In the fall of 1998, Mozhan Marnò, then a Barnard College sophomore, entered her 48-year-old photography professor’s office for a final one-on-one critique for the semester. The professor, Thomas Roma, told her he had been thinking about her a lot lately. She asked him what about, and he responded that he couldn’t say.

“People get in trouble for those kinds of things,” he said, according to a sexual harassment complaint Marnò — then known as Mozhan Navabi — would later file with Columbia University.

“What kind of trouble?” she asked.

“People lose their jobs.”

By the time she left his office that day, Roma would tell her that he didn’t have to see a seminude self-portrait she submitted for class again because “he knew exactly what it looked like.” The next semester, Roma would pursue Marnò aggressively, at one point inviting her to his office, where he would kiss her, undress her, and put her hand on his penis. Their affair was consensual, Marnò said, but manipulative and an abuse of his power. She eventually reported him to the university.

After that, Roma would continue to work at Columbia for two more decades.

At the time, Columbia’s policy — like that of many schools — did not prohibit the 48-year-old Roma from propositioning his 18-year-old student. In fact, the university did not restrict professor-student relationships at all until 2012. With such relationships permissible by default, it was up to Columbia to decide only after the fact, and only after a student filed a complaint, whether a relationship was predatory — to, in other words, be reactive to misconduct rather try to prevent it before it happened.

In Marnò’s case, a Columbia panel determined that she had “provoked and contributed to” her professor’s actions, and offered to “expunge” Roma’s records if the university was not made aware of any similar complaints within two years. At that point, the school already knew of at least three complaints, interviews and documents obtained by BuzzFeed News show.

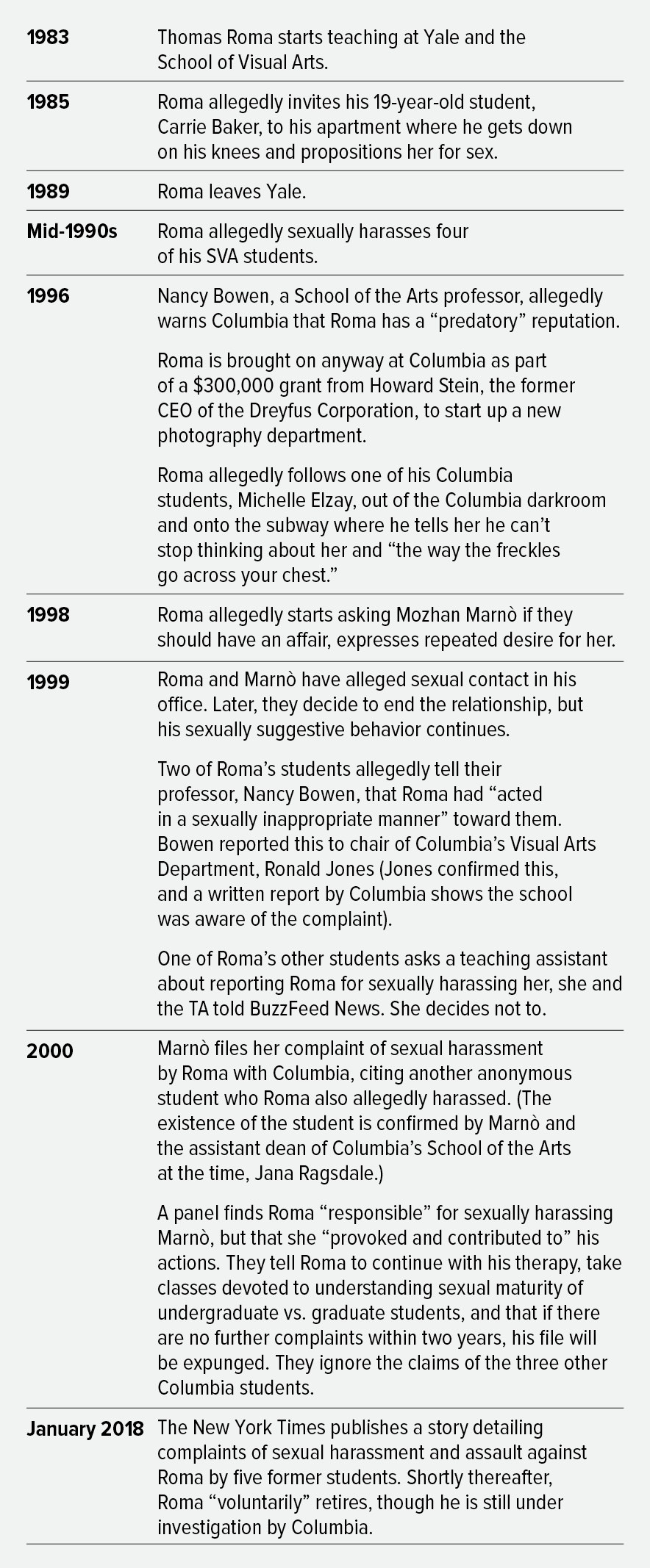

In January, Roma “voluntarily” retired after the New York Times revealed a pattern of sexual misconduct with Marnò and four other students. BuzzFeed News obtained Marnò’s original sexual harassment complaint, as well as dozens of documents detailing the school’s internal analysis, investigations, and policies concerning sexual harassment and gender-based discrimination, and interviewed more than 40 Columbia students, faculty, and administrators about their experiences from the 1990s to the present. These documents and interviews indicate that Columbia leadership knew that Roma, a powerful and well-connected professor who brought funding into Columbia, had a pattern of having inappropriate relationships with students, but kept him employed at the university for decades. They also pose critical questions about what universities should do now about past misconduct, and the power dynamics inherent in professor-student relationships — even consensual ones.

“In academic settings, young women can feel as if they have equal power with their professors, but it’s an illusion,” Ann Olivarius, whose law firm, McAllister Olivarius, is among the most well-known firms to handle sexual misconduct cases against U.S. universities, told BuzzFeed News. “The whole circumstance means they are in an inferior position, and while they may feel their consent is uncoerced, the professor retains power over them that provides the fundamental basis of his possible sexual access.”

In a BuzzFeed News survey of 25 universities around the country, 17 had no explicit ban on professors having a romantic relationship with undergraduates of the school who are not in their classes. At Columbia, professors are not prohibited from having relationships with students that they do not “exercise academic or professional authority” over. (In February, after Roma’s retirement and detailed inquiries from BuzzFeed News pertaining to the university's policy, Columbia President Lee Bollinger told the Columbia Spectator he intended to ban all professor-undergraduate relationships.)

"In academic settings, young women can feel as if they have equal power with their professors, but it’s an illusion."

“These policies vary among universities, but experience shows almost none is strong enough to protect students,” said Olivarius.

“It’s the students, usually women, who pay the price,” Olivarius continued. “We think the right approach for universities is to ban faculty relationships with undergraduates and with graduate students in the same department, which right now is rare.”

As more and more women are speaking out about past experiences of sexual misconduct, these schools are left to grapple with how to treat professors like Roma: powerful, respected figures who engaged in behavior that was not necessarily uncommon or against the rules at the time, but might now fall under the umbrella of sexual misconduct by today’s standards. Often the most powerful professors in a university are ones who have been at the school throughout many years and many policy changes. If allegations arise, should a school punish them based on the standards of when the incidents occurred, or the standards of today? Columbia, for one, hasn’t yet figured it out.

“Allegations of misconduct in the past [are] obviously very complicated,” Bollinger told the student newspaper. “They may not have violated policies. How do you deal with change of mores? How serious was it? What are the possible consequences of this fact being known now? Is somebody a threat to current students because [of] what you now know? There’s no simple answer.”

Roma did not respond to multiple phone calls and emails from BuzzFeed News, nor to a list of detailed questions sent to him and his lawyer. His lawyer, Douglas Jacobs, told the New York Times that the allegations against him were false and defamatory.

In a statement, Columbia University spokesperson Scott Schell told BuzzFeed News that “Columbia treats sexual harassment of students by faculty with the utmost seriousness, as reflected by the fact that Thomas Roma is no longer employed by Columbia, nor will he be permitted on our campus again or allowed to attend off campus Columbia events. Our first and highest priority is the safety and security of our students.”

“We certainly recognize the magnitude of past events reported here and their continued impact for all involved,” Schell’s statement continued. “But they are not reflective of ... current leadership, culture, policies, personnel or approach.”

Roma — who has presented work at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, and who married into the influential family of famous photographer Lee Friedlander — came to Columbia in 1996 as part of a $300,000 grant from Howard Stein, the former CEO of the Dreyfus Corporation, to head a new photography department at Columbia. The chair of Columbia’s visual arts department at the time, Allan Hacklin, told BuzzFeed News that Columbia did not have a photography department before Roma, and that the grant to start the department was “conditional” on Roma being hired as the professor to lead it.

Roma was a star, and Marnò was flattered by his attention when he asked her, in that 1998 meeting, if the two of them should have an affair.

Throughout the following spring, Roma repeatedly made comments about how attracted he was to her and how the semester was “going to be weird” because of their relationship.

“I knew they would say, ‘She’s over 18, so what’s the big deal?’”

Eventually, Marnò said, Roma suggested that they have “a little bit of contact” in his office — with the door closed. According to her complaint, they kissed and he undressed her, with her consent. Out of embarrassment, she didn’t tell Columbia that he also unzipped his pants and put her hand on his penis.

Afterward, Roma told her it would be a good idea if they didn’t have sexual contact again — “until possibly when he was no longer my teacher,” Marnò said in her complaint. She was relieved — but Roma continued to insinuate his desire for her. At one point, she said, he told her she had to leave his office immediately because she was wearing a “such a great sweater.”

According to her complaint, Marnò came to feel manipulated by the powerful professor. Roma “not only initiated this relationship, but he led and controlled it from beginning to end,” she wrote.

She started to question her abilities as a photographer: “I began having more and more difficulty discerning whether the critiques reflected how he felt about me personally,” she wrote, “or the quality of the work itself.”

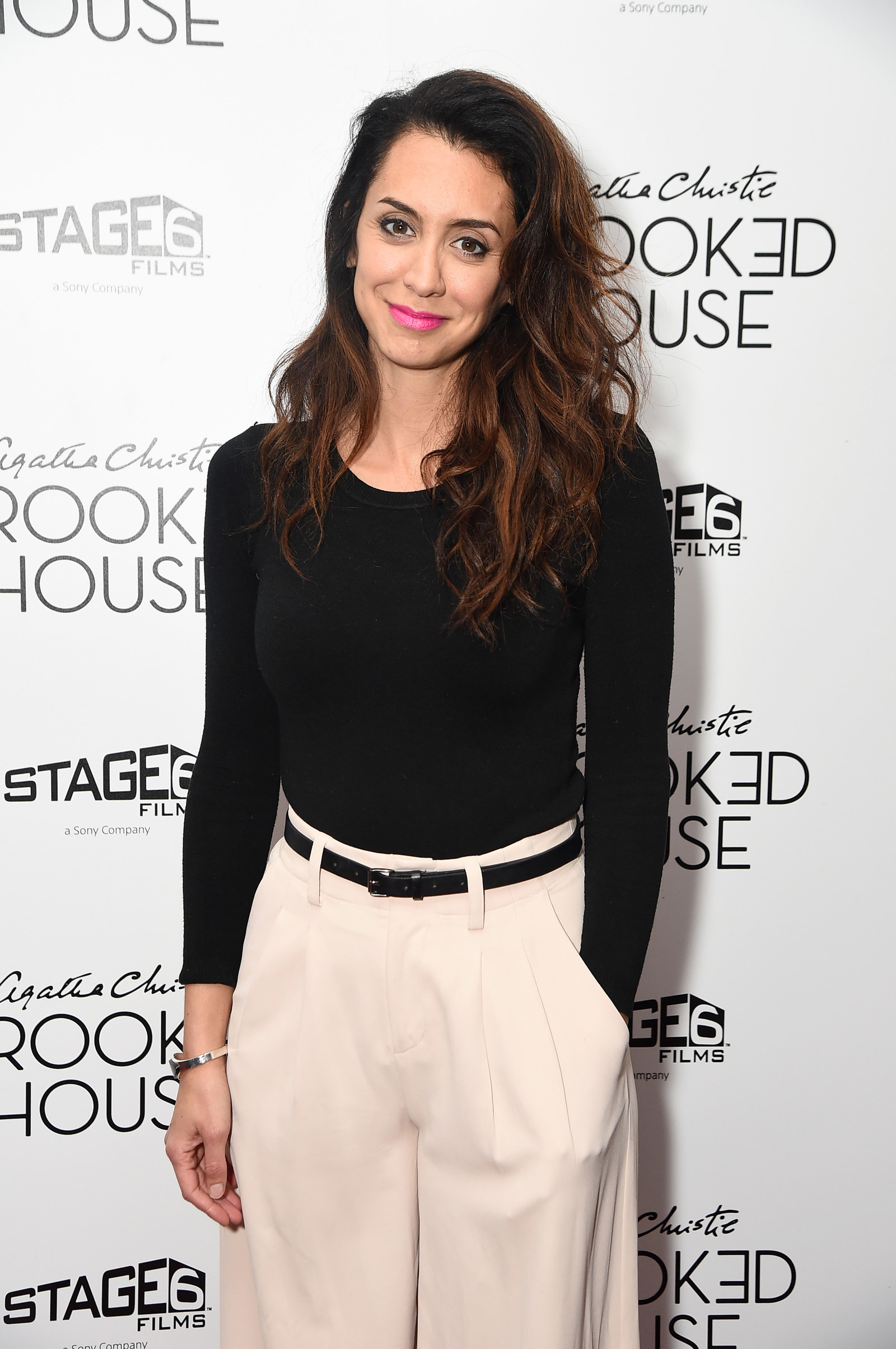

Reached for comment by BuzzFeed News, Marnò, who is now a professional actor, told BuzzFeed News that she “was infatuated with him, but that experience freaked me out.”

“I was really fragile about it, I was embarrassed. I felt stupid, I felt icky,” she said. For the rest of her time at Columbia, she avoided Roma, but was hesitant to report the incident, worried about the Columbia community’s official and unofficial reactions.

“I knew they would say, ‘She’s over 18, so what’s the big deal?’” she told BuzzFeed News. But after another student told her she’d had a similar relationship with Roma, she decided that reporting the behavior was worth the risk. (The student remained anonymous in the written complaint, and BuzzFeed News was unable to reach her. But both Marnò and the assistant dean of Columbia’s School of Arts at the time, Jana Fay Ragsdale, said they remember speaking with her.)

So in her senior year, in 2000, Marnò filed a sexual harassment complaint against Roma.

"I came to the realization," she wrote, "that I should never have been put in the place to have had experienced any of those things, and thus, it should not have been allowed to happen."

According to copies of Marnò’s complaint, the university hearing panel’s response, and a 1999 faculty affairs committee report obtained by BuzzFeed News, at the time of Marnò’s complaint, Columbia had been made aware of two other students who said Roma had “acted in a sexually inappropriate manner” toward them, as well as another anonymous student Marnò included in her complaint.

In his response to Marnò’s complaint, Roma acknowledged that he and his student had kissed, but denied many of Marnò’s other allegations and said he “does not believe her educational pursuits have suffered.”

In the end, a panel of faculty members found Roma responsible for sexually harassing Marnò. But they also determined that Marnò “provoked and contributed to” Roma’s actions. Roma was told to continue going to a therapist, and to attend “workshops or courses” specific to “increas[ing] his understanding of the developmental issues extant with late adolescent/early adult undergraduate students, especially with regard to their sexual and cognitive identities, as opposed to the greater expected maturity of graduate students.”

Marnò’s complaint would be kept in a confidential file for two years, the length of Columbia’s photography program. After that, if no “similar incidents” were reported to the school, the file should be expunged, the panel wrote.

Meanwhile, Columbia told Marnò that if she wanted to keep taking photography, she could take classes at another university. The school would make an exception to its usual policy for her, it said, and allow her to transfer the credits. Columbia did not acknowledge the second student mentioned in Marnò’s complaint.

“I don't think I placed much faith in the educational system after that,” Marnò told BuzzFeed News, two decades later. “I didn't forge personal relationships with teachers. I didn't invest in the place as a whole.” From then on, Marnò viewed having mentor relationships with men impossible.

In response to questions from BuzzFeed News, Columbia would not say whether it did, in fact, expunge Roma’s record as the panel recommended. Columbia added that under current practice, the university does not expunge records, and that it had not done so in the memory of administrators working on sexual harassment cases today.

Ragsdale, the former assistant dean at Columbia’s School of the Arts who helped Marnò file a complaint, told BuzzFeed News last month that she felt “defeated and disillusioned” by the way Columbia handled Marnò’s complaint. “It felt as though I had failed Mozhan and the other student,” Ragsdale said. “I was disappointed and disturbed enough that at the beginning of the #MeToo movement, Mozhan was the first person that came to my mind, over 17 years later.”

In interviews with BuzzFeed News, four women in addition to those who spoke to the Times said they were sexually harassed by Roma: two at Columbia, one at Yale University, where he served as a lecturer from 1983 to 1989, and one at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, where he was a professor from 1983 until coming to Columbia in 1996.

Many of the students’ experiences follow a similar pattern: Roma gave them special attention in class and made repeated comments about their physical appearance. He told them that he “couldn’t stop thinking” about them, and then sexually propositioned them.

Professor-student relationships were not expressly forbidden at Yale and Columbia when Roma taught there. In all cases but Marnò’s, the student did not make a complaint, often out of a fear about how universities would handle it.

In 1985, Roma invited Carrie Baker, then a 19-year-old undergraduate at Yale, to his apartment under the pretext of meeting up before joining others for drinks. There, he got down on his knees, Baker said, and propositioned her for sex, which she refused. In an interview, she told BuzzFeed News she found his behavior “coercive” and “abusive.”

A former SVA student told BuzzFeed News that in 1995, Roma professed his love to her one day after class. The student — who is now a working photographer and requested anonymity for fear of professional retribution — said she was “flattered” because she wanted “a mentor relationship” with him. The two started meeting for coffee dates, where Roma would discuss the logistics of them having an affair and “creepily rub my arm and caress my neck and stuff,” she said. He would sometimes interrupt class to tell her to meet him in the hall, where he would ask her to kiss him. Eventually, she discovered he’d been behaving similarly with many other students, and felt manipulated and repulsed, she said.

“I was crushed,” she told BuzzFeed News, “because this guy I had on a pedestal turned out to be no better — in fact far worse — than all the other men in my life.” After she made it clear that she was not going to sleep with him, she said, he started “getting really nasty to me in class.”

SVA did not return multiple requests for comment from BuzzFeed News on its policy on professor-student relationships when Roma was a professor in the '90s, but the school’s current policy states that exceptions may be granted in “extraordinary circumstances.” Three more of Roma’s SVA students — Allison Ward, Angela Cappetta, and Ilana Rein — recalled having negative sexual encounters with Roma to the Times. Ward described the encounters as consensual but “predatory.” Cappetta and Rein described Roma placing their hands on his crotch. Cappetta also described him asking repeatedly to take her portrait in her home, touching her breast, and asking her to have sex with him, which she declined. A spokesperson for SVA told BuzzFeed News that it does not have a record of any complaints against Roma when he taught there.

Yale would not say whether it had record of complaints against Roma. Sarah Stevens-Morling, a spokesperson for Yale’s School of Art, said the school does not comment on the nature of any specific complaint, and pointed BuzzFeed News to a statement by its dean, saying, “sexual harassment will not be tolerated either within the School of Art, or in formally associated communities aimed to advise, counsel, or to support the School.” Yale prohibited sexual relationships between professors and students who they oversee by 1998, then prohibited all consensual relationships between professors and undergraduate students in 2010.

In addition to Marnò, two other students told BuzzFeed News Roma harassed them during his time at Columbia. New York-based artist Michelle Elzay told BuzzFeed News that in 1996, Roma’s first year at the school, he made repeated sexual innuendos about her in class and that he would frequently share details about his sex life so graphic that she remembers them acutely two decades later.

One day, said Elzay, who was a 21-year-old MFA student at the time, Roma followed her out of the darkroom at Columbia and onto the subway, where he told her he couldn’t stop thinking about her and “the way the freckles go across your chest,” she said.

Three years later, in 1999, Roma’s behavior caused an undergraduate student to run out of his office and immediately drop the independent study she was doing with him, she told BuzzFeed News. The student also said Roma described a sexual dream to the entire class, all the while staring at her so directly that she was later asked about it by other students. (She asked a teaching assistant about reporting him to the administration but in the end decided not to. The teaching assistant confirmed to BuzzFeed News that the undergraduate did, in fact, make this request.)

A third woman, Ash Thayer, who was Roma’s student as an undergrad at SVA and became his teaching assistant while getting her MFA at Columbia, told the Times that in 1999, she was working at his desk when Roma told her that a mutual friend of theirs had died. Thayer was in shock. Roma then asked her to turn around, according to her account in the Times. When she did, he had his penis outside of his pants, erect. He moved toward her and she said “no” repeatedly before he put his penis in her mouth, she said. At first, she froze, then she pushed him away and left the room.

Nancy Bowen, a former School of the Arts professor, told BuzzFeed News that she was aware of Roma’s “predatory” reputation and tried to warn Columbia about it before he was hired. But the university hired him anyway.

In the spring of 1999, two female undergraduate students approached Bowen and told her that Roma had “acted in a sexually inappropriate manner” toward them. She said she informed Ronald Jones, the chair of Columbia’s visual arts department from 1998 to 2000, who confirmed to BuzzFeed News that Bowen came to him with the allegation. “In every instance where inappropriate behavior was reported directly to me I, in turn, reported it upwardly,” he said. (BuzzFeed News obtained a letter of grievance showing Bowen reported the complaints of these students, and a report written by Columbia in response confirms that the school was aware of this complaint and that Bowen “had opposed his appointment.” Columbia did not comment.)

Professor-on-student harassment is a national problem. Professors from the University of California, Berkeley; the University of Washington; Caltech; and Yale, among others, have faced accusations of sexual harassment by their students — with their alleged sexual misconduct sometimes going back years.

At Columbia, two other professors faced consequences from the school after being accused of harassment by former students. The university reportedly found Thomas Pogge, the renowned ethicist, responsible for sexual harassment allegations when he was a professor at the university in the 1990s. As in Roma’s case, Columbia told Pogge he was no longer allowed in the same room as the student he harassed, but kept him employed, colleagues from the time said in an affidavit. (Pogge is still employed as a professor of philosophy and political science at Yale, which reportedly hired him despite of knowing about the allegations made against him at Columbia.) In December, classics professor William Harris retired as part of a settlement of a lawsuit in which Columbia was accused of improperly handling sexual harassment complaints. Following the suit, more students from Harris’s three decades at Columbia came forward about him behaving inappropriately with them.

BuzzFeed News obtained documented evidence of three more sexual harassment complaints filed by Columbia students against their professors, including one against a department dean. Two of the complaints were filed around the same time as Marnò’s, and one was filed in the past few years. BuzzFeed News was unable to obtain Columbia’s full decisions but was able to reach two of the three original complainants, and confirm that all three professors are still employed by the university and have been for more than two decades.

Columbia acknowledged societal norms around sexual harassment are rapidly changing. “We recognize that college and university campuses do not exist apart from the widespread re-examination of workplace conduct that has dominated so much of the nation’s attention in recent months," the university told its students and faculty in a December email announcing Dr. Harris’s departure, provided to BuzzFeed News.

Columbia’s current policy, last updated in 2015, says that should a professor and one of their students enter into a sexual relationship, one or both of them should alert a member of the administration, so that it can be arranged for the student to no longer be under that professor’s authority and to prevent possible harm to the student, professor, and university. A spokesperson for Columbia went further, stating that professors should disclose a potential relationship with a student before it even begins.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, many universities, including Columbia, had policies “discouraging,” but not outright forbidding, professors from having sexual relationships with their students. In 1997 when the courts found that universities could be financially liable for sexual harassment, this began to change, but it wasn’t until the 2010s — when Obama administration promised that it would investigate the handling of sexual assault accusations at dozens of colleges — that banning relationships between professors and the students they oversee became more common. Since then, only a handful of schools have gone further than this, banning all relationships between professors and undergraduates.

Of the 25 colleges surveyed by BuzzFeed News (7 New York state universities, 10 public universities considered academically comparable to Columbia, and all 8 Ivy League universities), 17 do not fully ban relationships between professors and undergraduate students not under their supervision, while 8 have a total ban on relationships between professors and undergraduate students. Meanwhile, 5 had no explicit bans on relationships between professors and their students, though all of those “advised against” or “strongly discouraged” them, and put procedures in place for alerting administrators. The most common policy among the schools is akin to Columbia’s: Professors are prohibited from having relationships with students they oversee, but not prohibited from having relationships with other students — graduate or undergraduate — whom they do not hold direct academic authority over.

“It’s like this happened in the 1950s. It was 2000. Everyone knew it was wrong.”

A former senior administrator at Columbia who worked closely reforming the sexual misconduct and discrimination policies in the ‘90s and early ‘00s (and wished to remain anonymous for fear of retribution) told BuzzFeed News that the university has struggled with balancing protection of faculty reputation with “ensuring equity across the whole university.”

“The faculty are why they’re in business — you are expected to protect the people who are helping you maintain your reputation,” the former administrator said about Columbia.

Over the past two decades, Columbia got rid of the statute of limitations for reporting misconduct (enabling reports of incidents like Marnò's to be reinvestigated), increased reporting resources and access, and required faculty to take frequent gender-based misconduct trainings, among other improvements.

“We have long had resources in place, but we have substantially more in the past several years,” Suzanne Goldberg, a Columbia spokesperson, told BuzzFeed News. What happened in the case of Marnò’s complaint would not happen today, she said: Complaints brought today would be reviewed in accordance with the university’s current standards, and would be expected to result in different outcomes.

Ragsdale, the Columbia administrator who helped Marnò with her complaint, said she was “angered” by Columbia’s response to the allegations against Roma. Goldberg, the Columbia spokesperson, told the New York Times that the university “looks differently at these matters today than 20 years ago” when Marnò filed her complaint.

“It’s like this happened in the 1950s. It was 2000,” Ragsdale told BuzzFeed News. “Everyone knew it was wrong.” ●

CORRECTION

Angela Cappetta told the New York Times that the alleged incident involving Roma occurred in her home. A previous version of this article stated that it occurred in his home.