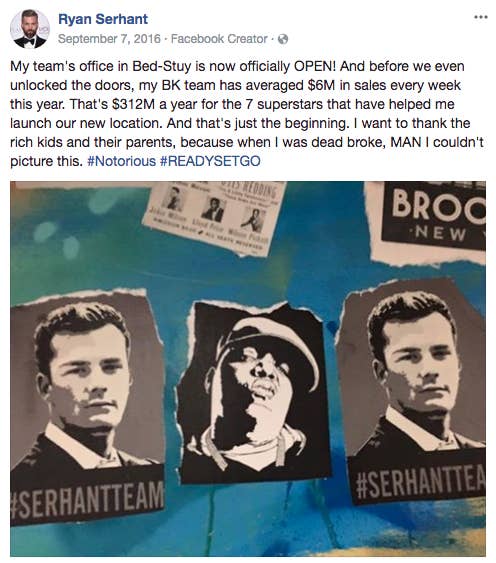

Ryan Serhant, New York City’s self-described “#1 Broker,” is on a roll. Since we left him at the end of last year's season, the star of the hit reality TV show Million Dollar Listing New York got married on a Greek island. He landed a new show, Sell It Like Serhant, in which Bravo promises he will transform floundering brokers into selling sharks. And he opened a new Nest Seekers office in Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, planting his flag in one of the hottest housing markets in the country. He announced his arrival on social media with a photo of himself alongside Bed-Stuy–born rapper Biggie Smalls. Thanking his Brooklyn team and the “rich kids and their parents” that helped get him here, he cribbed a line from “Juicy,” Biggie’s ode to his own meteoric rise: “When I was dead broke, MAN I couldn't picture this.”

Over the last decade, Serhant has ridden the real estate market from its nadir to its peak. In 2006, he arrived in New York, an aspiring actor. He made it one season as a homicidal biochemist on As The World Turns before he was killed off with a syringe to the heart. Serhant says he never wanted to become a broker. But after a short stint as a hand model, he caved and applied for his license. He started on Sept. 15, 2008, the day that Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy. It was the start of a global economic crisis. He had nowhere to go but up, and up he went.

Serhant moved from rentals to high-end sales. Then he landed a spot on Million Dollar Listing in 2012. Three years and two Emmy nominations later, he was named one of the city’s top brokers. Ryan Serhant is now a brand, complete with more than 675,000 Instagram followers.

In the latest season of Million Dollar Listing this summer, Serhant’s ardent fans saw him stamp that brand on Bed-Stuy. Its May premiere showed him in the back of a car, newly bearded and sporting a leather bomber jacket. Next to him was Brett Wexler, a lawyer representing a group of investors with 100 properties in Bed-Stuy and nearby Bushwick, two historically low-income black and Latino neighborhoods fast becoming part of the country’s hottest property markets.

They drive down brownstone-lined blocks, where Wexler gives Serhant the lay of the land. “We purchased all these homes from previous owners during the recession period,” he tells Serhant. Now they want them sold. “We’re hoping you’re the guy to do it.”

Wexler drags a quickly bored Serhant on a “six-hour listing marathon.” Serhant’s head lolls as the camera cuts to one renovated house after the next. But he can do the math. “What’s 3% of $200 million?” On the bottom of the screen pops his potential commission: $6 million. For that, he says, “I will sit in a car all fucking day. And I’ve done a lot worse things for listings before.” Ryan Serhant was in.

What Million Dollar Listing’s viewers did not learn, and what Serhant told BuzzFeed News he did not know, is that before the fresh paint and white Carrara marble, these houses were teetering on the edge of foreclosure.

Their transformation into reality TV dream homes played into a growing crisis in affordable housing, with vulnerable New Yorkers losing their grip on homeownership just as the value of their homes is skyrocketing.

“It’s a land grab,” said Catherine Isobe, an attorney at Brooklyn Legal Services. “It’s a big wealth transfer from people of color who scraped and saved to get these houses when no one wanted to live in these houses, to the white people who now want to move in.”

When one looks at the fallout of the Great Recession, “the winners and losers are clear,” said Josh Zinner, who founded one of New York City’s first foreclosure aid projects in the 1990s. It was particularly devastating for black families, who, nationally, lost half of their collective wealth. “It was whole communities that were destroyed.”

The story of how the homes of poor and working-class Brooklyn families ended up in the hands of one of reality TV's favorite high-end real estate brokers is a story about those winners and losers. While the reality TV version of this story has its own dramatic ups and downs, the real-life backstory is a truer, messier tale. It’s one in which decades of housing discrimination and unscrupulous lending devastated black and Latino homeowners, even whole communities, and paved the way for a sea change in American homeownership.

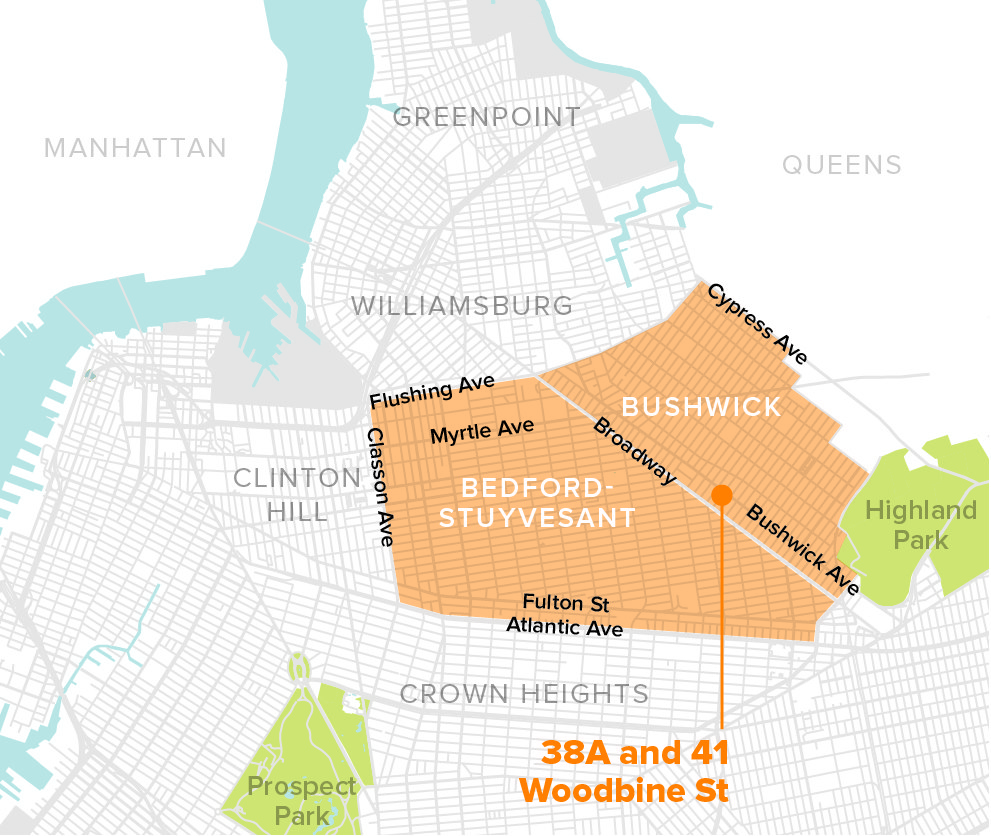

It’s a story about who gets to live out the American dream of homeownership and who has learned to profit from it. It begins with two, low-slung houses on Woodbine Street in Bushwick, and the tough, generous woman they once belonged to. Her name was Gladis Dugue.

Woodbine Street has always been a place of in-betweens. “They call this block a little piece of heaven and hell,” said Linda, who has, for 25 years, lived on this quiet block on the border of Bushwick and Bed-Stuy. A cluster of boxy row houses huddle at one end of the block. Some have fresh faces, their wooden fronts plastered over white, blue, and brown. They rub shoulders with their former selves, aluminum-sided houses like Linda’s, with plastic awnings that sit like a cap over their front doors. A new coffee shop nearby sells lattes and hibiscus-flavored donuts. Around the corner, the local food pantry hands out canned goods. On one end of the block, an empty lot collects discarded grocery bags. On the other sits 41 Woodbine St.

The first time Evan Padget saw 41 Woodbine in May 2016, it was a shell, stripped to its studs. Padget and his wife had recently moved to the city from Colorado and wanted to buy. They looked first at 38A, a newly renovated house. It sold before they could make an offer. One of the brokers on Serhant’s team told them they had another property across the street. He toured the couple through the skeleton of 41, helping them imagine what the house could be. They were excited by the prospect of choosing lights and finishes, and aware that prices were rising fast. They bought the three-story house, with its four bedrooms and a wrought-iron fence, for $1.3 million.

The knocks on the door started not long after they moved in that summer. Strangers asked about relatives or friends they said had recently resided in the house. When Padget explained he was the new owner, they asked for forwarding addresses. He had none to give. Mail began arriving — notices from collections agencies, letters to something called the “House of Hope,” and, strangest of all, boxes of Christian literature that a white van dropped off every third month. He started to wonder about the history of the house.

On Google and in public records, he found a name: Gladis Dugue. Longtime neighbors told him Dugue’s family had lived there for many years. She had a storefront church, and ran 41 and 38A as private shelters for the addicted and mentally ill. But they didn’t call her Gladis. To them, she was Apostle Dugue.

Dugue was not yet 20 when she left Orangeburg, South Carolina, with two young sons in tow and dreams of being a singer. She arrived in New York in the mid-1950s, on the tail end of the Great Migration, when thousands of black South Carolinians went north. As her children remember it, Dugue left because her children’s father fell through on his promise to marry her, and because her own father worried that in the Jim Crow South, the way his daughter spoke her mind might just get her killed.

The Brooklyn in which she settled was undergoing a radical shift. White residents were moving to the suburbs thanks to federally subsidized mortgages created to help them realize the American dream. Black and Puerto Rican newcomers took their place. Stoking racially tinged anxieties of imminent market decline, “blockbuster” developers would leave calling cards in the mailboxes of white homeowners in Bushwick that read “Don’t wait until it’s too late.” Many sold cheap and ran.

Across the city, neighborhoods with large black populations declined precipitously. Starting in the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration designated nonwhite neighborhoods as “hazardous” for lending and refused to insure mortgages there — a practice that came to be known as redlining. In Bed-Stuy, “obtaining a legitimate mortgage became a kind of underground enterprise like locating a bookmaker,” Milton Galamison, a civil rights leader and prominent minister, wrote in 1963. While redlining had officially ended by the late 1970s, decades of discrimination and disinvestment left their mark. In 1977, a citywide blackout triggered arson and looting that left Bushwick looking like a war zone.

In the mid-1960s, one notorious blockbuster, later convicted of bribery, bought 41 Woodbine St., selling it to the man who would, in 1979, sell it to Dugue. She was by then a seamstress and mother of four living in a neighborhood that had become synonymous with the blight and disinvestment engulfing the city. Exactly how Dugue paid for it her children do not know, but her daughter Doris Gadsden-Andrews told BuzzFeed News she was almost sure it was not with a traditional loan.

“You would not have been a homeowner in the Northwest Bronx, Morrisania, East New York, Bushwick or Harlem in 1978 and been able to get a loan,” said Jerilyn Perine, executive director of the Citizens Housing and Planning Council, who served as the city’s housing and preservation commissioner from 2000 to 2004. “Look at it from a lender's point of view — bombed out, rampant with crime — why would you make a loan there? It would not have seemed like a wise investment.”

Around the time Dugue bought 41 Woodbine, homelessness and hunger, then crack cocaine, were spreading through Bushwick. A deeply religious woman, Dugue started a ministry, the House of Hope. She fed people as she preached to them. Then she let them move in. When her eye settled on people in need — the destitute, but also the mentally ill and addicted, the abused and the felonious — Apostle Dugue opened the door to 41 Woodbine. In the mid-1980s, she borrowed $41,000 from a lender called Metrofund Ltd., which her children said she used to buy a second house across the street. Women lived in 38A. Men lived below her family in 41.

Dugue would be applauded by the local police precinct for giving shelter to those in need, but the loans she took out left her with a precarious grip on the houses. Metrofund was among a new kind of lender that sprang up after federal regulators loosened lending standards. Arriving in neighborhoods like Bushwick in the 1980s, these institutions courted borrowers with less than pristine credit and little money in the bank. “We help people the banks turn down,” Metrofund president Robert M. Grossman told the New York Times in 1983.

By 1994, “subprime” lending was already a $35 billion business. Five years later, it had ballooned to $160 billion, concentrated in the credit-starved black neighborhoods of South Los Angeles, Chicago, Baltimore, and Brooklyn. When those loans started to go bad, they triggered foreclosures like those that hit the nation less than a decade later. America’s mortgage meltdown “was a crisis that started with black and brown neighborhoods,” said Desiree Fields, an urban geographer at the University of Sheffield, in an interview. “It was not necessarily perceived as a national crisis until it began to affect more middle class, more white, in our imagination, ‘suburban’ homeowners.”

Over the next decade, Dugue and her neighbors grasped at imperfect solutions to hold onto their homes. Some refinanced a second, third, fourth time, sinking deeper into debt. Some saw their homes foreclosed upon and quickly snapped up by speculators. Others, including Dugue, got entangled in complex “foreclosure rescue” and “home saving” schemes offered up by predators who targeted owners trying to hang on.

It’s the bank’s job to say, ‘this is all I will lend you, because this this is all you can pay.’

“You have this community that’s kind of isolated from the larger world economically — whatever resources are available to them, they husband,” said Hilary Botein, a professor and public policy expert at Baruch College who has studied lending in Brooklyn. Lucrative to the realtors and lawyers orchestrating them, these deals often proved disastrous for homeowners.

At the height of the subprime frenzy, Dugue took out her last round of mortgages.

By then, Wall Street’s growing appetite for debt that could be packaged and sold as investment products led brokers to write loans without proof of a borrower’s income or assets. Those loans would soon prove instrumental in sinking the US economy.

“Though nobody in this whole horrible story is completely innocent, to me, the lenders bear the bulk of the blame,” said Harold Shultz, an attorney and former deputy director of the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. “Borrowers always want more money. It’s the bank’s job to say, ‘this is all I will lend you, because this this is all you can pay.’

"The banks acted irresponsibly by giving loans that were unsupportable. The reason that they did it is we had evolved a system in which the bank did not bear the risk of the loans not being paid back,” he said. Because they planned to bundle the loans and sell them on to third-party financial institutions, “they did not care.”

In 2005, Dugue was issued two loans totaling more than $740,000 from Fairmont Funding, a Brooklyn-based mortgage lender that did a brisk business during this era, and which shuttered soon after the crash. By 2009, Dugue had defaulted on both.

It wasn’t until soon before Dugue died, in July 2014, that her daughter Doris Gadsden-Andrews realized her mother was about to join the millions of Americans who had already lost their homes. That was right about the time that a new batch of opportunists came around, offering to solve the latest problem facing distressed homeowners on Woodbine Street.

Through the window of the house she’d lived in for 25 years, Linda, who Gadsden-Andrews calls the “Woodbine newspaper,” watched the men go knocking on doors all the way down her block. They knocked on 41 Woodbine, and next door on 39, and crossed the street to knock on those doors, too. Linda knew why they were coming. “People were in foreclosure,” she said, her voice rough from years of Newports and spreading news. “Quite naturally, that’s how they got the houses. Once you’re in foreclosure, then they start.”

As the crisis tore through the housing market in 2008, a group of high school friends from Queens decided to get into the real estate business. The men, in their early twenties, founded a company called My Ideal Property, and began to buy near-foreclosed houses in neighborhoods hardest hit by the crisis.

Over the next few years, operating under dozens of company names, the group honed their methods. They sought out people who had been trapped for years in the city’s exceptionally long foreclosure process — homeowners who had often tried, and failed, to get government help. The brokers cold-called and knocked on doors, sweet talking, cajoling, and sometimes strong-arming homeowners into selling their properties. Then the partners gutted, renovated, and resold the houses to affluent newcomers, who were moving ever deeper into Brooklyn’s once low-income neighborhoods as prices rose. According to one former partner’s website, My Ideal Property flipped some 500 homes between 2008 and 2016.

The homes Ryan Serhant is seen selling on Million Dollar Listing made up just a small fraction of this business, but it was a profitable one. BuzzFeed News reviewed property records for 31 of the group’s luxury homes that were publicly listed by Serhant. The group bought the houses from sellers facing foreclosure for a median price of $305,000, and within about 17 months, they had sold 27 of them for a median price of just over $1.5 million.

That kind of deal wasn’t unique to Brooklyn. In the wake of the 2008 crash, as some seven million borrowers lost their homes, a vigorous trade in “distressed” houses spread across the country. Some of the largest players were private equity–backed buyers like Invitation Homes, an arm of the Wall Street giant the Blackstone Group. In the course of a few years, the company bought 50,000 mostly three-bed, two-bath, single-family houses — the kind once built as starter homes. By 2016, it was the largest landlord of single-family homes in the country. In neighborhoods of color with older, more rundown housing, smaller buyers were often the more significant force. They were willing to put in the legwork and deal with more risk.

Borrowers who couldn’t pay found themselves stuck in one of the country’s slowest foreclosure processes.

In 2009, the federal government acted to try to keep more people from losing their homes. It offered financial institutions new incentives to modify or forgive loans. But the solution fell far short. Five years later, an audit of that program found a “staggering” level of misconduct by lenders. The country’s seven largest mortgage servicers “did not give these homeowners a fair shot,” the auditors concluded. The program meant to help up to 4 million Americans yielded just 1.6 million permanent modifications. About a third of those homeowners fell out of the program. Millions more who applied were turned away.

In New York, borrowers who couldn’t pay found themselves stuck in one of the country’s slowest foreclosure processes. Today, some 12,000 foreclosure cases are still crawling their way through court in Brooklyn.“You have petrified average citizens who are sitting on a ticking time bomb,” said Adler Milord, a Brooklyn investor. There, the “emerging Brooklyn developers,” who would usher Ryan Serhant into Bed-Stuy, found their niche.

On a bustling block in the Rego Park neighborhood of Queens, above a pharmacy and a bagel shop, sits the unmarked office of My Ideal Property. The long blocks outside are punctuated with Russian Cyrillic signs. Rego Park and nearby Forest Hills are home to a tight-knit community of Bukharians, first- and second-generation Jewish immigrants from Central Asia who migrated to the area after the Soviet Union collapsed.

The men, who called Serhant in 2015 with a deal, grew up in this diaspora. One of them, Isaac Aronov, graduated from Forest Hills High school in 2004. Public records show he landed a job as a mortgage broker at an office in Rego Park. It was the heyday of the boom. Housing prices were higher than they’d ever been. But the frothy market he entered was already heading toward disaster.

After the crash, Aronov, like Wall Street, was nimble enough to recognize that there was opportunity in distress. In 2008, he started My Ideal Property with some friends from the neighborhood. They were young, ambitious, and willing to work hard. With what one former partner described on his website as “zero experience or financial support,” they began buying homes in some stage of foreclosure.

They gravitated toward the majority black and Latino neighborhoods that were hubs of subprime lending before the crash, and later accounted for over three-quarters of New York City’s foreclosure filings. Taking out short-term, high-interest private loans from wealthy backers in Manhattan and Long Island, they bought fast.

It was a lucrative time to be buying, and investors across the city were busy. A recent analysis by the nonprofit Center for NYC Neighborhoods found that, between 2014 and 2016, more than 5,800 homes were “flipped,” or bought and sold within a year. Half of them were in some stage of foreclosure. Within this rush, the men behind My Ideal Property carved out a significant niche. By 2016, the company had done more than $250 million in deals and employed over 100 people, according one founder's website.

But that aggressive move into troubled neighborhoods has come at a cost for their inhabitants.

A review of court documents by BuzzFeed News found 12 cases where homeowners alleged to have been deceived by the group. One homeowner who the group sued for violating his contract of sale described the contract as “a product of fraud.” Two others claimed that, in the course of a protracted sale process, the group had taken control of the property, changing the locks, and in one case, torn down doors, pulled apart the bathroom, and left it flooded “to obtain a lower property value” from the bank that needed to approve the deals. In four of these cases, the court ruled in favor of the homeowner. In three, the parties elected to discontinue, and in five, litigation is ongoing.

It’s not just homeowners the group has butted heads with. In 2016, Aronov was named one of the city’s worst landlords in an annual list compiled by the New York City Public Advocate. City housing authorities issued 789 violations at the 16 buildings where he is considered the landlord, according to the 2016 list.

Aronov declined multiple requests to speak on the record, but in March, one of his partners, Michael Gendin, spoke to BuzzFeed News at a restaurant in Bed-Stuy. He’s broad-shouldered, with dark hair, casually well put together that day in a white dress shirt and knit vest. He grew up with Aronov, who brought him into the business in 2012. Gendin said he became one of a half-dozen or so partners Aronov worked with over the years as he built a scrappy real estate operation on Queens Boulevard.

By 2015, the investors had a glut of houses in the fast-gentrifying neighborhoods of Bushwick and Bed-Stuy. They were looking for something to help them break away from the pack of other sellers. “We felt like we needed a little magic touch at the top,” said Gendin. “We needed marketing, we needed exposure.” So they reached out to Ryan Serhant. Gendin said it was Serhant who introduced them to Brett Wexler, the lawyer who represented them in the sales of several homes, and who would eventually turn up on Million Dollar Listing.

“I was just a hired gun.”

Serhant told BuzzFeed News he was used to cold-calls from developers, but this was a different breed. "I don't mean Rockrose or Harry Macklowe," he said, name-dropping two of Manhattan's biggest players. These weren't real estate powerhouses, they were just "a group of people that were kind of buying houses and converting them."

They inked the deal in September 2015. At the time, Serhant said it was for about 70 homes. On television, he called it 100. Gendin described it as “roughly 20” and said the big numbers were “for publicity.” BuzzFeed News identified 31 listings. Whatever the case, it was Serhant’s entry into central Brooklyn. “That's really what brought us out there” he told BuzzFeed News. In September 2016, Serhant rolled out a red carpet for his new Bed-Stuy office, in a building Aronov owns.

In response to questions from BuzzFeed News, Serhant said he didn’t know the investors were his landlords, or that the luxury townhouses he was listing had recently been in foreclosure. He’s only there to sell them. “I was just a hired gun,” he said.

Gendin, however, is candid about the fact that “distressed assets” are his business. “There’s no secret to anything,” said Gendin. “Someone is in foreclosure, you call them up — ‘Do you want to make a deal?’ It’s very simple. You buy the asset, you renovate the house, put it on the market. You attach a Ryan Serhant, a big name, and you sell it for top dollar. There’s not much to it at the end of the day.”

These deals were far from simple: Homeowners had to be convinced to sell. Banks had to be convinced to let the properties go at a discount. Houses had to be gutted and rebuilt fast. BuzzFeed News dug into the property records of the 31 homes that Serhant has listed for the developers, as well as nearly 200 others the group acquired in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Sometimes a single acquisition took years. More than a dozen involved lawsuits, which flew in each direction — sometimes investors claimed homeowners were trying to back out of a deal, other times owners would claim the investors had misled them.

Central to their approach were so-called “short sales,” in which a lender lets struggling borrowers sell their home for less than they owe on the mortgage, thereby avoiding foreclosure. After the crash, the Obama Administration pushed short sales as a solution to stem the tide of repossessed homes. It was considered a decent solution. Borrowers walked away empty handed, but avoided formal foreclosure. Banks accepted the highest bid — whatever the market would bear — and settled a bad debt. Buyers got access to homes that might otherwise languish in the foreclosure process for years.

But it wasn’t supposed to be a fire sale. “Short sales are not a way for people to get a bargain,” said Rose Marie Cantanno, the associate director of foreclosure prevention at the New York Legal Assistance Group.

Yet for savvy investors, short sales did become a way to get a discount. Buyers with cash, tenacity, and time were the most inclined to risk buying these houses, which often came “as is” with the risk of violations or squatters, damaged walls, or cracked foundations. This created a kind of insider’s market. In an upcoming report, the nonprofit Center for NYC Neighborhoods found that flippers who bought in central Brooklyn in 2014 and 2015 paid 30% to 40% less than sales of comparable properties in the neighborhood. The report, provided to BuzzFeed News, suggested this was because flippers purchased distressed houses “that non-professional home buyers never competed for,” or may have bought “from homeowners who do not understand the full value of their homes.”

Investors looking for short sales "have like a lotto mentality,” said Jomo Gamal Thomas, a real estate attorney in Brooklyn who has worked on short sales. “They will put in an offer for $150,000 or $200,000.” If the bank rejects the offer, they counter, citing violations, squatters, busted pipes. To get the best price, investors create a perception — sometimes true, sometimes trumped up — that the property is a headache the bank does not want, said Thomas.

When the market in Bushwick and Bed-Stuy exploded, the potential for profit was so clear that everyone got in on the game, Gendin said. “You had the barbers and the jewelers and everybody coming in and trying to do a short sale,” he said. “That’s what started happening, people just stepping on your toes.”

“I'm the only one who didn't know nobody.”

Aronov and his partners found ways to edge competitors out. They built a short sale machine, through which they controlled every step of the process. They combed foreclosure filings, calling owners, leaving letters, and going door to door looking for “people who needed to get out of a situation,” Gendin said. They provided a broker, sometimes an attorney, and handled all the negotiations with the bank.

Often, they offered cash up front, according to interviews with homeowners, an offer some found hard to turn down. In exchange, many signed a deed or a contract promising to sell to the group. While counterintuitive, it is not illegal for someone to transfer their deed without settling their mortgage. That meant Aronov and his team owned the home, giving them leverage with the lender, and locking out any competitors who might try to make a higher offer. Once the lender accepted the offer, the group bought the home through a limited liability corporation, or occasionally sold it to other local investors.

This process could take months or years. Meanwhile, homeowners watched their debt compound. Bound to contracts, some of which had no expiration dates, their only choice was to wait. They could not walk away and find another buyer, even if they got better offers, and even as they watched prices rise all around them during Brooklyn's meteoric property boom.

Homeowners like Travis Harris found the whole process somewhat mystifying. In July 2016, Harris, a city transit worker, said he went to My Ideal Property’s office on Queens Boulevard to close on the sale of his two-family house in Bushwick. It had taken two and a half years for the group to negotiate a short sale on the property he had bought for $637,000 with an adjustable rate, interest-only subprime loan in 2007. When Harris arrived, “I'm the only one who didn't know nobody,” he said. “It was the buyers, the lawyers, the title company — it was like everybody knew each other really close.” That day, the home — which, Harris admits, had a slew of outstanding building violations — sold for $240,000 to an investor who has bought a number of properties Aronov had in contract.

Harris said he thought the price was low, but along with seven other sellers BuzzFeed News spoke with, he didn’t object. They said it seemed like their best option to get out of foreclosure. “I would have loved to have kept the property but I just couldn't do it,” said Harris.

Some other deals did get ugly, with both property owners and investors suing one another. In court filings, owners accused the investors of deception. If owners stopped responding to the group’s calls, or tried to work with someone else, the investors sued, alleging owners had violated their contract and asking the court to grant the investors the house.

Denise Riera never sued, but she did send a complaint to the state attorney general’s office. In 2013, the 57-year-old black probation officer was desperately looking for a way out of foreclosure. She listed her house and got an offer from an investor to buy it in a short sale for $175,000 and give her $10,000 to start fresh — if she signed over a deed before the sale went through. She balked. But then the buyer referred her to a lawyer, Yariv Katz. Riera said she was told he would represent her for free. “He made me feel comfortable,” Riera told BuzzFeed News. “I was so stressed out and so nervous. Maybe I wasn’t listening between the lines.”

In December 2013, Riera signed her home over to PIM Equities. Aronov signed for the company. She said she left with $2,000 and a promise of $8,000 more when the bank greenlit the sale. But the bank rejected the investor’s short-sale offer, saying it wouldn’t accept anything under $395,000.

The deal languished. Then in December 2014, not long after the company had evicted Riera’s family, someone called the Department of Buildings to report that a group of men had pulled up to the house in a white van. They went in “with bats and hammers,” the complainant said, and “there was a lot [of] banging.” When Riera saw her house next, she said she found holes in the walls in the bedrooms and bathroom, the kitchen sink of one apartment had been torn out, and debris was littered throughout the house. (BuzzFeed News found no evidence linking the destruction to Aronov’s group, and Aronov did not respond to questions about Riera’s property).

In May 2015, Riera received an email from Alex Frias, an employee at My Ideal Property, who asked her to sign an affidavit they would then file in court to contest her foreclosure. “The bank has demanded an unreasonable amount to settle the short sale and therefore we need to file these papers to put pressure on them and get them to bring down their demand,” Alex Frias wrote in another email to Riera, whose attorney provided it to BuzzFeed News. “Once we accomplish this we’ll be able to close on the short sale.”

Investors bought for the home for $400,000. They sold it nearly a year later for $1.5 million.

“That’s when I got really suspicious,” she said, and refused to sign the documents. Nearly four years later, Riera is in limbo. Still saddled with the mortgage, she cannot sell the house and settle her debt because her deed now belongs to PIM Equities, which she said has refused to return it. In March, Yariv Katz, the lawyer who encouraged her to sign away her house, was among 11 people indicted for allegedly trying to defraud people out of their homes. Indicted with him was a second attorney, Michael Herskowitz, whose name also appears on Riera’s paperwork. Both appear regularly on records for properties bought by the group, including five of Serhant’s listings. Neither Katz nor Herskowitz responded to several requests for interviews.

At a café on Halsey Street in Bed-Stuy, Gendin acknowledged that the group referred homeowners to Katz, but that the lawyer wasn’t involved in the deal with Riera, and couldn’t comment on it directly. If someone wanted out of a deal, “most of the time we let them out,” he said, as long as they repaid money the investors had shelled out as down payments, or on getting rid of tenants through evictions or buyouts.

Down the block from the café was 414 Halsey Street, one of the houses Serhant toured on this season’s Million Dollar Listing premier. Gendin signed the deed for the home, which investors bought for $400,000. They sold it nearly a year later for $1.5 million.

Those kinds of purchase prices were comparable to other sales of rundown houses in the neighborhood, Gendin said, adding that if they weren’t fair, the lender wouldn’t have agreed to the sale. “That’s what the bank was willing to let it go for,” he said. He also said that between the $400,000 purchase price and the $1.5 million sale price were extensive costs paid for by the investors.

“Tenants. Evictions. Estates. Attorneys. Other liens. Water. Taxes. Violations. Filing the job. Getting permits. Construction. GCs [general contractors]. Selling the house. Brokers on the way out. Closing costs,” he said. “That’s the thing. Everyone just sees the number from one to five. They don’t see everything in between.”

“People think we take advantage of people,” he said. But those complaints, like the lawsuits against them, can’t be taken at face value because the critics are usually “an attorney who’s trying to make a profit, a competitor who’s trying to make a profit, a squatter,” he said.

“In terms of swindling people out of their homes, or taking their homes, I’ve never really had that issue,” he said.

“I can’t answer the question, ‘Are people happy now that they sold their house?’ because of the trend and the prices that went up," he said. "But back then, yes, because they were taken out of a situation.”

To Gendin, the people he did deals with did not “lose” their homes. They, like the investors who knocked on their door, looked at the landscape, and made a calculated decision. “Everyone has free will,” Gendin added. “Everyone has choices. So the heirs of — what is it, Woodbine? — had a choice to make. They didn’t have to sell. They didn’t have to agree to $10,000, or $100,000, or whatever it was.”

One day not long after her mother died, Gadsden-Andrews sat in her little office at 41 Woodbine St., trying to figure out a way to save her family’s houses. Most of the time, Gadsden-Andrews' high energy and exuberant styles made it hard to believe she was in her late 50s. But sorting through her mother’s affairs that summer, she felt the stress wearing her down.

Gadsden-Andrews wanted desperately to save the houses. They represented decades of her mother’s struggle to leave an inheritance for her family and to provide shelter to the mentally ill people who had lived there for years. “We wanted to keep her legacy, if you will, alive,” Gadsden-Andrews said.

But she felt poorly equipped to figure out how. Though Gadsden-Andrews spent years helping her mother run her storefront church and taking care of the House of Hope’s residents, Dugue, a fiercely proud woman, had hidden her financial trouble from her daughter. The numbers Gadsden-Andrews saw on the bills that her mother left behind felt enormous. They stated Dugue owed nearly $671,000 on 38A and $542,000 on 41. Gadsden-Andrews called the banks, looking for someone to help her understand the figures.

"We did not know anything. We were ignorant to every aspect of real estate that there is."

Gadsden-Andrews didn’t know the first thing about real estate, much less negotiating her way out of a foreclosure. Her sister, living back in South Carolina, didn’t have much advice. Her two other siblings, still living at 41 Woodbine, were both ill and sinking deeper into addictions they’d struggled with for years. She and her husband, Robert, lived in public housing, but they thought perhaps he could take out a veteran’s loan to try to save number 41. “When the blind is trying to lead the blind you ain't getting very far,” said Robert Andrews.

One day that fall, a car pulled up to 41 Woodbine St. A couple of young men got out and approached her. They knew she was in foreclosure, she said, and they offered to help. “The first thing is they say ‘we can help you get out of debt,’ not, ‘we can take your house from you,’” said Gadsden-Andrews. “So that's where they got us, because we did not know anything. We were ignorant to every aspect of real estate that there is.”

Not long after that first knock on the door, Gadsden-Andrews said the men told her the houses were unsalvageable, but they could buy them, settle the debt, and give them some money to walk away with. Gadsden-Andrews paused. She wanted to see if there were better offers out there. “The neighborhood was up and coming so I knew that they would be worth something,” she said.

But while she hesitated, My Ideal Property approached Dugue’s husband, Victor, who did not respond to calls from BuzzFeed News seeking an interview. Gladis Dugue died without a will, entitling Victor to half her assets. Over the next few months, he signed a series of deeds transferring his share to an Aronov-linked company, Hancock Management, LLC.

In January 2015, a pair of manila envelopes arrived in the mail for each of Dugue’s children. They opened the documents to find Hancock Management, now a half-owner, was suing them to force the houses’ sale. It’s a tactic advocates said they’ve seen investors use more as the stock of cheap homes dwindles. “They will even buy a piece of a home, because they know once they have a foot in the door, they're in,” said Jennifer Sinton, director of the Foreclosure Prevention Project at Brooklyn Legal Services.

The threat of the lawsuit worked. “The wear and tear, they were wearing me down,” said Gadsden-Andrews. “And I did, I caved.”

At My Ideal Property's Queens office that February, Gadsden-Andrews signed a stack of documents. Among them were deeds to the houses. As her mother’s legacy slid away, she was adamant that she be given time to figure out where the mentally ill and addicted residents of the House of Hope could go. It took her eight months. Each move was difficult. “You see the people that your mom cared for all these years crying and don’t want to leave,” she said. “It was very sad and very hurtful.”

Her siblings also had to find some place new. Her sister, Tony White, eventually found a subsidized apartment in Manhattan. Her eldest brother, Ray White, went to a nursing home. He died of cancer in December 2015, just before the short sale on 41 Woodbine St. went through.

Property records show that house sold for $265,000, and 38A for $440,000. Aronov signed as the buyer for one. A Tomer Aronov signed for a second. Documents from Gadsden-Andrews show the siblings split $50,000 in “relocation” fees paid to them by one of Aronov’s companies. Gadsden-Andrews said she believed her mother’s widower received money as well. Less than eight months later, Ryan Serhant’s team resold the houses, each for over $1.2 million.

Last winter, in the picture-lined living room of their housing-project apartment, Gadsden-Andrews and her husband, Robert, said though they felt their hand was forced, they signed the documents knowing that it meant losing the houses. It’s not that they felt like the investors who came to them broke the law, they said. It’s more that everywhere the family turned, the law seemed to be working in someone else’s favor.

“We have laws in place for all kinds of stuff,” said Robert Andrews. “There isn’t something in place law-wise to protect individuals who are subjected to this.”

Although there is no evidence that My Ideal Property broke any laws, both lawmakers and law enforcement have made efforts to protect homeowners who are underwater. On an industrial block in Queens, investigators for Sheriff Joseph Fucito’s office chart constellations of limited liability companies that radiate out from addresses like spokes on a wheel. They often suspect these elaborate networks are doing something predatory. But investigations are time consuming and complicated, particularly if a homeowner took money or signed documents. “They don't make good stories or prosecutions,” said Deputy Sheriff Maureen Kokeas.

Prosecution is not the only, and perhaps not the most effective, tool to protect homeowners. Lawmakers in Albany have proposed legislation that would tax quick-turnaround sales and increase transparency of limited liability corporations. Meanwhile, the state attorney general’s office has been trying to reach New Yorkers facing foreclosure. They’ve identified neighborhoods where owners are most vulnerable. They pin fliers in bodegas and go door to door trying to connect them with people who can help.

But the competition has a head start. Speculators have moved on from Bushwick and Bed-Stuy to case neighborhoods farther out, where, bucking trends elsewhere in the country, foreclosures are on the rise. Property records show My Ideal Property has made purchases deeper into Brooklyn, up in the Bronx, and in Jamaica, Queens. There, placards offering cash for houses are stapled to telephone poles, foreclosure relief attorneys hawk their services on billboards, and cardboard signs read “REAL ESTATE INVESTOR SEEKS APPRENTICE EARN 20K PER MONTH.” A hub of black homeownership, Jamaica was badly hit during the crisis. Today it has among the highest rates of flipping in the country.

In New York, buying a home is accessible to a narrowing slice of people at the top. “To buy something that’s livable for less than $1 million is very hard,” said Douglas Bowen, a broker at Douglas Elliman. “It’s nearly impossible in Bed Stuy now.”

On a warm September night a year after Ryan Serhant announced the deal with Gendin and Aronov, he celebrated the opening of his new Bed-Stuy office. Dressed in a slim-cut gray suit, Serhant stood on the red carpet that had been rolled out on the sidewalk for the occasion. A photographer snapped a couple of photos of Serhant with his Brooklyn team, which he boasted had that year done $312 million in sales. Then he broke away to welcome a group of newly arrived guests. One asked how business was going. “We sell a house out here, like, every other day,” he said, ushering them into the back garden for cocktails and portobello-cap hors d'oeuvres. “It’s, like, the greatest market ever.”

For Serhant, the housing crash was a kind of necessary rest. “The market is like anything else, it needs naps,” he said during an interview in March. “It's like people. It needs to sometimes take a little break.” The subsequent boom is, to him, proof that “everything will be okay if you have faith in the system and faith in the market,” he said.

Serhant’s own career seems to confirm that faith. Now 32 years old, GQ handsome, a TV star, and a millionaire, Serhant has little patience what he calls the “grouchy” critics of soaring prices in New York’s lower and middle class strongholds. To him, surging home values signal progress. “I think progress is a good thing,” he said. “If you don't like it then there are open swaths of land in South Dakota that will be the same for the next hundred years. I can almost guarantee it. So they should go there.”

When Evan Padget and his wife first toured 41 Woodbine St. in May 2016, they hesitated. They understood the optics of a young, affluent white couple moving into a fast-gentrifying neighborhood of lower-income black and Latino families. “When we thought about buying it was just like, Do we want to be part of this?” he said. “At the same time, we wanted to live in New York.” If they didn’t buy soon, they worried they might be priced out. “We were excited to buy a new house,” said Padget. “It should have been a good thing.”

But then came Dugue's collections letters, the family members at the door, the boxes of bible literature. Padget, curious about the history of his new house, pulled the property records.

The investors who sold him the house paid $265,000 for it, just six months before he bought it for $1.3 million. A search along the block turned up a pattern — 38A was bought for $440,000, 39 for $310,000. He Googled Aronov and found him on the city’s “worst landlord list” thanks to scores of building violations on properties he owned. He searched his own home, and saw that Gendin and Aronov had been hit with serious violations in the whirlwind construction. Then there were the lawsuits against the investors he had bought the house from, in which homeowners alleged they were forced to leave or to sign things they didn’t understand.

“What we deduced was that it was people were in, you know, like really tough financial situations,” Padget said. “They're just making financial decisions that obviously are not in the best interest for them, and they just feel cornered into it.”

Padget loves his neighborhood and looked forward to building a life there. But he said he didn’t fully grasp, until 41 Woodbine became his, the complicated story of race, class, and home that he bought into. “It felt like it wasn’t right,” he said. “We were unwittingly part of this.”

Tony White, Dugue’s youngest child, lived on Woodbine Street until the summer of 2015, less than a year before Padget took his first tour through house where she was raised. “No matter where I went in my life, how far I got, I always knew I had 41 Woodbine,” she said. “It was a home. It loved us, we loved it. The house was like family, you know.”

Like the neighborhood she grew up in, Tony’s life has undergone a radical shift. She dug herself out of drug addiction, found an apartment through a subsidized housing program, and transitioned from male to female. In an East Village diner not far from where she now lives, White described the loss of the houses on Woodbine Street that her mother had held onto all those years. “I wouldn't want this to happen to nobody,” said White. “Something like this is devastating.”

She paused, trying to explain it better. Then she tipped her head to the left and pulled back her hair. On her neck, XLI, 41 in roman numerals, was inked into her skin. Her sister, Doris Gadsden-Andrews, has an identical one. So do Gadsden-Andrews’ children, and her sister, and her sister’s children. They left their home, but not their history, she said.

“All of us have the number 41 tattooed on us because that’s where it all started,” said Gadsden-Andrews. “It was for remembrance, so we don’t forget what my mother did.” ●

This article was written with the support of an investigative reporting grant by the Urban Reporting Program of the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism.

Lisa Riordan Seville is an independent reporter based in Brooklyn, New York. Her work has appeared on NBC News shows, NBCNews.com, The Guardian, The Nation and Vice, among other outlets.

Lukas Vrbka is an independent reporter and researcher based in Brooklyn.