I met director Roland Emmerich at the historic Stonewall Inn where, in 1969, a band of queer and trans street hustlers once rioted for justice. More than 40 years later, Emmerich has attempted to immortalize those riots, which are widely considered a watershed moment for the queer liberation movement, in his new film Stonewall – an endeavor that has landed him at the heart of a great big gay controversy.

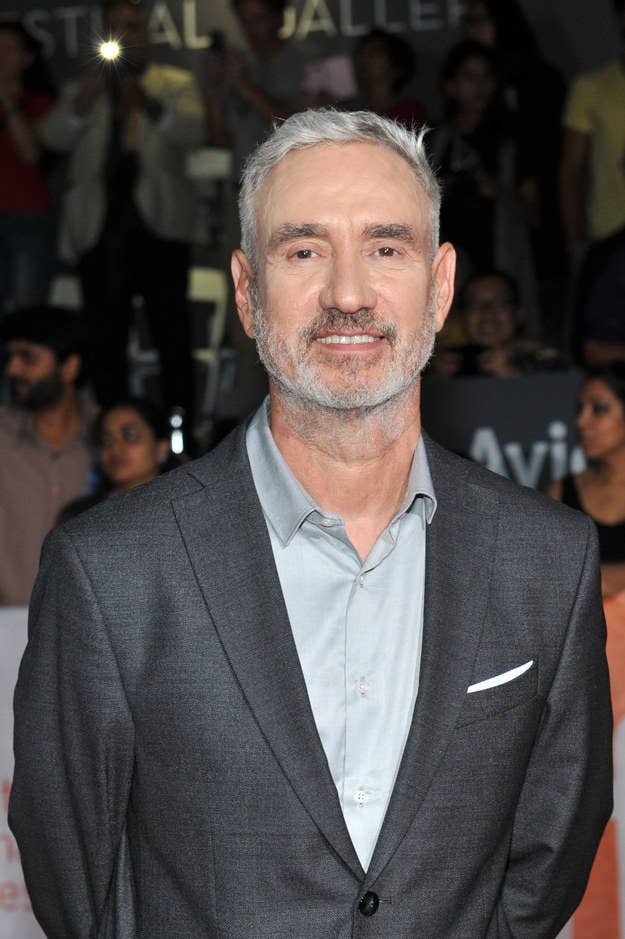

We sat upstairs in a quiet corner of the bar, midday September sun streaming through the windows behind us. Emmerich wore a blue velvet jacket over a white tee. He looked casually dapper, if slightly tired. He’s been surprised to see the Stonewall backlash, which began long before the film’s release this upcoming Friday. “When [the criticism first] happened it wasn’t about the film, it was about the trailer,” he said. “And I thought, That’s not right.”

The trailer depicts the film’s handsome white protagonist, Danny Winters (Jeremy Irvine), arriving in the West Village on a bus from his Indiana hometown, meeting a colorful gang of queer street femmes and tossing the first brick to incite the Stonewall riots, which would inspire the first Gay Liberation March a year later in New York City. Critics online quickly took issue. From the looks of things, said naysayers, Danny — a fictional character inserted into a historical event of monumental significance to the LGBT community — was being painted as Stonewall’s hero, rather than the real-life trans women, butch dykes, and drag queens of color many argue were at the forefront of the turmoil that hot summer night.

But Emmerich wasn’t caught completely off guard by the negative reactions. “Some people warned me,” he said, referring to the waves of angry takes under which he’s since found himself. “But I said, ‘Well, you know, so be it.’”

The trailer doesn’t mischaracterize Emmerich’s film: Danny is the centerpiece of Stonewall, a decision Emmerich made, in part, in an effort to attract a wider audience who could connect with him. “You have to understand one thing: I didn’t make this movie only for gay people, I made it also for straight people,” he said. “I kind of found out, in the testing process, that actually, for straight people, [Danny] is a very easy in. Danny’s very straight-acting. He gets mistreated because of that. [Straight audiences] can feel for him.”

Emmerich, who has previously directed blockbuster features like Independence Day, Godzilla, and The Day After Tomorrow, said he wanted to educate young people about the riots. He felt the best approach would be a personal one. “When do we see a personal film from you?” Emmerich said his friends kept asking him before he took on the Stonewall project. It’s partly because of the personal element imbued in the film, Emmerich said, that has led to some of the protests surrounding his approach. “As a director you have to put yourself in your movies, and I’m white and gay,” he said.

He added that he was inspired to tell this story when he met a young man at the Los Angeles LGBT Center who told him about growing up in the rural heartland of the United States. Emmerich himself grew up in the German countryside, and he felt compelled to shed light on the harrowing statistic that 40% of homeless youths in the U.S. identify as LGBT by focusing on small-town familial rejection. Danny, whose father is also his football coach, gets kicked out of his home when he’s caught fooling around with the quarterback, forcing him to flee to New York. (Since homelessness and harassment disproportionately impact LGBT youths of color, some of Emmerich’s critics have accused him of whitewashing the social and political climate of Christopher Street in 1969.)

Emmerich sees Stonewall both as a coming-of-age tale and as a story of unrequited love. The film intercuts scenes of present-day Danny in the streets of New York with numerous flashbacks to his recent past. Near the film’s end, Danny returns to Indiana, where he again professes his love to the quarterback who rejected him after claiming he had been unknowingly seduced by Danny while drunk.

With this storyline, Emmerich wanted to impart the truism that some queer people aren’t capable of acting on their queerness. “When a gay person is attracted to somebody, that doesn’t mean that they love somebody,” Emmerich said. “That doesn’t mean that he gets loved back. Even me, all my life, I would love somebody, and that person would be ... straight, and he couldn’t love me back. Or he was not as courageous, maybe, as I was, in fulfilling sexual needs. There’s a lot of people who are just afraid of society and how they get ostracized.”

Emmerich sees Danny’s story of struggling with rejection as a gateway to the story of Stonewall. “Danny is like the catalyst,” he said. “[The street hustlers] teach him about survival. Through him, we experience them.”

This lens — experiencing the riots through Danny’s eyes and actions — is one of the primary reasons over 24,000 people have signed a petition, started by trans woman Pat Cordova-Goff, to boycott the film. The petition claims that Stonewall fails to “recognize true s/heroes.” Of the street hustlers populating the film, some are based on historical figures who were present at the time of the riots: Otoja Abit plays Marsha P. Johnson, the black trans leader who later co-founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), and Ray, Jonny Beauchamp’s character, is a composite of multiple people, including Latina trans rights activist and Johnson’s fellow STAR co-founder Sylvia Rivera.

Emmerich said that deciding which of the real-life heroes to include involved long, frequent discussions with the film’s screenwriter, Jon Robin Baitz. But Marsha P. Johnson is the only clearly discernible trans character in the film; Emmerich said that in consultation with historians and veterans, he concluded that “there were only a couple of transgender women in the Stonewall ever. They were like a minority.”

Not all Stonewall veterans agree with that assertion. In an interview with Autostraddle, Miss Major Griffin-Gracie, a black trans woman present at the time of the riots, remembers that it was actually cisgender people in the minority that night. “I’m sorry, but the last time I checked, the only gay people I saw hanging around [the Stonewall] were across the street cheering. They were not the ones getting slugged or having stones thrown at them,” she said. “It’s just aggravating. And hurtful! For all the girls who are no longer here who can’t say anything, this movie just acts like they didn’t exist.”

The petition to boycott Stonewall also takes issue with Ray, the most prominent character of color, falling in love with Danny — critics read that particular arc as a White Savior narrative. Emmerich, for his part, thinks that Ray and the other street hustlers benefit from Danny’s presence, even after Danny leaves the Village to begin his freshman year at Columbia.

“They learned something from Danny — that you can make it, that you can study, you can maybe have a more regular life,” Emmerich said. “I also don’t have the feeling at the end that they are so much on the streets anymore.”