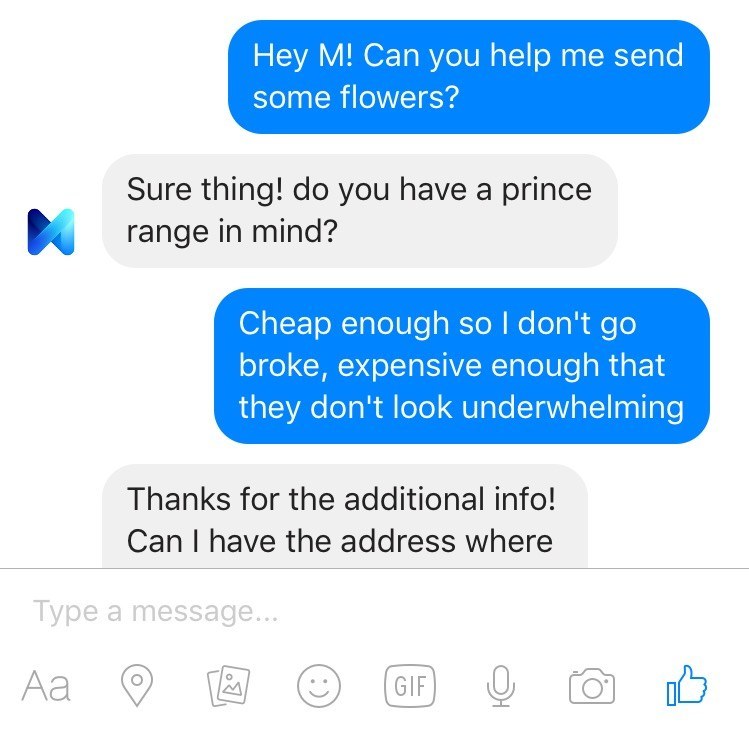

Someone sent a Starbucks Pumpkin Spice Latte to my desk at work. Which was weird because I didn't ask for it. And even weirder because it came from some of the most sophisticated technology in the world: M, the artificial intelligence–driven virtual assistant Facebook is building into its Messenger app. AI, I thought, was supposed to outsmart and kill us, not send autumnal coffee beverages. So forgive me for being a little suspicious of the grande red cup at my desk.

I’ve had M on my phone for about a month now. And while it's currently still just an experiment, there's a strong probability that it's coming to your phone, too. Before it becomes pervasive, I wanted to understand it, and ask questions of it. I’ve pushed it incredibly hard. I’ve had it research and book a flight for me, reduce my cable bill, get Star Wars tickets, send free coffee, write a song, and, yes, even draw pictures. Many pictures.

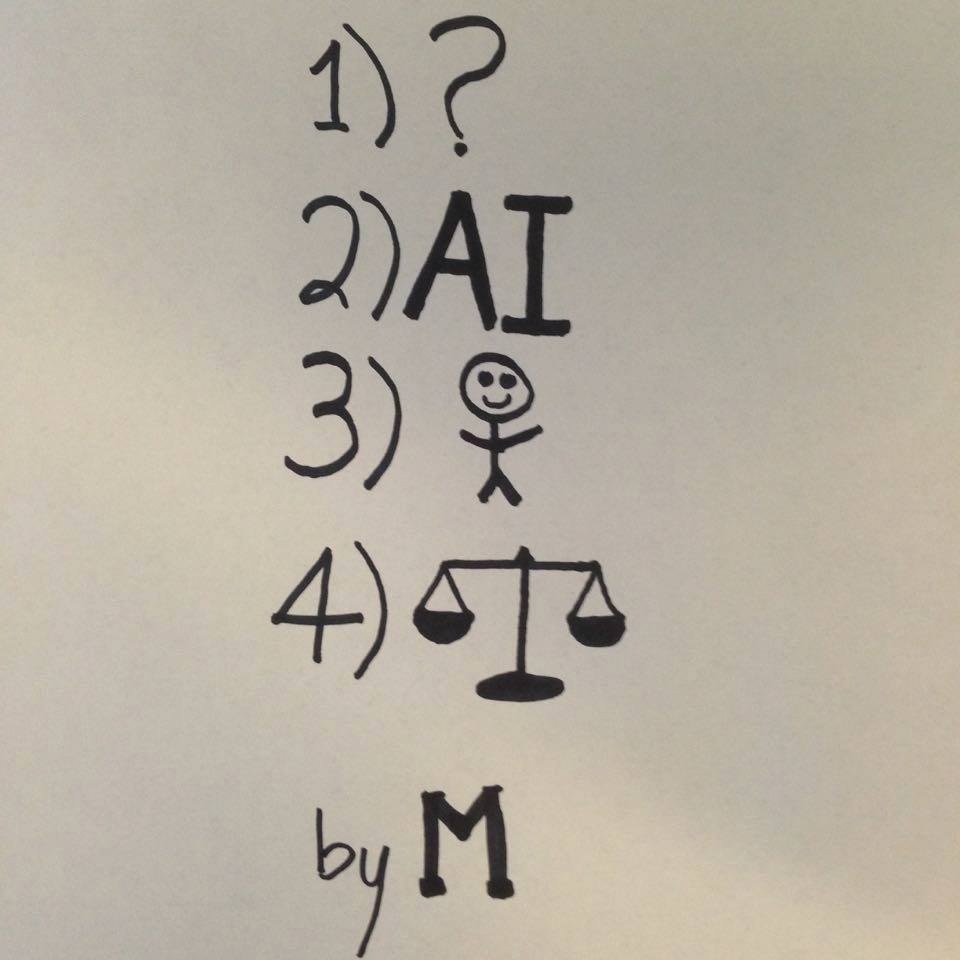

But while I got the art of M, very literally, I wasn't so sure about the science of it. Nor have I been sure of Facebook's motivations, or the ethical implications of using M at all. Every time I asked M who or what I was talking to, it offered the vague line: “I’m AI, but humans train me.” This was frustrating. If M was mostly AI, then what I was witnessing was an astounding technological innovation, something that could change the way online business works — there’s plenty of money to be made when you become the place people go when they want to buy stuff (see: Google). But that works only at scale. If M were really an ordinary human sitting at a console with a calculator, then I was a dupe, not to mention a bit of an asshole for making real people do all this stuff for me. And so, after weeks of wondering, it was time to meet the wizard.

A few minutes after 1 p.m. on a recent Thursday afternoon, David Marcus, the man who knows all of M's secrets, walked into a bright conference room in Facebook's Menlo Park, California, headquarters. I already knew what Marcus, Facebook’s vice president of messaging products, looked like, since M had drawn me a portrait of him before our meeting.

Marcus didn’t waste any time getting into the big questions about M, directly addressing how much of it was AI and whether it could scale. Throughout the conversation, Marcus held a firm line: Yes, he repeatedly claimed, M can scale. And though there are humans “trainers” involved, he said there is plenty of automation already in place. Asked if he disputed that M is, as some have asserted, a mechanical turk, or a person that pretends to be a machine, Marcus replied, “Yes. Fiercely.”

Marcus described what he claims is the process behind the scenes when people communicate with M. After someone sends M a message via Messenger, “a response is actually formulated by the AI engine, and the trainers have the ability to let that response go, or one of those responses that are suggested go, or write a completely different one, or do something else,” Marcus said. The AI, intriguingly, always takes a stab at the answer first.

The trainers are a group of a few dozen human contractors working in Facebook’s headquarters. These humans, as Marcus explained it, review each of the AI’s responses and decide whether they’re good enough to pass along, or whether they need revising. When the trainers revise, the AI watches and learns: “With every single one of these interactions, that data is fed back into that AI instance that will then use the data to learn how to automate more and more answers or how to get better and better at those things,” Marcus said.

Just six weeks before my meeting with Marcus, the AI couldn’t formulate a good response when someone tried to order flowers through M, he explained. But now it can. “Right now, you can actually go through most of the process of ordering flowers — and I’m not saying that it’s fully automated, because trainers will still validate the possible responses that the AI is suggesting — but the quality of all of those suggestions are actually getting really, really high.”

M’s AI will learn to automate more processes by watching its trainers go through different scenarios over and over, and then understanding how to mimic them. Today’s flowers might be tomorrow’s car rental. “Gradually, vertical after vertical, we can actually get better. And we can also determine, OK, maybe we need another 10,000 requests or 50,000 requests or 1 million requests of that vertical to actually get to a good place from an automation standpoint. Then we can decide whether it’s worth pursuing it or not,” Marcus said. I asked about the tools M's trainers use. Marcus said they are Facebook's "secret sauce.”

Oren Etzioni, CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, told me that Facebook’s process makes sense and can work. “Is this plausible? The answer is yes,” he said. “This is a very sensible and interesting approach.”

GoButler, another virtual assistant that employs a combination of humans and AI, has already reduced its staff of contractors from 60 to 40 thanks to process automation, according to its CEO, Navid Hadzaad.

Marcus said he’s optimistic M can be made available to a broad user base, but that it won’t happen overnight. “I think we have a good chance [at scaling], otherwise we wouldn’t be doing it,” he said. “It’s going to be hard work and it’s going to take a long time.”

A Picture’s Worth

Ordering flowers is one thing, but the picture drawing, song writing, and latte gifting seem impossible to automate. “Clearly, over time, we’re going to have to decide [what to keep],” Marcus said. “In this very early phase, what we want to understand is what people will ask.” Keeping things wide open, Marcus said, allows Facebook to measure what people want and how long the tasks take. And some crazy-sounding tasks might stick around if there’s enough demand and value.

I pressed Alex Lebrun, the former CEO of Facebook-acquired Wit.ai, who now runs the AI team behind M, on M’s limits, specifically focusing on the pictures M draws. I had asked M to draw a picture of my brother, which Lebrun knew about, and wanted to know if that capability would eventually go away. This was, after all, a robot engaging in creative activity. Or at least: a person teaching a robot how to make art.

“Nobody asked this before, so there is no way the AI had any clue about that,” Lebrun told me, of the picture drawing. The trainer drew the photo in this case, Lebrun said, but that doesn’t mean the task can’t eventually be completed by AI. “If we give a few hundred examples like that to our AI research team, they’re able to build a network that will do it,” he said, laughing. Developing something like this would take a good deal of time, but Lebrun wouldn’t rule it out. (You could make a case that Google's neural network is already capable of doing something similar.)

“Everything is possible,” he said. “Let’s look at what happens, and when something becomes frequent, the AI will learn to do it, and then it will be scalable.”

This, of course, is Facebook’s official line, and it’s impossible to verify without seeing it M’s AI and its trainers in action.

Etzioni, presented with this claim, said that while flowers are plausible, acting as a full-blown concierge is beyond the capabilities of AI in the near future. “They have already a subset of the concierge's abilities,” Etzioni said. “Over time, as they see more examples, that subset will grow and grow. But I'm very comfortable saying that if we check in a year from now, despite the fact that Facebook and M have the capability of processing hundreds of thousands of requests, they will not have a program that's on par with a real concierge, because of the complexity of it and the open-endedness of it, and the nuances.” Simply put: It's going to need to keep the human trainers in the near-term.

Marcus and Lebrun repeatedly stated that it will take a long time to get M where it needs to be. But they expressed faith in the underlying technology's ability to get there. “There have been a lot of AI breakthroughs in the last decade and we’re lucky enough to have a team that has been at the origin of a lot of those breakthroughs,” Marcus said. “We build a deep neural net that actually learns from these things, a deep learning neural net, and it just works."

Marcus isn't kidding about the breakthroughs. The field of artificial intelligence has experienced periods of dramatic slowdown, known as "AI winters," with the most recent dark period occurring in the early 2000s. These slowdowns, largely the result of lost faith in the technology's ability to back up its researchers' claims, set the field back more than once, costing it years of funding and human power. But the past decade is widely seen as a comeback period for AI. Which is why something like M, for the first time, actually seems realistic. And it's worth noting that virtual reality, which not long ago seemed out of reach, has gone through similar fits and starts but is now beginning to see widespread deployment.

Underneath the hood, M is driven by a combination of basic automation and “deep learning” technology, artificial intelligence that can draw inferences of someone's intent and make suggestions and plan actions based on it after being fed a large amount of data on similar or related examples.

The trainers, of course, are also a key component. M’s trainers, Lebrun said, are a blend between a customer service representative and AI jockey. Most have college degrees, he said. And they don’t get upset when the AI learns how to do tasks they were previously handling themselves. “There is so much work to do before it’s completely scaleable,” Lebrun said. “The trainers don’t complain when the AI does something good. They are happy. It’s less work for them.”

Though the trainers’ mission may seem at odds with their long-term employment prospects, Marcus indicated they shouldn’t go looking for other jobs quite yet. “There’s no configuration under which there are no humans involved with that service,” he said. “Fast-forward a couple of years from now where, say, a vast majority of the requests are automated, you’re going to still have cases where you’re going to need human intervention.”

M, in some ways, is already scaling back. It once drew pictures of photos, now it won’t. It used to sign its pictures “by M,” but that’s done too. And there are no more free lattes.

Do You Know Me?

M’s boundaries aren’t all technological. The examples referenced above actually seem to be more due to a reluctance on Facebook’s part to place M in risky situations. M won’t do anything illegal, understandable enough, but it also won’t direct you to an abortion clinic, or even find you results for optometrists on Yelp. It will not draw pictures of celebrities or “specific people.” And it seemed to back away from sending me the top image on Imgur every day, instead sending one of the most popular. After a request from a colleague, I asked M to send me tentacle porn, and it shut down for a number of days. M said the shutdown was due to technical difficulties. Maybe I fried its circuits.

Asked about M’s limits, Marcus said the company was being very careful. “If you’re a startup, and you have issues with things, you can get away with it. If you get to the scale we’re at, you can’t. So we just need to be a little more cautions."

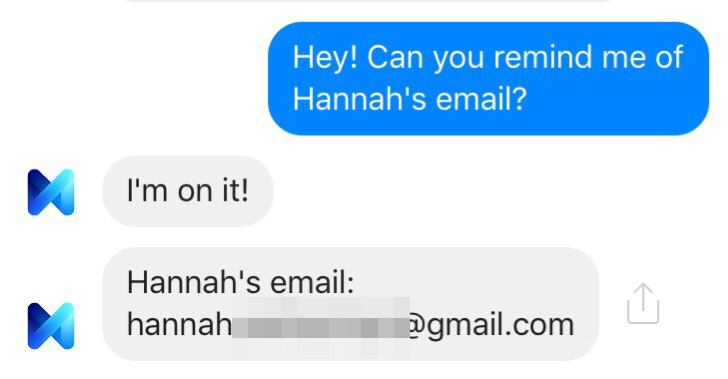

When M does things you ask, it doesn’t seem to forget. I asked it to store email addresses of my friends, for instance, and it can spit them out on command, and send calendar invites to them when I mention their first name. M has my credit card information, so when I tell it to buy things, I just need to hit “get” and “pay” and it’s off to the races. M knows my home and office address, so when I tell it “ship to my house,” it knows exactly where to direct the package. M knows the names of my brothers. It knows what sports teams I like. The list goes on.

What M is doing, however you want to label it, is building a database of me. I’m giving it more definitive information about myself than I’ve ever handed over to a company, and its knowledge about me will only grow. In 20 years, M could very well know me better than my friends. If we played the Newlywed Game, I suspect M would do quite well. But what it's learning are my preferences and the facts of my existence. Not who I am. It might know who I am friends with, but it could not understand, for example, the basis for those friendships. It couldn't find me a new friend.

“I reject the notion that the AI really knows you that well,” said The Allen Institute’s Etzioni. “If you go to Amazon or Netflix or any of these product recommendation technologies, often the recommendations are way off the mark. They're not terribly sophisticated.”

Marcus said he viewed the data you give to M as a trade-off. “I think that the equation to me is if a service provides value to you that is greater than the value of the data that you share, then people should be fine with it — at least that’s the way I look at things,” he said. “Yeah, sure, I provide the town I live in. But that will enable me to get services tailored to where I live rather than on the other side of the world. Is that a fair bargain? Sure.”

“It makes such a great headline to talk about all these things,” Marcus continued, “but the reality is people here are very well-intentioned and care deeply about people’s privacy.”

The Future

Facebook is putting a boatload of resources into AI. It hired, for instance, more than 50 researchers led by AI veteran Yann LeCun. These researchers can make anywhere from mid-six to seven figures, according to one report. It acquired AI company Wit.ai in January. It is paying the full-time employees and contractors who work on M. And it is an area of focus for Marcus and other top executives in the company, including Mark Zuckerberg (who Marcus said came up with the concept for M).

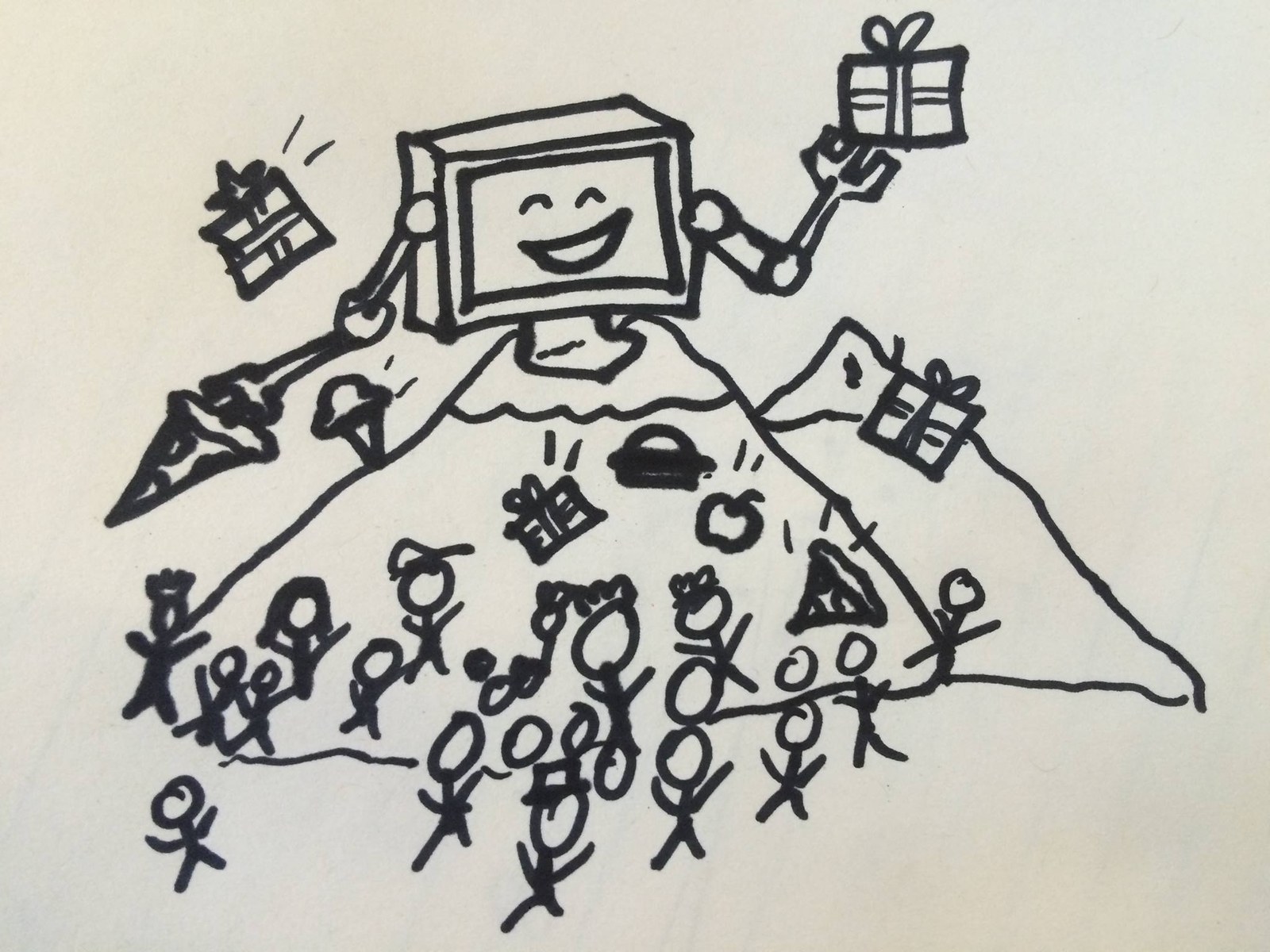

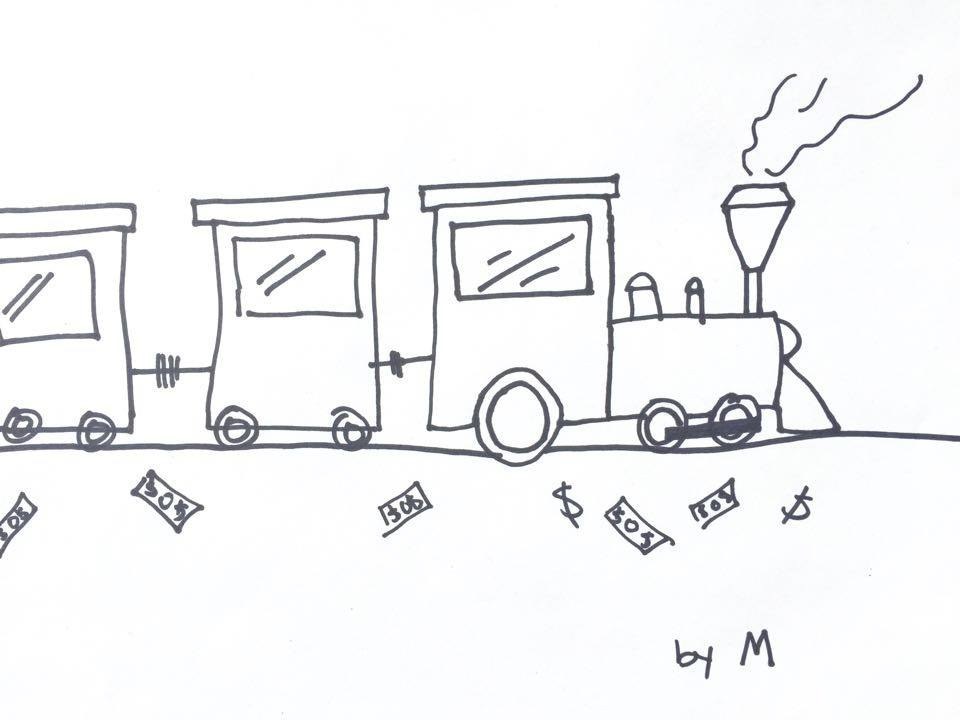

To understand why that is, and the economic opportunity of M, think of it as a possible replacement for a Google search. Google makes its money by matching businesses with people looking for services similar to theirs. Search for flowers, for instance, and you’ll get a bunch of ads for flower shops. But if that query goes over to M, then Facebook stands to make the money instead.

Tens of billions of dollars a year are therefore at stake for the companies that can best capture our “purchase intent.” Google, the master, knows this. It’s put hundreds of millions of dollars into AI efforts of its own, including the $400 million purchase of the London-based artificial intelligence startup DeepMind last year.

“This is a multibillion-dollar arena,” Etzioni said.

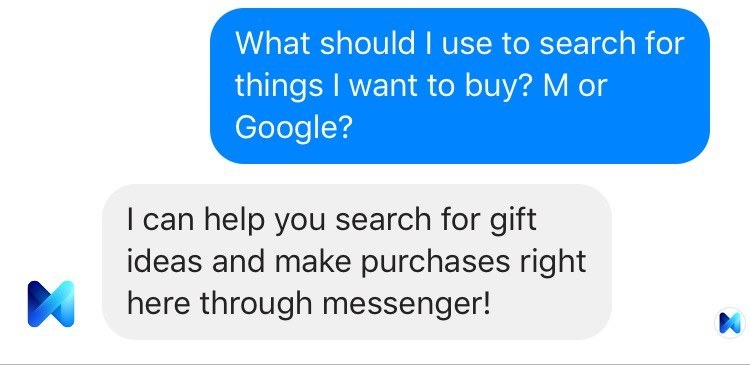

Marcus wouldn’t directly answer the suggestion that Facebook was after Google’s business. But he did say that M could match people looking to buy products with businesses that offer those products (otherwise known as Google’s value proposition to advertisers). “If you want to buy flowers, is there a flower provider that can use an API that we provide to actually fulfill a request?” Marcus suggested, opening up the possibility that businesses will eventually get to plug directly into M. “That’s also a form for them getting new customers and it’s an entry point, and they might be willing to pay for that.”

Google’s search business also sits largely on top of the web, a potential liability given that today’s mobile-addicted population is spending more and more of its time within apps. This amounts to another opportunity for M and Messenger, since the app is installed and active on over 700 million phones.

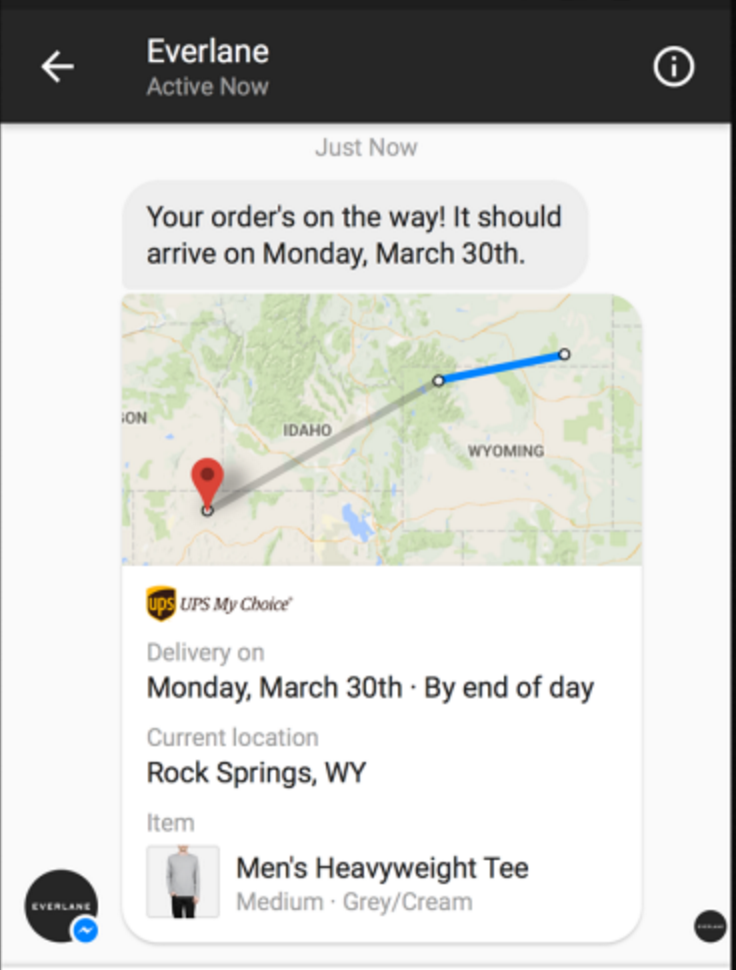

“We’ve been able to prove that there’s a ton of value for businesses to have a thread open with their customers inside of Messenger,” Marcus said. Messenger, for instance, recently introduced a number of businesses to the product, who are using it to conduct customer service and other business activities. Marcus said clothing retailer Everlane, for example, offers to send you a receipt through Messenger after you purchase an item. Along with the receipt comes a photo of that item and a bubble that updates with its shipping location thanks to integrations with the U.S. Postal Service, UPS, FedEx, and more. If you write back that you want another T-shirt, for instance, but in black, Everlane can handle that too.

“When I say black one, they know I’m talking about a T-shirt, what model of a T-shirt, what size, where to ship it. They have my payment details,” Marcus said. “It’s the good old form of commerce and relationships that we used to have 100 years ago, or 50 years ago, that’s now lost since the web era.”

KLM, an airline, is also working with Facebook to build itself a presence within Messenger. Think about getting a Messenger notification when it’s time to check into your flight, Marcus said. Within Messenger, he said, you could get a message with a check in button and, when you tap it, your boarding pass. “No authentication, always in context, always the right information when you need it at your fingertips,” Marcus said.

Add these examples together, and you can see how Facebook Messenger could potentially replace a bunch of other apps. “We actually think that for certain things, a [messaging] thread is a better version of an app in this new world,” Marcus said.

This is where M could get very interesting. If Facebook offers businesses the technology behind M, it would make it even more enticing for them to conduct business through Messenger. Eighty-nine percent of businesses will compete mostly on customer experience by next year, according to research company Gartner, so if M's technology could help them improve that experience, they'd be fools to turn it down. This could turn Messenger into a hub for online commerce, with a little M sitting inside each business. The money that may follow, tied to purchase intent, could be very significant.

Marcus wasn’t shy about the possibilities when asked if M’s AI could be applied in other scenarios. “Everything we’re doing with M is enabling us to learn how to extract intent from natural language better,” he said. “If we can help our partners extract intent and then do something with it, then we’ll help them do that.”

If and when that day comes, M will already have served a critical function. Though Facebook, it appears, would like to see it end up in your hands too, not just mine.

UPDATE

Most of M's trainers have college degrees. In a previous version, a Facebook manager misstated their education level.