers stemming from the practice of voodoo, and Monti Cristi was right on the border, so the laws made a certain sense.

The next month, the newspapers across the country got hold of the story. The New York World, had it first, though it mistakenly called Cohen a Marine. But soon, the story became something of fervor. The headline in the Baltimore Sun was “Was Fighter Cohen Ill?” The Washington Post wrote “Sailor Killed in a Fight: Felled By Terrible Blow.”

But it quickly settled down. The Navy said no one was to blame, and the papers didn’t push any further.

Sadie, Cohen’s wife, had sent a letter to the Navy bureau to see whether she’d get any backpay, and to learn more. In 1907, the Navy sent her $12.45: the result of auctioning off things like Cohen’s clothes, blankets, and machete.

In 1911, the Navy dug up Raphael Cohen’s remains. They were sealed and shipped to New York, where his family buried him at Maimonides Cemetery in Brooklyn.

As for Jordan Johnson, he had done nothing but fight the opponent he was given. The admiral ordered a court of inquest, and Johnson was cleared of any wrongdoing. One spectator testified that Johnson had been repeatedly “hissed” at during the fight, though the referee insisted he heard none.

But Johnson left the Navy a year later, a scarred and hardened man and an expert fighter at the age of only 21. There was, of course, nothing left for him in the Navy after the scandal. He would have been too rough around the edges to make it as a white officer’s butler. He would have been shuttled down to the mess hall.

Johnson died penniless in Chicago in 1929, only 46 years old, his family lacking the money to afford a tombstone. His sister sent a note to the Navy asking for help to bury him.