The unofficial merchandise sellers of the Donald J. Trump campaign are a savvy band of roving capitalists. They’re well-traveled (at times logging thousands of miles a week), shrewd in business, often unattached romantically. They deal with all kinds of people. Many have been on the road for months, trailing the campaign trail from rally to rally, selling knock-off hats, buttons, and flags to the Trump faithful.

Since the early days of the primaries, business has boomed for the fringe caravan — one seller paid his tuition and bought a new car on the Donald's tailored coattails. Others say they sell thousands of dollars' worth of gear on good days, in cities like Naples, Florida.

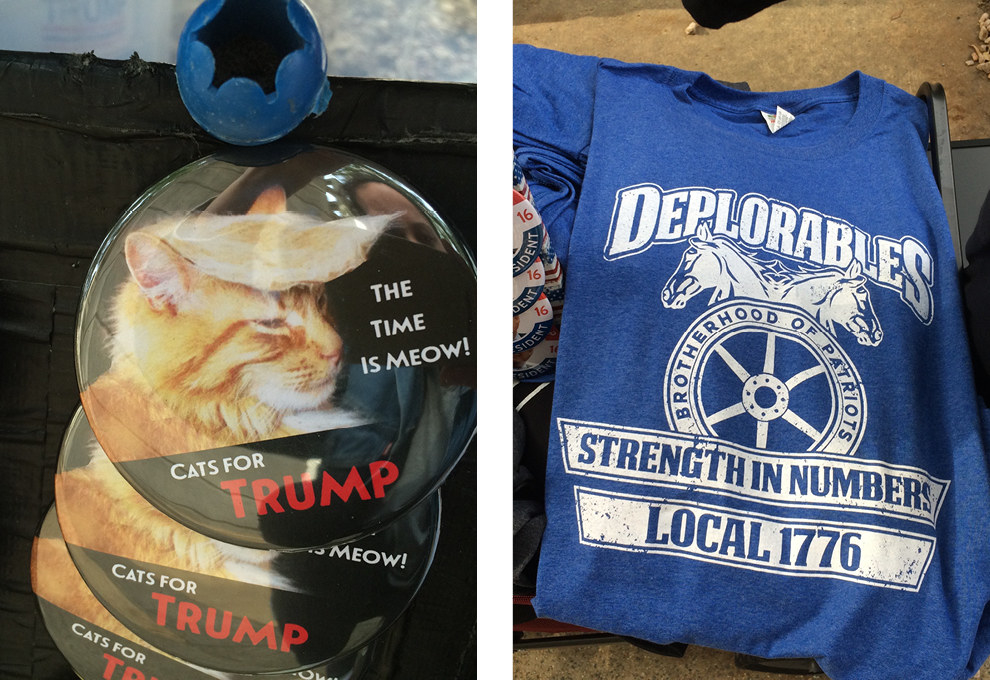

Some are true believers, who parlayed their passion for the candidate into a profitable side gig. Others are professedly apolitical, their only allegiance to a solvent crowd — they’d just as soon be selling pennants outside a ballgame. The sellers treat the candidate as a brand, like they would a beer, a car, or a sports team. Often, they’re among the only people of color in the overwhelmingly white crowds that many Trump rallies draw.

But as Election Day approaches, they’re preparing for the end of the tour. As the traveling Trump carnival enters its final days, the merchants are loading their tents back into their pickups and drawing up plans for what comes next. They don’t expect to see an election cycle as bankable as this one again soon.

As BuzzFeed News covered the Trump campaign this year, our reporters spoke with the vendors at rallies across the country. These are some of their stories.

As campaign season began in earnest, Garrett O’Daniel of Springfield, Missouri, responded to an ad on Craigslist looking for free agents to sell goods for a remote distributor. “Cash paid! Fun!” notices read. “Average earnings per event $250-$600++ for each salesperson.” “Earn $1000-$2000++ per week until election day.”

The then-20-year-old O’Daniel met the qualifications, landed the gig, and recruited two college friends to come along. The trio began by hawking Ted Cruz tees and Bernie Sanders pins, but soon focused on the most lucrative market of the 2016 cycle: anything and everything Trump.

By October, O’Daniel told BuzzFeed News, he’d earned enough to pay for his college tuition. He’d taken a semester off school to sell, which turned into a full year off. He’s invested in a new car and bought a dog.

The troupe's best-selling item, without fail, is the Donald’s “Make America Great Again” cap, O’Daniel said. Trump's presidential campaign has spent more money on hats ($3.2 million) than polling ($1.8 million) in recent months, but even that official supply didn’t satisfy the vast demand for the Trump crowd’s most recognizable product. Unauthorized sellers like O’Daniel do a brisk business of their own.

O’Daniel receives his goods by air cargo from a screen-printer in Phoenix, who designs and produces a constantly changing selection. Commission for vendors like him, paid by the distributor, increases based on performance and can jump from 10% to as much as 30%. On the best days — like a recent Trump rally in Seattle — O’Daniel said the crew can make $700 each in commissions. It’s good money for the young, transient team.

“They hire teenagers or millennials — whoever can do it really, because it’s a very specific lifestyle,” he said, estimating he drove 20,000 miles in the last month. “You can only do this at certain times in your life.”

And while the Trump campaign may be closing up shop, the demand for T-shirts goes on. O’Daniel is planning a 2018 trip to South Korea for the Winter Olympics, where he’ll sell products for the same distributor.

“I’ve never been,” he said. “I don’t have a girlfriend or kids. When else could I do something like this?”

Outside a rally in Charlotte, North Carolina, a man calling himself “Button Bill,” with a handful of teeth missing, oversaw several tables of pins, hats, scarves, flags, bumper stickers, and dolls.

Button Bill had a tracheotomy hole in his throat, which he covered with one hand when he spoke, first swallowing air and then answering questions. Bill’s been selling and distributing goods for 24 years, including a half dozen presidential campaigns, he said, back when “none of these guys were around,” he said, gesturing toward the other sellers, many of whom were people of color. “We used to have this on lockdown,” he said, “but because Obama is black they all found out about politics.”

The only campaign that could compare to Trump’s in terms of sales, other veteran dealers interviewed agreed, was Barack Obama’s in 2008. His election led to a new explosion in original and bootleg memorabilia. One swag manufacturer, the Political Mint, even solicited for international sellers for a speech Obama made in Prague, and created a spin-off business catering to fans of Bo, the presidential dog, in the wake of the selling spree.

Button Bill said that in his experience, whichever candidate sells the most wins the election, and Trump was this year’s chart-topper in knockoff sales by a long shot. Asked whether that meant Trump's seat in the Oval Office was secure, Button Bill said the candidate was “an exception” because “he’s a moron.”

Part of the reason Trump products sell better than Clinton items, Bill said, is Clinton’s much-mentioned three decades of public service: “Most of the older people already have their Hillary buttons.”

After Nov. 8, Button Bill said, he’ll be moving on to selling merchandise outside NFL games, Christmas parades, and, of course, the inauguration.

Glenn Wilcoxson, from Clearwater, Florida, described the cluster of vendors that follows the Trump campaign as “our own little mini farmer’s market,” where politics takes a backseat to commerce.

“Some of us are Republicans. Some of us are Democrats. Some of us are voting Trump. Some aren’t. It’s America,” he said.

Wilcoxson owns his own screen-printing business with his wife, Dawn, and, alongside their touring, the couple operate a modest online store. On their most successful day, the Wilcoxsons say they made $3,000 in two hours.

At a rally in Greenville, North Carolina, this fall, the pair arrived at the carpark across the road by 8 a.m., and made their first sale within 10 minutes. Both designers, they come up with original graphics and logos for the merch, they said. Their top items proclaim “Hillary’s Lies Matter.” Much the way liberals co-opted and riffed on “Make America Great Again,” their designs have twisted “Black Lives Matter” into new slogans — “Deplorable Lives Matter,” “Trump Lives Matter.”

When the couple spoke to BuzzFeed News in September, they had been on the road for two weeks, and said they would never knew where they’d be going next until the Trump camp decided. They watched his website by the hour.

As a supporter of Trump’s campaign, Dawn lamented that opportunistic new vendors — whom she suspects aren’t real fans — have begun crowding out the established sellers, operating in some cases without permits from the cities they visit.

"We produce everything ourselves but the flags,” she said. “They’re probably Republicans ‘til sundown.”

Robert Ball, 31, from Greenville, Tennessee, works in disaster relief, excavation, and demolition when he isn’t raising his five XXL blue bully pit bulls. Ball was working a stand at an October Trump rally along with his mother, Tammy Ball, 52, who said the family had been selling since August.

The Balls advertised cheaper prices since they support the campaign: $16 for a shirt and hat combo. Back home, they’ve been selling fireworks for 30 years. “We’re just small-business owners and entrepreneurs,” she said.

Danny Engels, from Charlotte, North Carolina, works with eight people across three crews, and said that even from the parking-lot perspective of the swag seller the country’s political temperature is rising. “Even in 2012, Obama versus Romney was never so heated,” he said.

Of the many Republican and Democrat crowds Engels has sold to, he said those who backed Bernie Sanders were his favorite. “The atmosphere was more fun,” he told BuzzFeed News. “These rallies are a bunch of yelling and screaming.”

When not out on the campaign trail, Engels sells other goods at events like the Super Bowl, the World Series, and pride parades. During the quieter parts of the year, he plays a lot of poker.

“I don’t support Trump,” he said. “I’m just supporting myself.”

Danny Harrison, 52, who was set up at a rally in Cleveland, said he’d been selling event gear for eight years with his fellow crew members for a distributor based in Ohio. Some of his co-workers were on their way to Florida, but Harrison said he preferred to stick to his home state and local rallies he could get to with ease.

“I gotta stay here,” he said. “I got an old lady. She’s not going for that being-gone-all-the-time.”

Back in her home state of Texas, Shannon Carpenter runs a janitorial service. But when a friend asked if she would go on the road for a month selling, she saw a chance for a change of pace.

At an event in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in October, Carpenter said she finds it hypocritical that, in an effort to sell more official merchandise, the campaign sometimes hassles hawkers. “Trump has always been prideful of capitalism, but they're running all the vendors off,” she said. “He can make money off people, but people can't make money off him.”

Vachary Hopkins, an African-American man from High Point, North Carolina, sold his stock of T-shirts, Hillary bobbleheads, shot glasses, and coffee mugs from a pushcart outside a Trump rally in Waukesha, Wisconsin, in September. Hopkins said he “wants change in the White House,” but seemed noncommittal toward Trump.

“If I were to vote today, I would probably vote for him,” he said. “Probably. He's an entrepreneur like I am."

“Culturally, we’re like a pack — like the Wolfpack,” said Derrick Clayton, a seller who asked to go by his middle name. “We look out for each other.”

In sleepy Cedar Rapids, Iowa, he and his crew set up in a parking lot as Game 3 of the World Series was underway. “After enough rallies, you get the strategy down,” he said. The team listed off some of the downsides of their long-running gig: bad weather on long, exhausting drives; protesters who flip over tables and carts; police who threaten to confiscate their merchandise; general fatigue from the grind.

During the political off-season, Clayton helps run a company called 341 Novelties that makes custom clothes and souvenirs for concerts, political gatherings, and sports events with “close family and friends,” he said. “That way we can trust each other.”

Leah Willoughby, 25, from Lexington, Kentucky, said in late October she had been selling for only about a month. She’d done events work in Ohio, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, but her sales were slow that evening in Cedar Rapids as security asked vendors to stay outside the fenced performance area.

“Sometimes they’ll let us in the gates so we can have better contact with people and it looks more legit,” she said. “This doesn’t look too legit.”

Still, Willoughby sold a handful of Trump tees based on the Harley-Davidson logo and one with an “America” design, resembling Budweiser’s when Anheuser-Busch temporarily renamed the beer “America” ahead of the election.

Asked whether selling political merchandise felt meaningfully different from selling at sporting events, Willoughby replied, “In a way.”

“It doesn’t mean anything when you sell for, say, a car company or sports team,” she said. Still, when the election ends, she'll take her wares to the next MLB All-Star events.

David Mack contributed reporting from Greenville, North Carolina; Ema O’Connor from Cleveland, Ohio; Dominic Holden from Waukesha, Wisconsin, and Canton, Ohio; and Katie Baker from Portsmouth, New Hampshire.