At the peak of her powers — back in the mid-’70s, when she was essentially practicing therapy on stars while millions watched — Rona Barrett drove around Hollywood in a Rolls-Royce with a license plate that read MS RONA, the nickname she’d picked up when she first started delivering Hollywood tidbits at the end of the ABC evening news. She wore miniature heels for her size 5 feet and massive minks on her 5-foot frame, crowned with a layered bob (“like an artichoke”) dyed platinum silver.

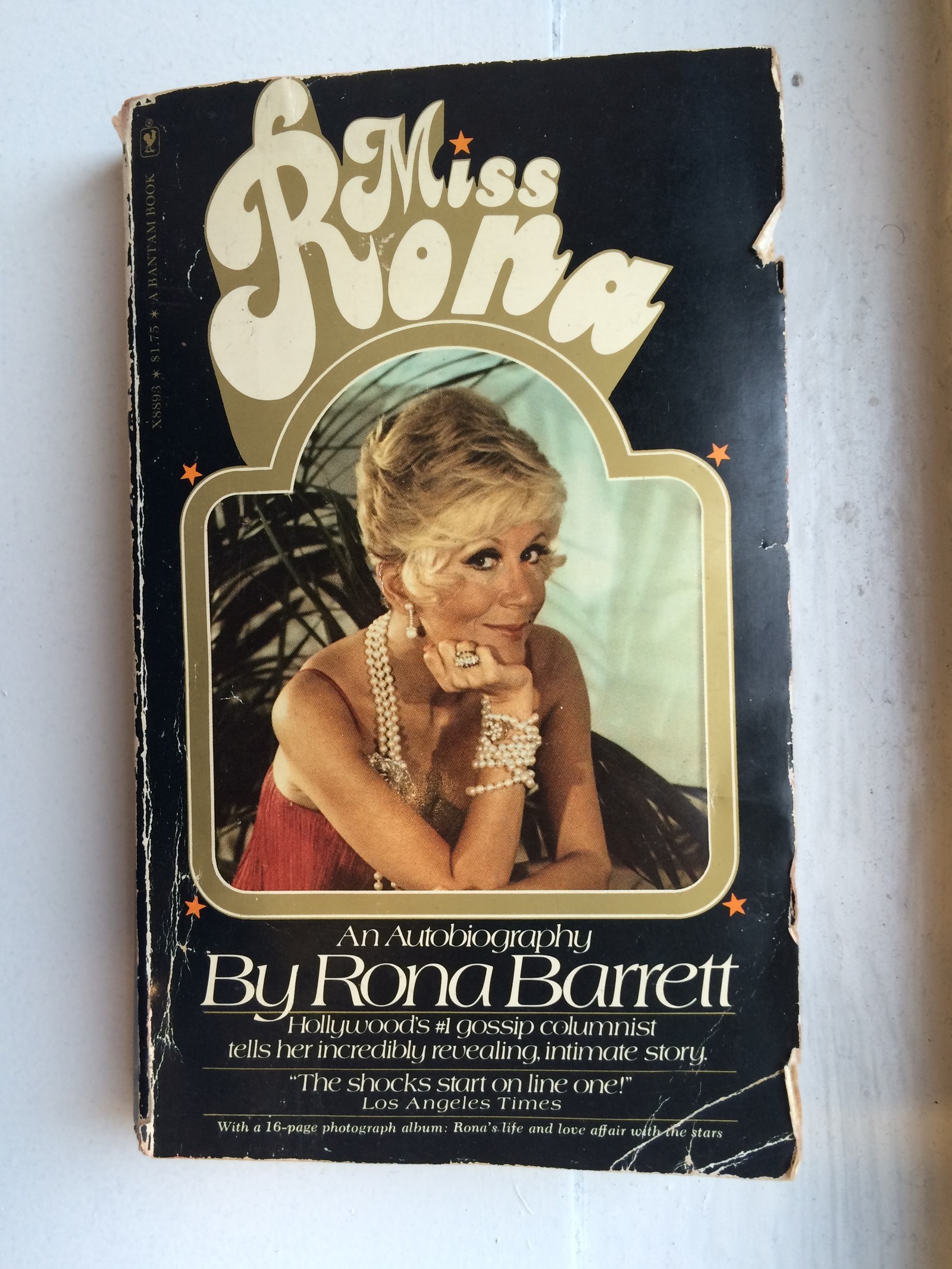

Her 1974 memoir, Miss Rona, had sold over half a million copies, in part due to its irresistible lede: “Just an inch, Miss Rona, just let me put it in an inch!” Barrett attributed the come-on to a “major masculine Hollywood star,” and rumors swirled as to his identity. It couldn’t be Frank Sinatra, who'd taken to calling Barrett horrible names at every concert — or Love Story star Ryan O’Neal, who’d sent Barrett a live tarantula. Some guessed it was her neighbor, Kirk Douglas, whose Hollywood estate backed up onto hers. But Barrett would never confirm. Sparking that sort of speculation was what Barrett did best: Every broadcast was an invitation to join her in the campiest, dirtiest game in town.

Over the course of her 40 years in the gossip industry, Barrett became known as a ball-buster, an indefatigable reporter, and a legitimate pioneer. Her name has faded from national consciousness, yet her innovations remain: She was Barbara Walters and Nikki Finke and TMZ all rolled into one, and she did it first. Reporting industry information — power shake-ups at the studios and box office figures — for a national audience? That was Miss Rona. Hosting hourlong interviews with Hollywood stars? Rona. Getting those stars to talk frankly about sex on national television? All Rona.

Barrett had three magazines emblazoned with her name. She was on Good Morning America every morning. Her voice could be heard on syndicated gossip segments on radio stations across the country. She had three books, a staff of dozens, 11 phones in her house, and a web of informants that spread down Sunset Boulevard and into Europe. “Of the thousands who had covered Hollywood over the decades,” industry observer David McClintick wrote, “none had garnered the fame that had come to Rona Barrett by the late ’70s.”

Not the old biddy gossip columnists like Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons who moralized over classic Hollywood, not the sharp-tongued Walter Winchell. Barrett wasn’t just a gossip. She was, as one columnist put it, “the Czarina of Hollywood.” But unlike Hopper, Parsons, and Winchell, all of whom have been memorialized in extensive biographies and onscreen, Barrett has faded from popular memory. “I know the name,” Elaine Lui, who’s established a mini gossip empire of her own, told me. “And what she did with TV gossip. But that’s about it — that she was my trailblazer.”

These days, Barrett doesn’t talk about celebrities unless you get her talking about the past, where they pop up in the most unexpected places: young Warren Beatty, in the middle of the night, at the tiny New York apartment Barrett shared with four girls; Elizabeth Taylor, at the vanity in the ladies' room of a Hollywood nightclub, bemoaning the size of her breasts, the width of her shoulders. Get her going, and Barrett will offer quick takes on every celebrity from her heyday. Trump: “He didn’t know how to smile, and kept Ivana in the doorway.” Cosby: “We all knew; he was always on the make.” Travolta: “That one’s an odd duck.” Natalie Wood: “I think everyone instinctively feels that something more happened than her just slipping off the deck of the boat and drowning. It's hard for me to say the story that I was told [about her death] — by someone who was around every single day during that time. But I believe that person knows what happened.”

Who was your favorite interview, who was the most handsome, who was gay — Barrett gets those sorts of questions all the time, but they bore her, or at least betray the thoughts of someone who hasn’t really thought about Hollywood. What interests Barrett — what gets her pounding the table — is what a self-described “crippled, plain, fat kid” had to go through to legitimize herself and the subjects she covered. Today, that struggle feels especially poignant, in part because Barrett’s significant contributions, like her name, have been almost entirely elided, but also because female journalists still fight to be taken seriously, or treated with the same esteem — and pay — as their male counterparts.

But it was Barrett who took herself out of the game. Liz Smith is still writing gossip at 93, and Barbara Walters only recently retired from The View. Barrett — who doesn’t believe in aging, just “phasing” — essentially disappeared. She moved to the Santa Ynez Valley, 30 minutes outside of Santa Barbara, and phased forward: running a lavender farm, building a retirement community for low-income seniors, and looking, at age 79, fucking fabulous.

Barrett’s memory is precise; her corrections to the historical gossip record, including her own achievements and innovations, are exacting. But she has neither a score to settle nor an ax to grind: She agreed to talk only because she knew it would publicize her quest to provide housing for low-income seniors. She’s deeply amused at the idea of people under 40 knowing her name. She told me, without hesitation, "This is the best phase I’ve ever been in.”

When I first meet her on a foggy spring morning, she’s in a two-piece getup that looks like a cross between silk Chinese pajamas and a pantsuit. A heaped coil of a ring sits on her right hand; a massive opal on the left. She’s wearing reading glasses — bright pink frames, huge in the manner of the 1970s and the Olsen twins in the 2000s — to look at the computer, affixed with a Post-it with her Skype name and password. Her jet-black eyeliner is perfect; her hair — thick, white, still lustrous — is set in an immaculate chin-length bob.

Barrett’s handshake feels like a welcome and a warning, which must have been what it was like to be around her at the height of her powers: Part of you wanted to tell her everything; the other part knew better. “So,” she said, staring me in the eye. “Let’s begin.”

“The main thing in my life is that I was born with a disability,” Barrett said in the metered, deliberate voice of someone who’s conceived of her life in memoir form. That disability, an undetermined form of muscular atrophy, put her in and out of hospitals for the bulk of her childhood as Rona Burstein, the oldest daughter of middle-class Jewish parents in Queens.

“That made me feel different,” she said. “And therefore, my curiosity factor was always up: 'Why did you say that?' I’d say. 'What did you mean by that?' And by high school, everyone came to me. They’d say things like, ‘Oh, I love this girl so much, Rona, she let me feel her titties!’ Then another guy would come by and say something similar. And afterwards, I realized: I never want my name to be in any man’s mouth like that.”

Barrett decided, then, to keep herself apart: “I became the confessor,” she explained. “I was the priest.” She was also fiercely ambitious. At 13, Barrett took the train to Manhattan and simply showed up in the office of the record company that represented Eddie Fisher — then just a young, handsome singer who Barrett had seen perform up in the Catskills — and offered to start a fan club.

At that time, fan clubs were loose, unorganized associations. Barrett wanted to turn them into something more like political organizations, with the attendant might, and lobbying potential, to actually get a singer’s records played. She saw, in a way not even Fisher’s managers could, the cultural and financial power of her generation — and how to wield it.

"I became the confessor — I was the priest."

Barrett also understood the power of a name. When she introduced herself at the agency, she switched her birth surname to the less Jewish-sounding Barrett. Any notion of fan worship was also quickly disabused: Even as Fisher’s stardom expanded, in many ways thanks to Barrett’s work with the fan club, he hated Jewish girls. “Jewish girls are nudges,” Barrett overheard him say. “I wouldn’t date a Jewish broad if my life depended on it.”

Through the years, Fisher’s internalized anti-Semitism stayed with her. She was reminded of it every time someone told her how “smart” she was to have changed her name, and in the overarching unease when she started pitching the television networks. “I couldn’t put my finger on it until one day, a second-in-command took me aside," she recalled. "‘You’ll never see yourself on national TV as long as there’s a single trace of Brooklyn in your voice.’ A trace of Jew, he meant.”

Barrett graduated from high school early and enrolled at NYU, but dropped out just a few credits shy of a degree. She was a fixture at Downey’s, a Midtown restaurant where all the up-and-coming talent hung out: Paul Newman, Sidney Poitier, Tennessee Williams, Joanne Woodward, Elia Kazan. She found work as a “girl Friday” at the largest pulp publishing houses, named for their cheaply produced magazines and genre novels. At the time, the majority of fan magazines were stuck in the past — classic Hollywood was dying; the types of stars, and mores that accompanied them, were slowly going out of fashion. Only the middle-aged ladies wanted to know what was going on with Clark Gable and Joan Crawford: The new audience wanted Dean and Brando and Natalie Wood and Elvis.

That was a swath of stardom Barrett, who’d positioned herself in the thick of the community, knew she could own. “You could see that there was going to be a sea change, and I wanted to be part of it,” Barrett told me. In late 1958, Evelyn Payne, the new, hip editor of Photoplay, bought Barrett’s idea for a column on “Young Hollywood” and sent her to Los Angeles, where she moved in with a then-unknown Michael Landon and his wife. New York friends introduced her to L.A. friends; press agent friends started spreading the rumor that she was the heir to Winchell and Parsons. The more people said it, the truer it became.

Barrett had her nose “fixed” without compunction, but still felt she needed to slim down to fit in with all the Mia Farrow types waifing around Hollywood. So she made an appointment with a woman named Louise Long. “She’d modeled Marlene Dietrich’s face from round to gaunt,” Barrett wrote in 1974. “She’d made Kim Novak from a Polish cow into an American princess.” And she did it, supposedly, through deep tissue massage — and the help of one of those old, vibrating bands of fabric you can still find in the corners of YMCAs.

After 10 appointments, Barrett says, her entire body was resculpted. She knew it was effective when, weeks later, a male star decided to casually take off his shorts during an interview — a come-on which Barrett gently rebuked, as she did with all advances from the stars. “Because they never got ‘into me,’” she explained, “I was able to get in them all the more.”

In this way, Barrett insinuated herself into the group of young, up-and-coming stars who were crossing over from movies to television to music and back again: Frankie Avalon, Nancy Sinatra, Fabian Forte, Tommy Sands, Jimmy Darren. Most of her information, Barrett recalled, came from things she overheard at parties. “I always weighed my words carefully,” she explained. “I never broke a confidence, never wrote to hurt anybody, believe it or not.”

But she had little tolerance for celebrity bullshit. At press junkets where every star was giving canned answers, Barrett says she’d walk up to people and say, “Do you make a hundred thousand dollars a year yet?” or “How good a fuck are you?” or “What did you really think of your half-assed co-star in your last picture?” The stars might not have answered those particular questions, but it veered them off the well-worn publicity track toward something like a real answer to the questions that followed.

In 1960, Photoplay rival Motion Picture offered Barrett more money for her column, but with one stipulation: that she “take out after someone” every month. After years of simpering, moralizing banality, the fan magazines were suffering a crisis of consciousness: In the mid-’50s, scandal magazines, Confidential foremost amongst them, had exploited the newfound freedom of the Hollywood stars who, released from the protection of their studio contracts, had no apparatus to protect them when they misbehaved. Once readers had tasted real dirt, the fan magazines were forced to pivot to meet their demands. Barrett didn’t want to dish scandal like Confidential — which, even today, Barrett describes as a “terrible magazine.” Instead, she would highlight some hypocrisy, some wrong.

And she knew exactly who her first target would be: Frankie Avalon. “There was something about Avalon I had always found disturbing,” Barrett later wrote of the teen idol, who was a sort of Zac Efron meets Justin Bieber for the late ’50s and ’60s. “I was never sure if he had a sincere bone in his body. He was like a prostitute at heart. His parents had grown up believing that Jews had purple horns.”

She’d walk up to people and say, “Do you make a hundred thousand dollars a year yet?” or, “How good a fuck are you?”

But Avalon had been part of the “group,” and the group helped each other out — which is what Barrett did when Avalon impregnated a groupie who’d camped outside of his house in her car. To protect Avalon, Barrett helped pay off the groupie and kept the rumors at bay, but when the groupie’s demands went public, Avalon turned his back on Barrett. When the time came, Barrett had no qualms about giving the dirt on Avalon — not in the pages of Motion Picture, nor in her own memoir.

That was the beginning of Barrett’s gradual distancing from her Hollywood friends. She still moved in the same circles and was invited to the same parties; stars still used her as their confessor. But the understanding that she could tell all hovered around every pseudo friendship. Especially when, in 1959, she traded her monthly magazine work for a daily newspaper column, soon available in 125 papers across the nation.

It was during this time that Barrett, who had never been a prude, found herself knocking up against the old-fashioned morals of the publishing industry. She wanted to write about the prevalence of marijuana at Hollywood parties, or the female stars who were telling her they were thinking of having babies out of wedlock, but her editors would always mark it out — “Really, Rona, is this necessary?”

So Barrett refined the high gossip art of encoding: who was gay, who was high, who was sleeping with whom. “You could write in a way that was clever and smart, and people knew what you were saying," she told me. "Especially the world of gay people, the LGBTs. I think they fell in love with me because I was so honest, in a way, about it, and not making fun of it, but being more like, ‘Come on, you guys, you’ve got to be kidding me.’”

Barrett was comfortable printing an innuendo about Cary Grant — that he was “really more of a mother than a father to his daughter Jennifer” — but drew the line at outing people. Like Rock Hudson. “I went to his house one night for a cocktail party. And he knew that I knew that he was gay,” Barrett told me. “But he was always so polite — that’s how they were brought up in the studio system: They had to go to etiquette school, and then the PR people made up all of that stuff,” she said, gesturing to an old fan magazine with Hudson and “ROCK, ARE YOU GOING TO MARRY DEBBIE?” on the cover. “But the point was, if he wanted to come out and say it, it was up to him to say.”

After half a decade in Hollywood, Barrett felt stagnant. Her column was available in 142 cities, but they were all midsize markets; she had been flying to New York every year to pitch a talk show, but the networks had remained resistant. She was about to quit everything when, as Barrett tells it, she got a call from KABC, the local ABC affiliate. They wanted to put her, dishing a quick minute of gossip, at the end of the evening news hour. If she could get rid of her "Jewish" accent, the slot was hers.

Once she was on TV, Barrett’s appeal — hammy, winking, confident — was immediate. “It’s inane. It’s trivial triumphant. It’s delicious,” the New York Times raved. “Throw away the pills and tune in Rona.” Her “minute” expanded from one to two and a half, and she was picked up not just on KABC, but on the ABC affiliates in the top five metropolitan areas. She established her credibility by breaking the news of Elvis’s forthcoming marriage to Priscilla; she told the world that Mae West’s secret to staying young was a daily colonic; she called Raquel Welch “the two and only.” By 1969, 40% of the country could see Barrett five days a week.

Barrett’s gossip was juicy, but her true power within the industry stemmed from her willingness to cover it. She reported that Darryl Zanuck, who had recently handed the reins of 20th Century Fox over to his son, was ready to show him the door. “I covered that saga with such accuracy,” Barrett said, that “Darryl threatened to get ABC to fire me” — allegedly because her reporting was affecting Fox’s stock. She made trade gossip — Hollywood lawsuits, shake-ups, and troubled productions — into national news.

Years later, when she was a regular fixture on Good Morning America, Barrett found herself in a fight with an executive. “He started yelling at me, ‘What the hell are you doing telling everyone how much money a film made over the weekend at the box office! Who in America wants to know that?’ So I looked him in the eye and said, ‘Lemme tell you something. There are only three things in life that people are interested in: money, sex, and power, and not necessarily in that order.’” Barrett was combining all three.

From the start, Barrett’s broadcast was a mix of high and low, camp and news, troubling the distinction between the “hard,” masculine news (delivered by serious white men) and the “soft,” feminine gossip (delivered by frivolous women). The resultant tension was exacerbated when ratings on the nightly newscasts began to climb — in Los Angeles, the station had more than doubled its ratings, lifting it from a lagging third to tied for first with CBS. “They don’t like the fact that I’m getting the ratings, the news guys,” Barrett told the Times. “Tough. Now they have to acknowledge me, reluctantly.”

On the New York broadcast, that “acknowledgment” manifested in a cloaked misogyny. Every night, news anchor Roger Grimsby crafted a newly insulting introduction: “Here’s Rona Barrett, Hollywood’s tripe caster”; “Here’s Rona Barrett, keyhole ferret”; “Now here’s the woman who made 'broad casting' two words.” Barrett keenly remembers when Grimsby reported a story of three children who locked themselves in an abandoned fridge, never escaped, and were discovered in a garbage heap — then segued into Barrett with “And now here’s some more garbage.”

“I was just trying to find my way,” she told me. “No one had been doing what I was doing on television. It’s funny, though — I think of the fact that back then, if you were a woman and wrote about politics and D.C., you were a Washington gossip. If you were a man, you were a columnist. Men got a different respect. We were always belittled.”

Which is part of why Barrett couldn’t get her broadcast picked up by ABC national. “I hear Elmer Lower, the head of ABC News, sends memos daily to get me fired,” she told Life magazine in 1969. The trouble was Lower himself, who had been striving to make ABC's news division competitive with CBS and NBC. And Lower’s vision did not include a Hollywood columnist.

So Barrett quit. She found a better deal, with a boss who didn’t resent her, at Metromedia — a chain of stations in major markets across the U.S. She forged a deal to produce magazines with her name and general ethos, and Metromedia’s syndication numbers climbed 56%. She was always at the end of the broadcast because, as one Metro exec put it, “you always put the bread at the back of the supermarket.”

And she published her memoir, a compulsively readable telling of her upbringing, her early days in the fan mags, the anti-Semitism and sexism she faced, her struggle to find love, and her marriage, at age 37, to producer Bill Trowbridge. It sold over half a million copies. By 1974, Barrett had established herself as a multimedia brand and a bona fide celebrity, pulling in $300,000 a year (more than $1.4 million in today’s dollars) through her various enterprises.

Miss Rona overflowed with blind items about what and who she’d seen and fucked — a word, and an attendant dedication to frankness, from which she did not shy. There was a gentleman in D.C., high-powered in the Johnson administration, and “Marc,” the quasi boyfriend who tortured her through his refusal to commit. There was the man who begged for “just an inch,” and the dozens of others who revealed themselves, in various ways, as scoundrels, assholes, and in the case of one “leading male idol,” a perpetrator of domestic abuse, beating his girlfriend in the early morning hours after he found her at Barrett’s Hollywood apartment.

“That was Troy Donahue,” Barrett told me, sighing deeply. “It was very hard to witness that. I told her she could not go back to that relationship. And shortly thereafter, Troy married Suzanne Pleshette, and then he started beating her up. That’s when I lost them both. Suzy, who’d been my roommate back in New York — she wouldn’t speak to me. Not for many, many years.”

“There were so many men who wanted to help you go from the gutter to the sidewalk. But once you hit the sidewalk, millions of them wanted to shove you back down.”

She burned other bridges. Frank Sinatra wouldn’t dare badmouth her to the press, but regularly called her an “ugly broad” and worse at concerts. Tony Curtis dubbed her a liar. Ryan O’Neal mailed her the tarantula. After she reported that “Mia Farrow spent New Year’s Eve roaming from party to party in terrible condition. She wore no shoes. However, we overheard one of her friends say she made a resolution to take more baths a year,” Farrow and a date dumped a bucket of champagne on her at a Hollywood party.

“There were so many men who had wanted to help you go from the gutter to the sidewalk,” Barrett said. “But once you hit the sidewalk, there were millions of them who wanted to shove you back down.” Yet the more animosity she attracted, the more powerful she became. She had unprecedented access. She was incredibly popular. Still, “if a man had my job,” she told the Chicago Tribune, “He’d be making the same money for television alone that I make from TV, the magazines, books and lectures.”

That sense of inequality led Barrett to leave Metromedia in 1974. By that time, Barrett had been hosting hourlong specials in which she interviewed celebrities at length — a practice she continued at NBC, honing an intimate style in which she often sat just beside the subject. Or, in the case of Cher, next to her on the bed: “That interview with Cher!” Barrett exclaimed, throwing up her hands. “That became such a famous one, and just because we sat on a bed!”

Barrett’s approach was a mix of authentic interest and sneak attack. “I could get them to open up because they always knew I cared,” she told me. “I was always interested in the most basic of questions: What makes a person tick? How did you become who you became? I wanted to know! Would it help me?”

But that sort of emotional engagement also drew criticism: “I did an interview with Rock Hudson right after his heart attack. He was talking about his feelings of death, and looking out the window and wondering if he’d ever be able to walk the streets or not. It was deep — for him, of all people — to be talking about something like that. When the interview was over, I went to take his hand, and I shook it, and kissed it, and said, ‘Take care, Rock.’ And the TV critic for the LA Times went after me: ‘She wants to be considered a tough reporter and not a gossip columnist! How dare she kiss the hand of Rock Hudson!’”

“And now you notice everyone doing it,” Barrett continued. “Oprah, Barbara!”

Barrett’s success inflamed existing tensions about what the news, including interviews with celebrities, should look and feel like. She had a voice and a style; she wasn’t a fawning groupie, but she didn’t feign objectivity. That attitude alienated newsmen, but it also became the blueprint for today’s “entertainment news,” whether on the morning shows, Ellen, or CNN. She dared to talk about issues that didn’t get discussed on television — she got Raquel Welch to analyze her status as a sex symbol, Richard Dreyfuss to declare that no other man knew what truly meaningful sex was like, and Burt Reynolds to staunchly defend bachelorhood.

She was known to throw curveballs, usually involving something to do with the star’s youth and psychological development that veered from the publicist script. Like the time she interviewed Tom Cruise: “I knew something was slightly wrong. I’d done a ton of research on him,” she told me, picking her words carefully, “which was hard to do, since there wasn’t a lot out on him. But one his friends told me that Tom had been studying for the priesthood.” So once she and Cruise established a rapport, Barrett asked, “What made you want to become a priest?”

“He didn’t know how to answer,” Barrett told me. “And when the interview was over, he went over to his publicist, Pat Kingsley, and said, ‘You must promise me that never again will you allow Rona Barrett to interview me. That woman is a psychologist. I felt like I had been through a session with a doctor.’”

“I think Tom was really scared during that period,” Barrett continued. “That someone would come out and say something. His family was very protective of him, but his mother told me so many things about him over the phone. Never would talk to me again after that!”

That interview happened in the early ’80s — years after Barrett had been invited to become part of a new morning show called Good Morning America, which she helped make a viable contender against the dominance of NBC’s Today show. Bill Paley, then head of CBS, publicly attributed much of GMA’s success to Barrett, but she hungered for more: specifically, an hourlong show, modeled on 60 Minutes, but for entertainment industry news. “Like Entertainment Tonight,” Barrett explained. “But not the way they did it — less fluff.”

She got something like it when she was hired, in 1980, to join Tom Snyder as co-host of the long-running NBC evening talk show Tomorrow. Snyder resented Barrett, and a slew of other retoolings instituted by the network, and feuded viciously with her, refusing to acknowledge her as anything more than a “contributor.” “When the ratings started to go up, he got so jealous,” Barrett told me. “I don’t know that he was on hard drugs, but he was a big drinker, and he said some terrible, terrible things.” But as Barrett explained in 2010, “again, it really had a lot to do with being a woman and Tom being part of the old boys network.”

It was especially difficult to watch as Barbara Walters received the sort of money and airtime Barrett had been working toward for decades. “Barbara was on the Today show after they tried out all those beauty queen co-hosts,” Barrett told me. “And her great success was that she wasn’t Elizabeth Taylor onscreen. She seemed so real.” ABC lured Walters away from NBC with a record-breaking contract; after her own struggle to co-anchor the nightly news with a man, she began hosting 20/20 with Hugh Downs. “But I was doing those deep one-on-one interviews long before,” Barrett clarified. “She started doing them after they brought her to ABC.”

Barrett doesn’t resent Walters, at least not exactly. “That was one of the most hurtful periods of my career,” Barrett said. “ABC’s men couldn’t see two people, two women, who could do something similar, but not really the same, on the same network. So Barbara and 20/20 got the big shot right after Happy Days, and they put me on Saturday nights, where no one had ever succeeded. In the end, it was always about money, and how they were going to protect their million-dollar investment. They had to make her successful. And they did.”

Over the course of the ’80s, Barrett tried other specials, shows, and gigs, including one as a “senior correspondent” for Entertainment Tonight, but none stuck. She was sick of being condescended to — men and women who’d pat her head and say “it’s OK, little Rona” — sick of networks that wouldn’t get behind her desire to do more serious industry reporting, sick of commentary that compared her to Walters.

So Barrett said goodbye. “The day I left Hollywood, I canceled all my subscriptions: Variety, Hollywood Reporter, Ad Age, everything to do with the entertainment industry. I left it all behind. I came up over the pass here to the Santa Ynez Valley, and I thought, Oh my god, this is exactly where I want to be.”

Since then, Barrett has raised horses and grown and sold lavender products — with all proceeds going to her foundation, which has supported seniors in need for over 20 years. But her most recent project is her most ambitious: raising $4.2 million for the Golden Inn & Village — a retirement community for low-income seniors, located in the heart of Santa Ynez, with sprawling views across the surrounding valley.

Barrett’s been hosting galas, filming videos, and crowdfunding a collection of columns on aging, dubbed Gray Matters, in order to rustle up donations. (You can support the project here). When I visited this spring, we watched as they started to drywall the main village (intended for seniors) and the outlying buildings (for low-income families). But she’s still raising funds for a subsidized memory care facility that would provide full-time care for seniors, many of them “orphaned” (without children or relatives), who simply cannot afford services for themselves.

Barrett slowly but fundamentally altered the type of information we consider newsworthy.

But if Barrett’s wistful about what’s become of her legacy, it’s fleeting. “I’d like to be remembered as more of a decent person who really cared about people,” Barrett told me. “The best thing I ever did for myself was to move up here — to taste life in a different way than I had ever known as a child. And I hope others will take a look what we’re trying to do here, with the Golden Inn, and think, We could replicate this in Omaha, or Atlanta, or Idaho. The need is everywhere.”

Today, Barrett feels disconnected from the current state of celebrity — she tried to conjure the name of Celine Dion by describing her as “the girl who just lost her husband, has a big beautiful voice, and works Las Vegas.” But she has a thing for Jennifer Lopez. “I wanna tell you something,” she said, leaning in close. “I just love her new series. I think people have underestimated J.Lo,” she said, looking me straight in the eyes as if defying me to disagree. “I really do.”

Which could also be said for Barrett: Like J.Lo, she persisted despite thinly veiled misogyny, racism, and a general dismissiveness of a certain type of cultural artifact, whether rom-coms or gossip, because people, and women in particular, enjoy consuming it. Barrett slowly but fundamentally altered the type of information we consider newsworthy, blurring the distinction between hard and soft “news” so thoroughly that it’s never been rebuilt.

Barrett’s work was always campy and saucy and just this side of scandalous. But like all gossip, it also sparked conversations — about female sexuality, sexual orientation, AIDS, celebrity drug use, anti-Semitism, and women in power — that the hard news, for all its directness, sometimes cannot.

Barrett fought against those who dismissed her work, on both the personal and industrial level, for decades. Today, dozens of men and women in all corners of the mediascape continue that fight, battling different but not dissimilar forms of insult, devaluation, and sexism. What Barrett, Walters, Nora Ephron, and Connie Chung endured, Katie Couric, Diane Sawyer, Tina Brown, the cast of every female-driven talk show, the vast majority of female sports and education reporters, and everyone who’s written for the Styles section endure.

“I’ve always said that history repeats itself,” Barrett told me, pounding the table a final time with her slight, clenched fist. “It just wears a different dress.” •