Medical science is being undermined because researchers are changing the things they're measuring after looking at the data, a campaign group has warned.

The CEBM Outcome Monitoring Project, COMPARE, part of Oxford University's Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, says that the top five medical journals all regularly publish articles with switched outcomes, and that it is a huge problem for science.

When a research project begins, its authors record the things that they're going to measure at the end. "Outcome switching" is when they measure different things instead, without telling anyone.

So, for instance, if you propose a study into the effects of alcohol on health, you could say that you were going to look at 10,000 people who drink and 10,000 people who don't and look at how many in each group die within five years.

It would be "outcome switching" if, at the end of the trial, you count how many heart attacks there were, instead, without admitting in the article that you originally planned to count the number of deaths.

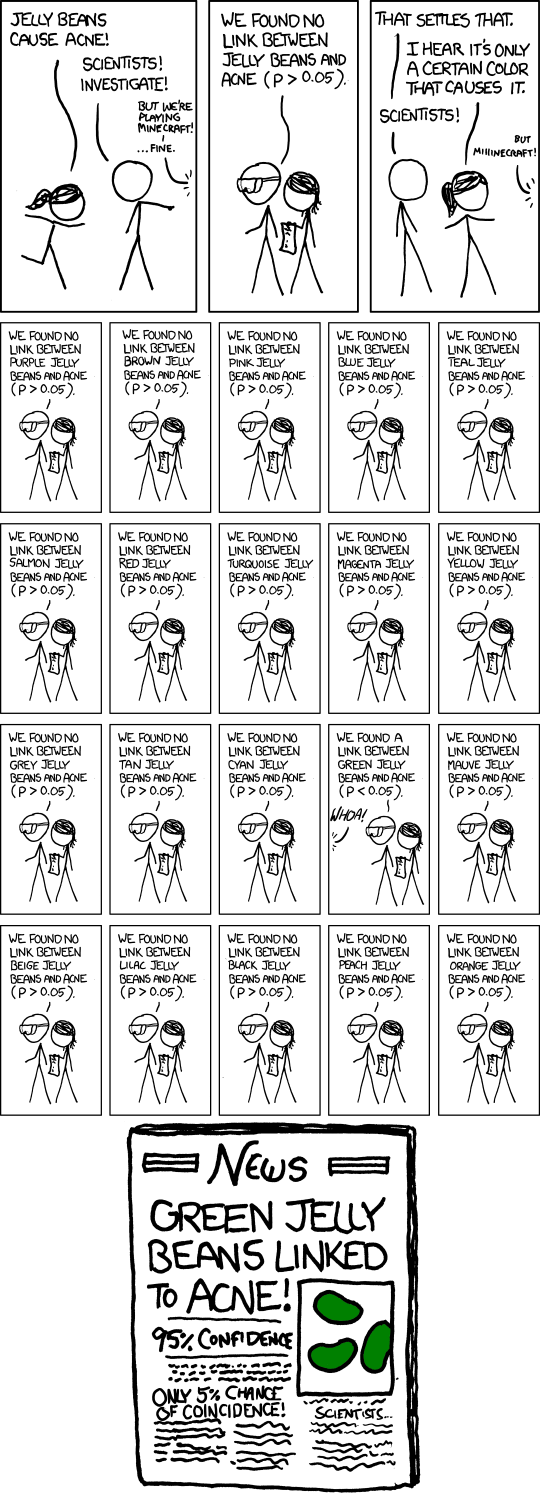

This matters, because sometimes, you'll get good results just by chance. The more things you measure, the more likely you are to get a fluky good result.

A professor of cognitive neuroscience told BuzzFeed Science: "Hidden outcome switching is like choosing lottery numbers after watching the draw."

Chris Chambers of Cardiff University said: "Who would be surprised if you picked the winning numbers? In medical science the problem we face is much the same.

"To be as sure as possible that a discovery is real, we pre-specify outcome measures, run the study, and then rely on statistical tests to tell us how likely a particular outcome was compared to chance."

Not doing so, he said, "can have devastating downstream consequences for medical treatments", because the science that doctors are basing their treatments on becomes unreliable. "The issue boils down to transparency," he said.

COMPARE looked at 67 articles published in the top five medical journals since October 2015, to see how many had changed outcomes without saying so. All but nine of them had.

This goes against guidelines for transparency in research. The CONSORT guidelines, which all five of the journals have signed up to, state that any changes to outcomes should be publicly declared, and reasons given. "If you switch them, that's fine, but you've got to say that you switched them and why," said Goldacre.

The group then sent letters to each of the journals, pointing out that the outcomes have been switched and asking them to publish clarifications.

For instance, one trial in the Lancet said it would measure 22 outcomes; COMPARE wrote to them pointing out that it had only published results on 14 of them, and had added an extra one which wasn't mentioned. Another, in the Annals of Internal Medicine, had two prespecified outcomes; it published results for neither of them, and added a further 14 outcomes in its published study.

The journals have responded very differently, Goldacre said. At one end of the spectrum, the BMJ has "set the standard".

He told BuzzFeed Science that the BMJ had "published all our letters, accepted it had misreported outcomes, and issued corrections. That's what you'd expect a good journal to do."

By contrast, the Annals of Internal Medicine's response was "extraordinary and confused", he said.

They issued a letter signed by the editors, saying that "On the basis of our long experience reviewing research articles, we have learned that prespecified outcomes or analytic methods can be suboptimal or wrong."

However, they did not explain why declaring when outcomes have been changed would be a bad idea. Goldacre said that "They essentially argue that outcome switching is fine and that they have the skill to allow people to do it, which breaks the promises they've made [to CONSORT] and the expectations their readers have that they are properly managing the problem."

Chambers agreed, and called Annals' failure to respond "nothing short of astounding". "Quite frankly, the response of Annals to this basic scientific issue betrays a disappointing ignorance among the journal's editors about the purpose of trial registration," he said.

Goldacre said: "We are confident that [Annals] are committed to addressing this problem, but there is a deep-rooted cultural problem in science and medicine about accepting these bad practices." COMPARE responded to the Annals editorial in a blog post.

A spokesperson for Annals of Internal Medicine told BuzzFeed Science that they had addressed the issues in their letter.

A spokesperson for the BMJ, meanwhile, told BuzzFeed Science: "The BMJ supports the aims of the COMPARE project. We are committed to publishing research papers in which the pre-specified outcomes listed in the trial registration are faithfully reported or the authors declare their intention to publish the outcomes elsewhere."

CORRECTION

The Annals of Internal Medicine published a letter signed by its editors in response to COMPARE's comments. An earlier version of this piece described this as an "anonymous editorial".