For most people, getting dressed for work is pretty simple: You select a shirt and tie, or put on an Oxford shirt and khakis... maybe, if you’re lucky, you throw on jeans and a T-shirt. For Dr. Inger Damon, getting dressed for work is a lot more complicated, requiring her to get her eyes scanned, take a shower, and change into a government-approved jumpsuit and gloves before stepping into a 20-pound protective suit — a roughly 15- to 20-minute process. Bathroom breaks? They’re pretty much unheard of in this line of work. If she did want to leave to take a break, she’d have to go through a chemical shower, a personal shower, and two changing rooms in order to decontaminate herself.

Damon, the director of CDC’s Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, led the agency’s smallpox work until a few years ago. During that time, a typical day at the office included a lot of time in a biosafety level 4 lab (BSL-4 for short) — or, as she calls it, a “box in a box.”

From the outside, the CDC campus in Atlanta looks fairly nondescript. Like any other office park, it’s got well-manicured landscaping, busy people in suits, and plenty of glass buildings. One of those buildings, however, houses some of the most dangerous threats known to humans.

Some have called it a “virus vault,” though those at the CDC don’t use that term. That’s because CDC’s High Containment Laboratory (HCL) contains more than just viruses. And it’s not, in the technical sense, a vault — though it’s pretty impenetrable.

Opened in 2008, the HCL houses four BSL-4 lab suites, capable of handling contagions for which there is no treatment or vaccine (think Gwyneth Paltrow in Contagion). While level 2 materials are moderately dangerous, level 4 are the most harmful and therefore require an intense emphasis on safety.

Only a select few laboratory staff have the proper credentials and experience to work with the most dangerous pathogens. Also known as “select agents,” these pathogens have been declared by the US Department of Health and Human Services or by the US Department of Agriculture to have the "potential to pose a severe threat to public health and safety,” and are therefore governed by a regulated tracking and inventory system.

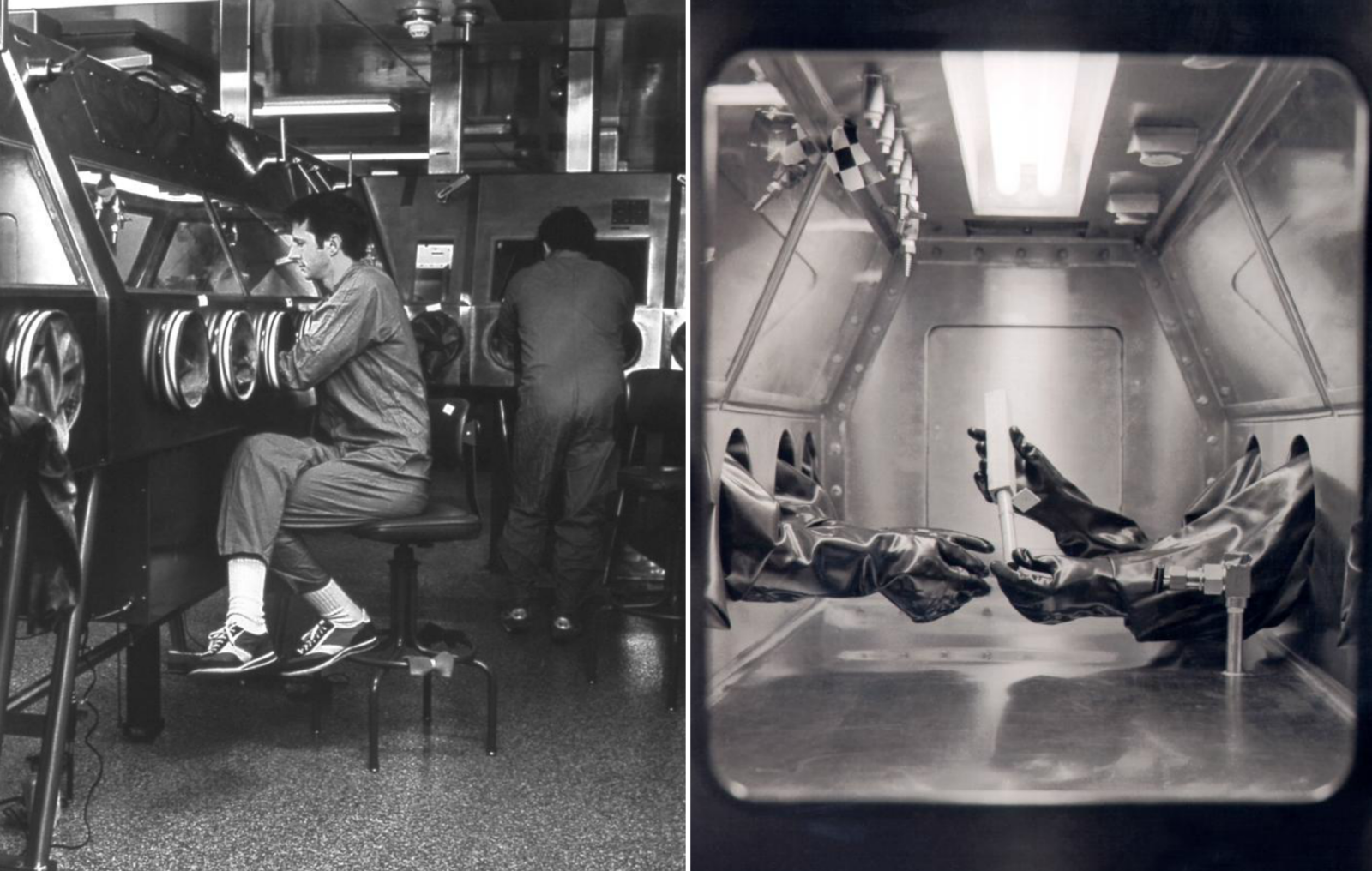

Entering a BSL-4 lab requires typing in a unique key code, undergoing an iris scan, and removing all personal clothing, jewelry, and accessories (with the exception of eyeglasses). Next, workers don clothing for the lab: a scrub suit, socks, and inner gloves. Then comes the "spacesuit” — i.e., a full-body, positive-pressure biosafety suit, which Damon said “pushes air out to prevent anything from coming in.”

The suit is so large it adds a solid two to three inches to anyone’s height, thereby restricting movement and making laboratory work even more difficult than it is already. With no air coming in, it also creates a dehydrating environment — which is not necessarily a bad thing, considering how difficult it would be to take a bathroom break.

The lab’s security features read like something from Mission: Impossible, specially engineered to prevent microorganisms from being disseminated into the environment. The walls are made of thick, solid concrete, designed to maintain pressure differentials and withstand natural disasters. In essence, they form a sealed internal shell — “to facilitate fumigation and prohibit animal and insect intrusion,” according to the CDC.

Floors are designed with a watertight seal. Laboratory furniture is simple, void of sharp corners, and covered in a nonporous material to allow for easy decontamination. Windows (if there are any) are shatter-resistant and sealed. Eating, drinking, smoking, handling contact lenses, applying cosmetics, and storing food for human consumption is, perhaps unsurprisingly, entirely off-limits. No phones are allowed inside the lab, but there is a computer from which scientists can access emails and files (though they’d have to do so wearing gloves that make typing a challenge). With the exception of the scientists themselves, who enter and exit the lab each day, nothing can get out.

With no air coming in, it also creates a dehydrating environment — which is not necessarily a bad thing, considering how difficult it would be to take a bathroom break.

“Any way the virus could potentially escape, there are at least two ways to prevent that from happening,” Damon told BuzzFeed. “The samples are kept in biosafety cabinets, there’s negative pressure in the room, doors are airtight and gasketed. There are multiple ways that, when air is coming out of the lab, it’s then purified and cleaned. And any waste products generated in the lab are autoclaved [i.e., placed into a pressure chamber to sterilize medical waste] and incinerated.”

Upon leaving the lab, workers step into a decontamination chamber, which showers a mix of chemicals over their suits to decontaminate anything that may be on the surface. From the chemical shower, they go through an inner changing room, where they take off the suit and everything worn beneath it. The clothing worn in the lab under the spacesuit is treated as a potentially contaminated material, and thoroughly decontaminated before being laundered. Next, lab workers must take a personal shower before entering an outer changing area, where they can then dress into street clothes.

Smallpox research wasn’t always conducted in such regulated quarters, however. Toward the end of the eradication campaign of the 1960s and ‘70s, the virus was worked with “on the bench” — that is, in the same manner that a scientist would work with other, less dangerous pathogens. This lack of safety procedures is “likely what led to a couple of lab-based infections near the end of the eradication program,” Damon said. “As it was being eliminated in many countries, the decision was made to only work with the virus in more restricted or contained environments.”

Though not all CDC staffers who work with dangerous pathogens do so in a traditional lab. Tara Sealy’s “office” is, more often than not, a forest or cave in Africa.

Sealy, a microbiologist with CDC’s Viral Special Pathogens Branch, works in the virus host ecology group. In other words, she studies how a virus is transmitted from an animal to a human. “We’re kind of trying to figure out what the reservoir host is for Ebola,” she told BuzzFeed. “It’s a big mystery how the virus is transmitted to humans.”

Her work uniform is slightly less complicated than those worn in a BSL-4 lab. “We take different precautions out in the field versus the lab, because we don’t have the big biosafety suit out in the field,” she said. Instead, she and her colleagues wear gowns and three sets of gloves (two latex, one bite-proof) with a PAPR (she calls it a “papper”), a personal air-purifying apparatus attached to a hood.

“With the suits we wear in the field, there’s no air pressure. It’s like a hood with a hose connected to a battery pack that circulates air in your hood,” she said. “You could get a hole in that hood part but the pathogens we work with are not airborne. It would be more of a problem if I were to get bitten by a bat. But there are protocols to decontaminate and let your supervisor know. I know that I’m safe.”

As intensive as these modern-day safety procedures are, they aren’t without their faults. Earlier this year, CDC temporarily halted work in its high-security labs over concerns that the air hoses attached to body suits were not certified for breathable air. A spokesperson for the organization said it made the announcement out of an abundance of caution, but it wasn’t the first time lab workers had been faced with safety concerns.

As USA Today reported last year, four suited-up CDC scientists were confronted with a “series of equipment failures” when their lab’s decontamination chamber (the powerful chemical shower that completely disinfects the outer surface of the suits) stopped working in 2009. No one was hurt in the incident, but it did raise a number of red flags and news of the incident came fresh on the heels of congressional hearings regarding CDC’s handling of anthrax, Ebola, and a deadly strain of bird flu. Because many of the organization’s safety issues were publicized only after USA Today requested reports under the Freedom of Information Act, critics argued that CDC was attempting to keep those mishaps under wraps.

In a separate incident in 2008, a bird flew into a high-voltage transformer on the CDC campus, causing the primary power supply for BSL-3 facilities to fail. The labs ran on battery power for about an hour before the situation was rectified. The CDC won’t confirm which specific safety systems require electricity, citing that it's sensitive information. But the organization does say that, in the off chance both the electricity and generators failed, no safety systems would be compromised and workers would be able to exit the labs.

As intensive as these modern-day safety procedures are, they aren’t without their faults.

Despite these incidents, Damon and many of her counterparts express their confidence in the safety measures at high-containment laboratories such as the CDC’s. As Damon noted, “There are multiple ways to prevent infection in the lab environment.” Because smallpox was successfully eradicated in the US, vaccines haven’t been routinely administered since the 1970s. Damon and many other scientists who study the virus, however, have been vaccinated.

Samples of smallpox are found in only two places in the world — at least, to the public’s knowledge. “One is at CDC and one is in Russia [at the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology in Koltsovo],” Dr. Selim Suner, a professor of emergency medicine, engineering, and surgery, told BuzzFeed. “Both the US and the former Soviet Union had biological weapons programs and smallpox was one of the big players in that because it is so readily communicable. Of course, there may be classified information regarding other smallpox repositories that I’m not privy to — and, even if I was, I certainly couldn’t talk about it.”

Outside of the two “official” smallpox repositories, though, other samples have been found — rather accidentally, it turns out. “A few years ago, there was a group of researchers cleaning out a large refrigerator drum at the NIH [National Institute of Health],” Damon recounted. “They came across a box that hadn’t been opened or used for years, and they realized that the box included some vials that contained variola virus [smallpox].”

The samples were old but, as Damon noted, still alive — and therefore very dangerous. “Even though these specimens had been stored in the 1940s and 1950s, we could still identify materials that were spreadable and could grow.” Fortunately, no one was hurt, and scientists from the CDC as well as the FBI conducted a follow-up investigation and brought the samples back to the high-containment lab.

Samples of smallpox are only found in two places in the world — at least, to the public’s knowledge.

Dr. Mark Kortepeter, the former deputy director at the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, previously worked with Ebola in a high-containment laboratory setting at USAMRIID. Like Sealy, he worked with animals — in this case, nonhuman primates — which can be unpredictable. “Obviously when you’re working with a potentially deadly agent, you have to be vigilant,” he told BuzzFeed. “But nonhuman primates can be very vicious — they can bite, they can scratch. You have be a bit more cautious, move slowly, don’t make rapid movements.”

Ebola is an especially unique contagion, he explains, in terms of its ability to spread within a hospital: “If you think about a respiratory disease, it’s of course spreadable. But with Ebola, you have to worry about the fact that the virus is teeming in the blood. Anyone touching any bodily fluid could be at risk. There’s no room for error.” Which is why, he surmised, several health care workers have been infected with Ebola while dealing with patients.

Asked whether he panics at the onset of a cough or sore throat, Kortepeter said, “If you have a cut or something or your suit doesn’t maintain positive pressure, you might get a little nervous. Of course, it’s always in the back of your mind.”

One thing that makes Kortepeter slightly more nervous? Determining what could be the next smallpox, Ebola, or Zika. “First of all,” he said, “we’re not good at predicting what comes next. Physicians are taught, ‘If you hear hoofbeats, think about horses, not zebras.’ So when something brand new comes along, we aren’t necessarily prepared. SARS came out of the blue. Ebola — who would have ever thought we would have had such a large outbreak? And then Ebola dies down and suddenly Zika virus crops up.”

The chances that a nefarious organization could get its hands on a virus like smallpox, in order to weaponize it, are incredibly slim, considering the measures in place at high-containment labs. However, there is technically a way around that. “At this point, the genome of smallpox is known,” Suner said. “So if someone could get their hands on that, they could possibly re-create it in a sophisticated lab. But I don’t think terrorists are at that stage.”

People have had success with similar experiments in the past, though. “Certainly the Soviet program was very advanced, weaponizing things like anthrax, smallpox, coding it to make it more readily spread in the atmosphere,” Suner said. “They had a very robust program.”

So robust, in fact, that it led to an outbreak in 1979, when Soviet scientists accidentally released anthrax spores from a suspected biological weapons facility in Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg). A former deputy chief of the weapons program has since claimed that the release, which killed at least 64 people, was caused by workers who forgot to replace a filter in an exhaust system.

“That sort of portends what could happen if there was a large release today,” said Suner. “In this case, they noticed it rather quickly, so they plugged the hole. But you can imagine what would happen if there was a crop duster [full of anthrax] that went over New York City.”

Still, the physicians and scientists who work closely with dangerous pathogens are confident that, should the need arise, the response would be more than sufficient to ensure another smallpox-like outbreak doesn’t occur.

“Infection control is a skill in and of itself,” Kortepeter said. “Ebola kind of caught us a little by surprise in that way and it took a while to sit back and rethink whether we have the proper procedures in place to respond. Once the word gets out, we’re usually pretty good at adapting, though. The medical community is is ready to step up to the plate when the time comes.”

CORRECTION

Dr. Damon is the current director of the Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology. An earlier version of this post misstated that she is the former director of this division.

This week, we're talking about preparing for and surviving the worst things imaginable. See more Disaster Week content here.

If you liked this story, you might also like:

• How To Survive A Super Typhoon

• What To Expect When You're Expecting The Collapse Of Society As We Know It