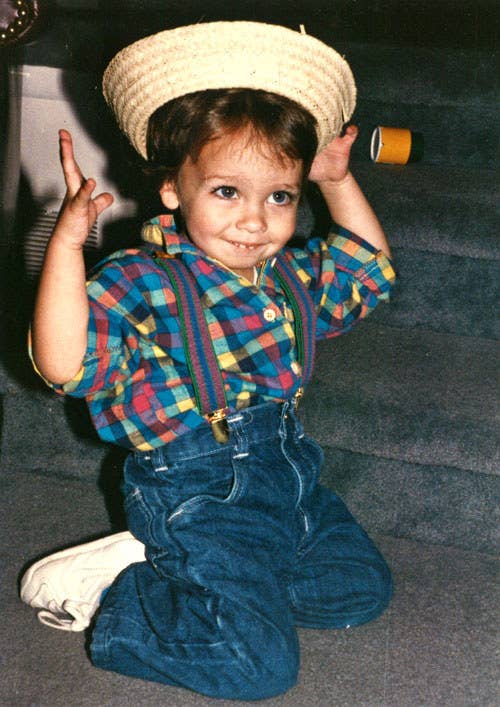

I stopped dead on Broadway, in the middle of the sidewalk, and stared, not up at the beautiful wrought-iron SoHo buildings, as would befit someone who’d moved to New York in the past month, but at an ordinary sign advertising a small clothing shop. The logo, a casual cursive scrawl with both E's capitalized, jumped out at me like a beacon from a lighthouse somewhere deep in the back of my brain. That was the logo emblazoned on my baby clothes, the logo my great-grandfather created. It was, I thought, forgotten family history, the factories having shut down shortly after I was born in the '80s. After a moment I took out my phone and called my mom and asked her what the hell was going on.

She’d heard something about this. Madewell was back, somehow, but she wasn’t sure exactly how or why. I wandered inside the store. It was all women’s clothing — expensive women’s clothing. I found a clerk and said, in some jumbled, excited, confused way, that this was my shop, that Madewell was my family’s business. I think she thought I was angling for a discount. After politely and professionally feigning interest while I struggled to explain a history I didn’t even really know, the clerk stopped me. “We don’t sell men’s clothes,” she said.

Over the next four years, I saw Madewell everywhere. Today there are three stores in Manhattan alone, and 77 throughout the country. On bags on the subway, on tags of clothes worn by friends, I am constantly bombarded with totems of my family history.

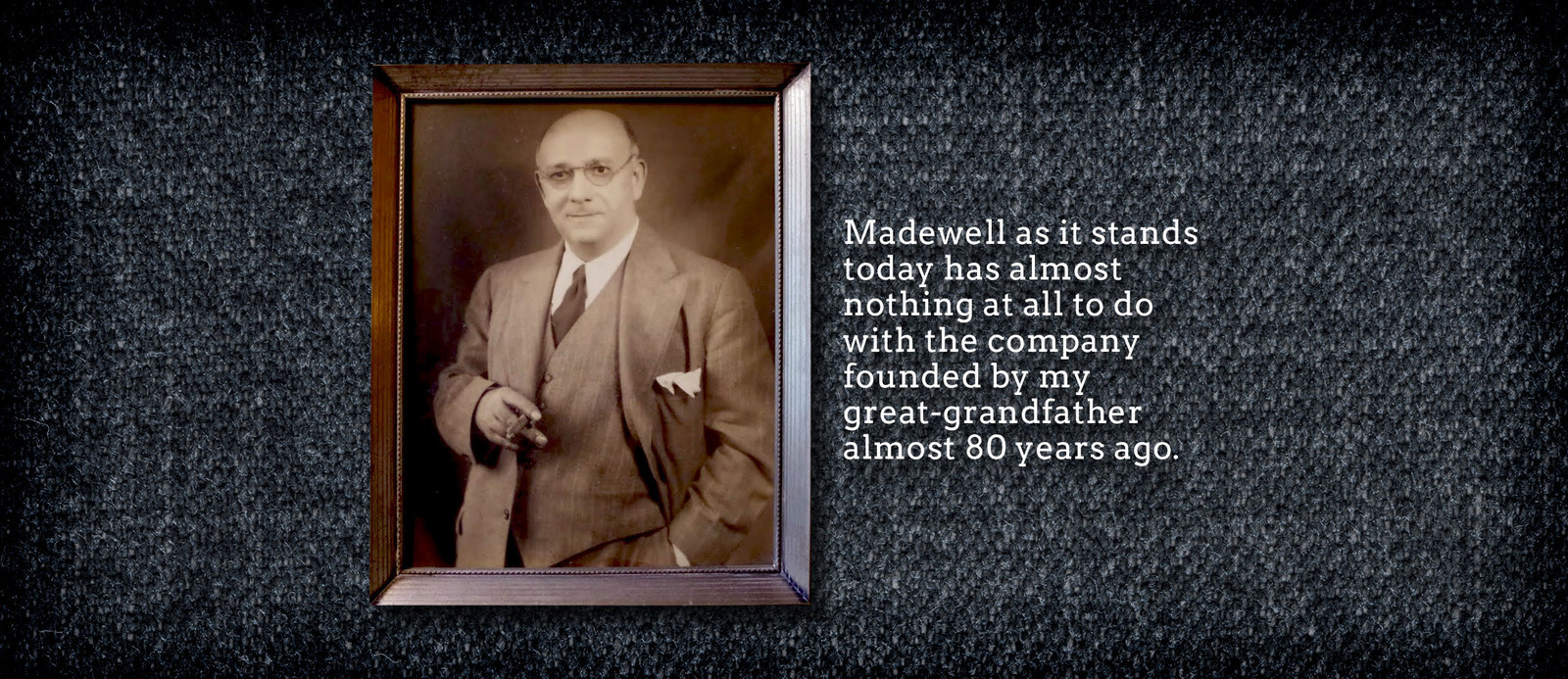

Asking my family yielded the basics: Madewell as it stands today began in 2004. That's when Millard "Mickey" Drexler, now the CEO of J.Crew, acquired the logo and the trademark of the company my great-grandfather founded in 1937. Dhani Mau, a senior editor at Fashionista, said, “J.Crew considers it their younger sister brand,” though she said it’s not necessarily for younger sisters. Pressed to pick out a celebrity who might typify the Madewell girl, Mau chose Kate Bosworth and Rachel Bilson. This does not entirely jibe with my mental picture of my tough immigrant great-grandfather selling stiff denim overalls to New England dockworkers.

Still, Madewell will not let you forget the date 1937. The store could originally be found online at madewell1937.com, and the year is prominent on the site and on some of the clothing. The company's Instagram and Twitter handles are both still @Madewell1937, and its LinkedIn page says, "Madewell was started in 1937 as a workwear company, and we're always looking to the brand's roots for inspiration."

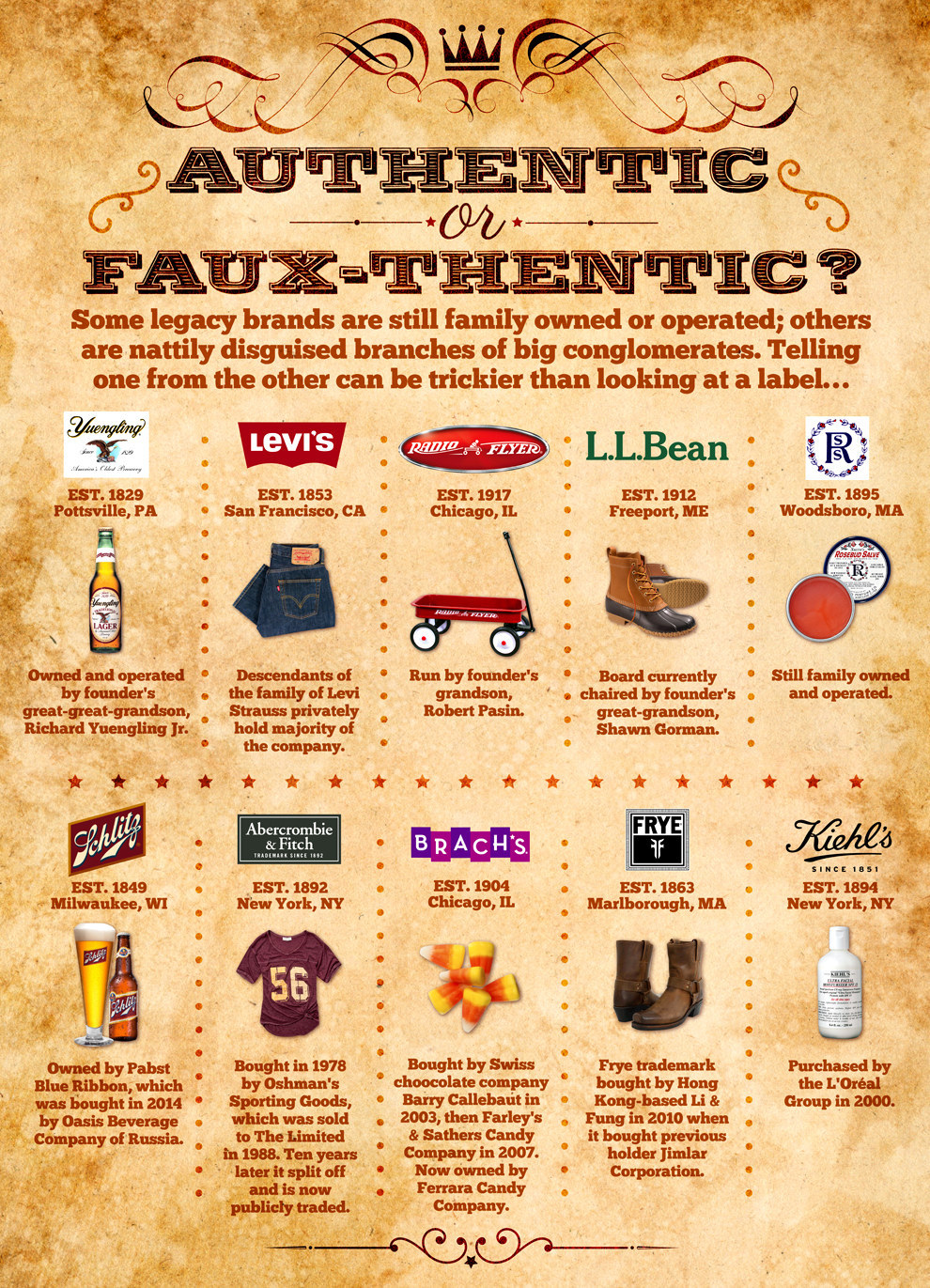

This is, to put it mildly, baloney. Madewell as it stands today has almost nothing at all to do with the company founded by my great-grandfather almost 80 years ago. How many vintage labels out there have similar stories? How many corporations are out there rifling through the defunct brands of America’s past like a bin of used records, looking for something, anything, that will give them that soft Edison-bulb glow of authenticity?

Madewell’s story — my story — leading up to that moment in SoHo began over a century ago, half a world away. It traces the evolution of how Americans shop, and how Americans shop heavily informs how Americans see themselves; we, as a country, are what we buy. Mickey Drexler, in creating J.Crew’s new womenswear stores, shrewdly read the market and realized that stocking nice clothes wouldn’t be enough: He’d have to tell a story along with them. Drexler didn’t have any stories, so he bought ours.

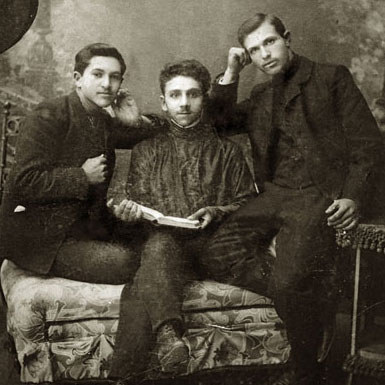

Julius Kivowitz was born in Russia in 1889 or thereabouts. His name was not Julius Kivowitz at the time — it was Beham.

At the turn of the century, the Russian Empire required that all males, starting at age 20, serve in the army, and Julius seemed to be not very taken with this prospect. The Beham family was fairly well-off and managed to secure a sponsor for Julius in the U.S., in a prosperous Massachusetts port city near Providence called New Bedford. There was only one problem: Any attempt by Julius to leave under his own name would have exposed him as a draft dodger. (Some in my family, including his youngest daughter, referred to him as a "conscientious objector." Whether he objected to war or merely his own participation in the war isn't clear.) My cousin Judy told me that Julius invented his new last name by going to a cemetery and picking out the name of someone who, had he lived, would have been about the same age.

It was a good time for a Jew to leave Europe. By 1906, pogroms — huge, brutal, bloodthirsty, anti-Jewish riots — were commonplace in the Russian Empire. Mobs of Russians burned and sacked entire Jewish towns, murdering men, women, and children, with the implicit permission or even participation of police. Many Jews fled, the newly renamed Julius Kivowitz and his fiancée, Fannie, among them. (It was somewhat scandalous and also a bit romantic that the two fled together before they were married.) He landed at Ellis Island at age 19, stayed in New York for a few years, moved north to Connecticut, and then went further eastward up the Atlantic coast to New Bedford.

When my great-grandfather arrived there some 90 years ago, New Bedford was just beginning the decline from its status as one of the country’s most bustling, wealthiest port cities. New Bedford had been the whaling capital of the world, one of the settings in Herman Melville's Moby-Dick. Hundreds of huge, magnificent schooners and clipper ships were built and launched from its port. By 1850, thanks mostly to profits from whale oil, New Bedford was the wealthiest city per capita in the country. But the whale oil industry collapsed, and by the time the wave of immigrants that included my great-grandfather and his young family settled there in the 1920s, the town had pretty much abandoned whaling and turned to fishing and manufacturing.

Julius, like so many of his generation of immigrant Eastern European Jews, was an entrepreneur with no particular passion besides financial success. First he opened a grocery store, earning enough money to, along with a partner from New York, move into textiles. It was a natural move for Julius, as it was for many other Jews, who brought a centuries-long tradition of textile manufacturing with them from Europe. Beginning around the 16th century in Eastern Europe, Russian and Polish Jews began working with wool. By the 1860s, heavily Jewish cities like Lodz and Bialystok were textile-manufacturing centers; more than half of the textile industry in Bialystock was Jewish-owned. This was pretty much stamped out by the 1930s, thanks to decades of violent anti-Semitism perpetrated by independent Poland. But Julius had already fled Eastern Europe and made his home in New Bedford.

In 1936, Julius filed for the Madewell trademark, and in 1937 he opened his first factory. No one seems to know why he picked — or if he himself even did pick — that name. But I don’t think his English was ever all that good, and there’s something very clean and utilitarian about it.

There is nobody alive who remembers the earliest chapters of Madewell. The only one of Julius' children still living is my great-aunt Barbara, the youngest of the Kivowitz brood by nine years. Her husband, Aaron, ran the shipping department of Madewell, but didn't come on until 1951. Nobody knows much about that mysterious New York partner who oversaw the factory floor but vanished from the company within a few decades. Nobody knows how many workers — "stitchers," they were called — were employed at first. Nobody, to be frank, seems to know much about Julius. The documents I could find from that era give the date of the company’s founding but not much else; whatever records Madewell kept from its early years are gone. After questioning damn near everybody still alive who ever met him, here are the facts I gathered about my great-grandfather:

1. He spoke mostly a mix of Yiddish, Russian, and English, with a thick accent.

2. He was rarely seen without a cigar.

3. He loved the card game pinochle, and played every week.

4. He didn’t talk much, and I can find exactly no one who can recall him saying a single word about his childhood in Russia.

5. He liked nice things. He built a big house and filled it with expensive appliances and Oriental rugs, which seems to have annoyed his wife Fannie, who did not care much for extravagance.

That's it.

His employees at the time likely included the dominant immigrant groups of New Bedford: Portuguese speakers largely from the Azores and Cape Verde, French Canadians, and possibly some Jews. The company at the onset was designed smartly and specifically to cater to the substantial working class of the community: It made jeans, dungarees (which differ from jeans in that the threads are pre-dyed before weaving), and bib overalls. These were hardy work clothes, intended for use inside the factories and fisheries of New England.

Madewell was a family operation. Julius' son Haskell and his sons-in-law Aaron and Jerry ran departments (sales, shipping, and manufacturing, respectively) within the company. Various cousins and nephews and nieces and grandchildren worked there during summer vacations from school. Gradually, as Haskell took a larger role in the company, Madewell branched out into other clothes.

By the early 1960s, Haskell's strategy to diversify Madewell’s offerings (and to sell to larger department and discount stores) had kicked into high gear, as it began to make children's and women's clothes. It’s sort of hard to get a sense of what Madewell really was at the time — my great-grandfather had to be cajoled and sometimes tricked into allowing his company to change, but the company seemed built to adapt pragmatically to each era.

The company didn't have any particular aesthetic. Most of the clothes were contracted, made by any of several other factories and stamped with the Madewell name. Madewell had lots of partners at other factories — one in Georgia, one in Kentucky, among others — that would take care of the design and manufacturing. If Haskell or Jerry or Julius went to a local department store and saw that corduroy-lined denim jackets were selling well, they'd come back to the factory and tell one of the stitchers to make one. If the stitcher wasn't sure how, they'd buy one of those jackets, tear it apart, and make a pattern out of it, then re-create it. Or if that seemed like too much trouble, they'd call one of their contacts at another factory, say, "Make us a corduroy-lined jacket," stamp their logo on it, and sell that. Madewell’s logo didn’t necessarily indicate who physically created the garment, but simply who was selling it.

"We didn't do too much of that designing bullshit," my great-uncle Aaron told me. Aaron is a warm, tough, stocky man whose crushing handshake hasn’t lessened in strength even as he ages into his eighties. As we talked at his kitchen table, looking out on wild turkeys strutting through his backyard in Dartmouth, Massachusetts, he would occasionally sing what I think is a line from “Memory,” from the musical Cats. "The only stuff we did in-house was the rough stuff,” he said. “Denim, brown duck pants, carpenter stuff." During Aaron's tenure, there were only ever around 25 stitchers at Madewell who actually made clothes. I asked Aaron who designed that stuff. "You copy somebody else's!" he laughed. "Come on, 'design.' It was not a fancy place, Dan. No such thing as 'designing.'"

Aaron bristled when I asked if the Madewell clothes were high quality — "Oh, yes, they were very well made," he said — but these weren't exactly pioneering designers crafting original clothing out of a deep passion. They weren't inventors or artists. They looked at what was selling and made some of that to sell. It was a business, and Madewell did what made sense from a business perspective. J.Crew’s Madewell is grasping to emulate some sepia-hued commitment to quality in the original company, some moral or ethical standard from better, more authentic times. But that’s not what motivated my great-grandfather at all — his motivation was profit, and quality was a means to an end.

New Bedford is one of the last towns you pass through as you drive eastward out to Cape Cod, which hooks out from the East Coast like a flexed arm. It’s located on the coast of Buzzards Bay, which carves a messy notch into the underside of Massachusetts. It would be uncharitable, but not inaccurate, to say that New Bedford is the armpit of Massachusetts.

Despite a cute, gentrified waterfront area and a few museums, the city is today one of the poorest and most dangerous in the state. Big brick factories, either barely used or totally vacant, are everywhere; the unemployment rate hovers above 10%. In the 1990s, the city attempted to rename the area the “South Coast,” because merely the name of New Bedford signifies decay, depression, and loss.

And still, New Bedford looks like a port city in the way that only New England towns can. Trim three- and four-story houses, mostly in sea-weathered gray, line the streets. Every turn seemingly leads to the water, the smell of which is everywhere. Huge stone levees, looking like the organized results of avalanches, do their best to protect the city from the Atlantic's wrath, and roads that cut through these levees are equipped with alarmingly heavy-duty iron gates, up to 20 feet high, that can close if water approaches.

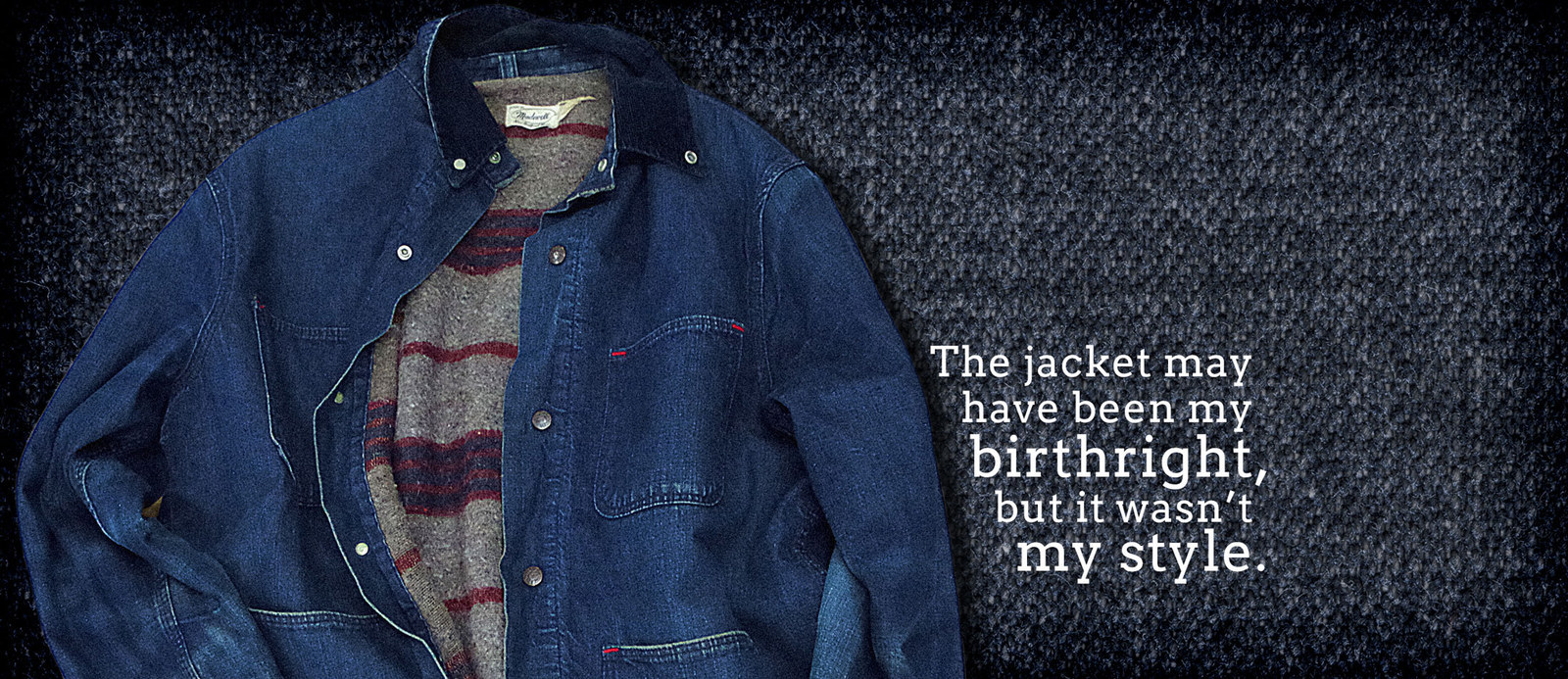

Circa Vintage Wear on 73 Cove St. is airy and industrial, still chilly in the Massachusetts spring. The medium-size, mostly unmarked brick factory, just beside the ocean, smelled of old fabric and dust and wood shavings, a pleasant perfume that changes subtly as you move through the decades upon decades of vintage clothing and accessories. In one corner, a wall of nothing but circular hatboxes reached to the high ceiling. A twentysomething who would later buy a pair of shiny gold dress shoes examined an entire case of bow ties. Semi-broken old mannequins wearing everything from frilly white gowns to what looked like old high school marching band uniforms stood sentry in aisles of clothes from wildly disparate eras. In the racks, jammed up against what must have been dozens of other stories just as rich and as weird as mine, were a few pieces of original Madewell.

There were heavy-duty jumpsuits, which must have dated from the 1940s or 1950s. There was a denim jacket with a striped, sweater-like lining and a corduroy collar. There was a pair of Dickies-like blue chino work pants. There was a pair of bell-bottoms from the 1970s that could have been made by Levi's or Wrangler or lots of other big international brands — but the bell-bottoms, the jumpsuits, the jacket, and the work pants all boasted that label, that great logo, that stopped me dead in my tracks in New York years before.

Chris Duval opened Circa in 1986 and has been pretty much its sole employee ever since. Wearing a pale denim jacket and tough denim work pants, Duval is short and slender and speaks with a thick South Coast accent, which is somewhere between Boston and cartoon pirate, and all of his statements sound like they should end with an exclamation point. He told me that he likes to sit down with the people from whom he buys his wares and learn about the history of each piece.

"When this whole thing came about with J.Crew, I was devastated," he said, in the same tone that a fan of an indie band might have bemoaned signing to a major label in 1995. "When that happened, workwear was just coming back. So I thought, Oh, cool, they're gonna do a workwear line inspired by Madewell. But it has nothing to do with that! It's Chinese crap!"

Duval found the way J.Crew touted its connection to the original Madewell especially galling. "You go to the flagship store in New York and there's a big thing about New Bedford and its heritage, and I'm like, Oh, god, this is so sad!" Duval told me that he liked to put pictures of his original Madewell goods on Instagram and taunt J.Crew about its "Madewell in name only" clothes. "They're using the original brand to push something that has nothing to do with the original brand," he said.

I looked more closely at the flannel-lined denim jacket. It was cool, and vintage, and, being that my great-grandfather’s company made it, I’d have a great story behind it. I tried it on and immediately took it off. I looked like I was wearing a costume. I hadn’t realized how reliant my taste in clothes is on modern shapes; I didn’t at all care for the boxy, un-tailored fit of the jacket, the baggy sleeves, or the too-smooth washed denim. The jacket may have been my birthright, but it wasn’t my style.

By the time I left New Bedford, it was clear that I had a different reaction to the staged authenticity of J.Crew’s Madewell than Chris Duval did. I almost envied his clear-cut offense at the company, but I was surprised to find that I didn’t really share it.

The concept of authenticity in retail is a borderland where academics and marketers commingle. It is a philosophical chew toy that is also the key to fleecing consumers in new, exciting, and highly profitable ways. Jim Gilmore, the co-author (with B. Joseph Pine II) of Authenticity: What Consumers Really Want, knows this better than most. His book doesn't so much offer tips to marketers as it examines what authenticity means in a retail space, and how customers react to it.

According to Gilmore, the American consumer economy has moved through three distinct stages, from agrarian to industrial to service, to arrive at what he terms in his book the “experience” stage. To sell a product today, a company must also sell a story, a transformation. A new pickle company needing to differentiate itself can’t simply rely on people needing to eat (agrarian), or undercutting the competition on price (industrial) or convenience (service). The way to sell that jar of pickles is to tell consumers about how it's an old-country recipe from the Romanian hills, using heirloom cucumbers grown upstate and fresh dill from the factory's rooftop garden, and it was crafted only two miles from here in a facility that used to make No. 3 pencils.

"We define authenticity," Gilmore told me over the phone, "as purchasing on the basis of conforming to self-image. 'I like that, I am like that.'" Authenticity is about buying into a product that confirms what you already think, or want to think, about yourself. Of course things like quality and durability are all mixed up in that; the Romanian-Brooklyn pickles are, probably, pretty good, and the fact that the buyer wants to see himself as the type of person who buys cool weird pickles doesn't negate the fact that the buyer may also recognize that the pickles are better than Claussen's. In fact, that’s part of it: Self-awareness of the purchase is key to the purchase itself.

In his job as a marketing consultant, Gilmore sometimes takes clients on tours of stores he deems worthy of emulation. He remembers when he first saw Madewell: "It feels like a boutique store while surrounded by boutique stores in SoHo, but it's not one," he told me. "The place has got integrity; it all holds together.” He praised the choice of materials and fixtures ("industrial without being too raw," he said). He also praised the choice to show a select line of clothes, with limited quantities of each. This is, of course, common in boutiques, which are able to produce only in smaller quantities for cost reasons. For Madewell, it's an aesthetic choice. Madewell has 77 branches in the U.S. at the time of writing, including stores in the two largest malls in the country, the Mall of America in Minnesota and the King of Prussia Mall in suburban Philadelphia. Madewell doesn’t have any trouble stocking its shelves. It’s telling a story about itself, that it’s a small, lovingly curated boutique. This isn’t true at all, but the customers don’t much care. Madewell's unlikely rebirth, however, began with a man who had no interest in blurring these lines.

“I had always been a big fan of Madewell and was trying to buy or license the name,” David Mullen, a clothing designer who now runs a few shops called Save Khaki, told me over the phone. “I would find the label at vintage stores and I loved the way that it looked, and the name itself, what it represented." Mullen made trips up to New Bedford to learn more about Madewell, making some of the same stops I made, and for some of the same reasons: What was this company? What did it make and why?

But Mullen had a larger idea: He wanted to relaunch Madewell. “I wanted to do a modern take on workwear, and I wanted it to be kind of androgynous,” he told me. In his consulting work, he’d become friends with Millard “Mickey” Drexler, and he brought this idea to him. Together, the two began figuring out how to resurrect Madewell from the dead.

Drexler is a huge name in the retail world; he has been the subject of numerous stories and television segments that harp on his uncanny knack for selling things to Americans. He led Gap through its 1990s boom, taking the company from, as a 2010 New Yorker profile by Nick Paumgarten put it, “a shaggy little jeans chain to a gigantic but fairly nimble purveyor of the stuff everyone wears.” Called by some in the industry “the Merchant Prince,” Drexler was ousted in 2002 during a downturn in Gap’s earnings, and the following year ended up as the chairman and CEO of J.Crew Group Inc. (Madewell declined my request for an interview with Drexler.)

During those few months, he and Mullen tried to work together on Madewell, but it didn’t quite work out. “We kind of made the Madewell thing together, then he put it on hold because he'd just taken the J.Crew job, and that was a pretty big job,” said Mullen. “So I helped him a bit with that and then decided to go off on my own.” Mullen now has no part in Madewell at all, but he says there’s no ill will, and speaks highly of Drexler. “It was more of a timing issue. I was anxious to start something, and it was easier to start something on my own.”

Mullen, according to U.S. Patent and Trademark Office paperwork, paid $125,000 for that logo and trademark, and nothing else, signing the papers on Jan. 31, 2003; the factories had been closed for nearly 15 years at that point, so there wasn’t really much to sell. (For the sake of disclosure, neither I nor anyone in my immediate family received any of that money.) According to Mullen, my great-uncle Haskell’s son Jay Kivowitz set up the sale and kept the earnings, as Haskell died shortly afterward. Jay refused to tell me anything specific about the sale. It’s a sore spot within the family, though certainly he had the legal right to keep it; he was the sole owner of the company at that point.

On April 14, 2004, Mullen transferred the trademark he’d gotten from my family over to Drexler. Curiously, the document shows no money trading hands. Mullen, when pressed, said only, “Mickey’s a very fair guy,” but would not tell me anything further about their agreement besides that he now has no stake whatsoever in Madewell. By then, Drexler was established as the chairman and CEO of J.Crew, and leased the Madewell trademark (as Millard S. Drexler Inc.) to J.Crew Group Inc. for a dollar a year.

Mullen's current operation, Save Khaki has only three small boutiques, all in New York City, and sells only a few products, very carefully designed and chosen. Mullen gushed when talking about his design process; he tried repeatedly to get access to Madewell’s old factory just to look at whatever detritus was left there since it shut down in the 1980s. “I thought there must be all old kinds of patterns in there, ribbons and buttons and ... to me that would be priceless,” he said. Save Khaki's clothes, too, are all made in the U.S. — some even come from factories in New England, including one in Fall River, the sister town to New Bedford where my mom grew up. The modern Madewell isn’t run in quite the same way — much of the clothing is manufactured overseas, although some of the denim is sourced and produced in the U.S.

“A merchant is someone who figures out how to select, how to smell, how to identify, how to feel, how to time, how to buy, how to sell, and how to hopefully have two plus two equal six,” Drexler told the New Yorker. As presented there, he is a fluid and reactive figure whose personal tastes and interests and philosophies are irrelevant. This is evidenced by his success with both Gap, a company that unapologetically boomed during the prosperous Clinton era with enormous stores full of casual, affordable clothes, and Madewell, which sells, for example, this insane JNCO-looking pair of Rachel Comey-designed pants for $426.

Somsack Sikhounmuong, the current head of design for Madewell, is mild-mannered with soft eyes and a trim beard. I asked him what he knew about the original Madewell besides the fact that it made jeans. He told me he knew it was a New England-based workwear company, but that was about it. I asked how, if at all, the J.Crew Madewell connects to the original. He hesitated, stumbled over his words a bit, and said that J.Crew isn’t trying to reproduce the original Madewell’s style, that the connection is more broad.

"There's a heritage to it, a real appreciation for the past and for real things," he said. He sees this in its design aesthetic, but only in a thematic, rather than specific, way: "Not too trendy, not too fast fashion." Trendy, to Sikhounmuong, means "colors are very bright, patterns are really crazy." Madewell is certainly not that; it runs to jeans, boyish button-down shirts, A-line dresses, that kind of thing. Nothing is neon, hardly anything has visible logos or words or pictures, and where there are patterns, they are classics: stripes or polka dots or plaid. To Sikhounmuong, these elements are outside of trends; they are the standards.

"I don’t want this stuff to be disposable,” he said. “I want this piece to be relevant five years from now, that you can still pull it out of your closet." Part of that intended timelessness, reflected from the name and logo, appears in the price of the clothing.

A lot of the products and shops that have come out of the capitalist embrace of authenticity and vintage are silly and fake, but the thing is, if you're really going to ape a cultural movement, you have to go all in. Part of the cultural change that spawned Madewell is that being older and more honest and taking the time and making a better product is, well, better. There is much to be scornful of in this world of Mason-jar salads and twirly mustaches, but a major, and admirable, tenet of this specific modern twist on consumer culture is the idea that it is better to do things the right way. It is better to make fewer things than more things, because you can concentrate on those fewer things. This is why Americans of a certain age and class are more impressed by a pizza place that serves nothing but margherita pizza than by Domino's, which sells a million combinations of cheese and sauce and bread and meat and will deliver to your door in 30 minutes or less.

This is not exactly what Madewell is doing, of course, but it is certainly what it is attempting to appear to do. Any veneer of authenticity or oldness is necessarily diffused, not specific, but we’re OK with that, in part because we like the aesthetic and in part because the stuff really is pretty high quality.

Most of my interview with Sikhounmuong, which was conducted in a conference room accompanied by two public relations people, was friendly. But eventually I had to ask: Didn’t he think it was, somehow and in some way, wrong to insinuate that Madewell today has any connection to my family's company? Wasn’t that misleading and just a little bit gross? Sikhounmuong hesitated and looked to the PR person sitting next to him. This wasn't really his game: He doesn’t craft slogans; he designs clothes. Eventually he said, "I think it's an aspirational slogan. It says we know this name is a great name and we know this brand is a great brand. That's what I take from it."

That's not what I take from it. What I've taken from it is that my family's company probably gave even less of a shit than Madewell does about quality and design and passion. Its clothes were as high quality as they could afford because it was in their best interest to make clothes people were satisfied with. They manufactured in the U.S. because at the time it was cheaper to do so, and because it was easier. They weren't noble; companies back then didn’t construct a facade of nobility and purpose. This was a company founded by a Russian immigrant who was probably an identity thief, a company that regularly stole the intellectual property of competitors if it thought it would sell. Both of the companies named Madewell adhere to the way things were done in their respective times. We look at the past through glasses that bring into focus only what we want, and need, to see; they distort everything else.

My great-uncle Aaron didn't recognize anything on the Madewell website. And I think he would probably look at the exposed brick in a Madewell store and wonder why they didn't finish putting up the walls. If Julius were alive, I think he’d be very impressed that a company called Madewell posted revenue of over $180 million in the fiscal year 2013. He would care not at all about whether it was authentic, or what the word “authentic” even means.