This is part of a BuzzFeed News Investigation. Other main stories in the series include:

Detective Guevara's Witnesses and related video

Roberto Almodovar Finally Walks Free

Justice Delayed

It's Cold Outside

Jose “Kool-Aid” Melendez had been shut in an interview room in Chicago’s Area 5 police station for hours answering one question after another about cars he owned or had owned when, according to Kool-Aid, Detective Reynaldo Guevara suddenly began to beat him.

Where’s the car at, Kool-Aid said the detective demanded to know.

Kool-Aid repeated that he’d sold it.

Where’s the car, he said the detective pressed, rising from his chair.

I sold it, Kool-Aid said again.

He said Guevara, a husky 19-year veteran with thick, black hair and rings on his fingers who has since been accused of framing more than 50 people for murders they say they did not commit, drew his fist back and punched Kool-Aid in the skull.

Police had pulled over the 27-year-old with short, dark hair and a goatee as he drove to the gym on the evening of May 30, 1995. The officers asked him about the black Buick Park Avenue he was driving. They claimed it had been used in a drive-by murder a week earlier.

Kool-Aid explained that a week earlier he hadn’t yet owned the car. He’d traded for it recently with a guy he knew from the neighborhood. As for the murder? Kool-Aid knew nothing about it.

Now Guevara was demanding to know about another car — an old, gray Oldsmobile. Kool-Aid said he had sold it six months earlier, but that didn’t seem to matter to the detective. Guevara said this car, too, might have been used in a second recent murder.

Kool-Aid, confused, said that neither car was in his possession on the nights in question. Yet Guevara kept asking him about the gray Oldsmobile.

Tell me the truth, Kool-Aid said Guevara demanded between punches. Tell me the truth.

The detective was winding up to take another swing, Kool-Aid said, but appeared to flinch, grabbing onto one of his rings.

Kool-Aid, a former amateur boxer, recognized the expression. He figured Guevara had hit him so hard he’d broken a knuckle.

Kool-Aid’s interrogation was over. But his ordeal of being accused of a murder he hadn’t committed was only beginning.

DETECTIVE GUEVARA’S WORLD

A reckoning has begun for Guevara. Following a BuzzFeed News investigation in April, prosecutors dismissed charges against two men who had been jailed for 23 years for murders they didn’t commit. Three more dismissals have since followed. In all, courts have overturned the convictions of 12 men who said the detective framed them. At least 16 more are fighting to overturn their convictions on the same grounds; three have pending federal civil rights lawsuits. The Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office said it is reviewing more of Guevara’s cases to determine whether charges against other imprisoned men should be dismissed. Earlier this month, a Cook County Circuit Court judge accused Guevara of telling “bald-faced lies” while under oath in a case involving two people he helped send to prison for life.

The night of May 30, 1995 — the night police dragged Kool-Aid and his Buick into the Area 5 Violent Crimes Unit — offers a one-night case study in how Detective Guevara, and the system that enabled him, flouted fundamental police procedures over the span of many years, letting murderers roam the streets while condemning the innocent to decades behind bars.

In recent years, courts have overturned the convictions of 12 men who said Guevara framed them.

Faced with two unsolved murders committed three days apart that had no obvious connection to each other, Guevara and his longtime partner, Ernest Halvorsen, seized on the vague description of a Buick given in one shooting. Working off that description, they eventually accused two men of murder.

Kool-Aid — who worked two jobs to support his 3-year-old daughter — was charged with killing a young man on Fullerton Avenue. He was acquitted.

The other accused man from that night, Thomas Sierra — a 19-year-old who’d bounced from relative to relative for two years since the death of the grandmother who raised him — was charged with murder in a drive-by shooting near Logan Square. Sierra was convicted — despite the fact that one witness testified at trial Guevara had told him whom to pin the murder on.

A review of Area 5 police reports from May 30, 1995, along with interviews with key players from that night and a review of trial testimony, shows just how many liberties Guevara and Halvorsen took while building their cases against Kool-Aid and Sierra. Between the two of them, they are accused of beating a suspect, disregarding the qualms of several witnesses, and, according to their reports, failing to follow up with others who saw or heard the actual murders. The detectives' theories don't make much sense when lined up against the evidence. Indeed, the case files reflect how their operating theories morphed from one to another without explanation, a bit player in one crime becoming a suspect in another without any previously known connection to it, and witnesses who helpfully turn up just as the cases are about to go cold, with crucial information leading to the supposed killers.

But the detectives did not act alone. Supervisors signed off on police reports despite glaring inconsistencies or noticeably thin evidence, and prosecutors filed charges and presented that dubious police work to judges and juries, contributing to an entire system in Chicago that violated the most basic safeguards designed to ensure justice.

Kool-Aid said he has spent the last 22 years wondering how he was accused in the first place.

Sierra has maintained his innocence since his arrest and through his subsequent 22-year prison sentence. He served his time and was released last month. He is still trying to overturn his conviction, and he has accused Guevara of framing him.

Central to Sierra’s claim, his attorneys told BuzzFeed News, will be a close examination of what happened in the interview rooms on the second floor of the Area 5 headquarters on Chicago’s Northwest Side, which covered a predominantly working-class Latino neighborhood, on the night of May 30, 1995.

Guevara and Halvorsen did not respond to requests for interviews, nor to detailed questions sent to their homes, and their attorneys, through a city spokesperson, said they would not comment. In court, Guevara has asserted his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination at least three times in recent years when asked about whether he framed people.

The city of Chicago and its police department also declined to comment.

A spokesperson for Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx said that Sierra’s conviction is currently under review.

Sierra’s lawyer, Steve Art, told BuzzFeed News the police were “preying on a community that has almost no way to fight back effectively. They’re taking a generation of that community’s kids away.” He added, “That’s terribly destructive not only for the fabric of the neighborhood — there’s a serious cost in human lives. There are dangerous killers on street, and innocent kids are in prison serving their sentences.”

TWO MURDERS, NO SUSPECTS

The first murder occurred May 20, 1995. Ruben Gonzalez — a 21-year-old self-taught auto mechanic whose skill with cars included knowing how to steal them — had been in his Pontiac around 4:20 a.m. parked next to a silver car with two men in it. Ron Malczyk, a beat officer cruising by, recognized the pair in the silver car as members of the Imperial Gangsters. Malczyk continued his rounds, but a few blocks later someone flagged him down. Gonzalez’s Pontiac had just crashed into a light pole on Fullerton Avenue.

Malczyk rushed back and saw Gonzalez hurtled halfway onto the street, his body riddled with bullets. The shell casings were a block and a half back, suggesting that Gonzalez was shot and then tried to speed away.

Malczyk rushed back and saw Gonzalez hurtled halfway onto the street, his body riddled with bullets.

As Malczyk tried to secure the scene, the two men in the silver car circled back to Gonzalez’s Pontiac. The officer told them to wait so he could talk to them, but they fled, according to the first reports from the scene.

Detectives later canvassed the neighborhood around Fullerton Avenue and talked to a man in an apartment above the scattered bullet casings. He said he heard the shots and looked out his window to see two young Latino men running through an adjacent alley. He might be able to identify them if he saw them again, he told the detectives.

The second murder took place three days later, on May 23, 1995, about three blocks away, near the Logan Square Monument.

Three members of the Latin Kings gang were driving when they noticed a car that seemed to linger too long at the stop sign ahead of them.

The waiting car looked to be a dark Buick Park Avenue. As the Kings approached the stop sign, Jose “Macho” Melendez (no relation to Jose “Kool-Aid” Melendez) was behind the wheel, with Alberto Rodriguez riding shotgun. They saw a passenger in the Buick cupping his hand into the shape of a C — the gang sign for the Kings’ mortal enemies, the Spanish Cobras.

Macho hit the gas. The Buick followed. Then the front passenger in the Buick opened fire, killing 24-year-old Noel Andujar.

Between the bullets, the panic, and the dark, the most Macho and Rodriguez could give police was a description of the car: a dark blue or black Buick Park Avenue, short body, with custom wheels and tinted windows, and the barest descriptions of the three men in it.

A REMARKABLE DEVELOPMENT (PART 1)

Detectives Guevara and Halvorsen were assigned to investigate the first murder. Who had shot Gonzalez in his Pontiac on Fullerton Avenue?

Malczyk, the beat officer who had tried to talk to the two men in the silver car, went through department photos of suspected gang members, but he was unable to pick anyone out.

A natural next step might have been to visit the man in the apartment, the one who had told cops that he saw Latino men running through the alley right after the shooting. But if Guevara and Halvorsen — or any other officer — spoke to him a second time, there is no record of it anywhere in the police files.

Got a tip? You can email tips@buzzfeed.com. To learn how to reach us securely, go to tips.buzzfeed.com.

Those files contained no additional tips. And in the days that followed, no leads or breaks in the case appeared in the reports.

The Fullerton Avenue case looked like it could linger unsolved, perhaps forever. But these were the cases — the seemingly impossible ones — that Guevara and Halvorsen had developed a reputation for solving. Some have alleged it was because they would stop at nothing, not even the truth, to close them.

Then, the Logan Square murder took place.

It was just after 10:30 p.m. when the police scanner broadcast an alert for a dark Buick Park Avenue, the one that witnesses told police had opened fire near the Logan Square Monument.

Thirty minutes later, Guevara and Halvorsen filed startling new information. It was about the other murder — the crashed Pontiac on Fullerton Avenue — that they were charged with solving.

Why, given how important this information would be, hadn’t any reports mentioned it?

The new information was game-changing. Guevara and Halvorsen said Malczyk, the beat officer, had told them that the guys in the silver car didn’t actually speed off, as he had initially told responding officers. Instead, Guevara and Halvorsen reported, the men in the silver car took the time to tell Malczyk important information about the killers. They were members of the Orchestra Albany gang, the detectives said Malczyk had told them. And, more crucially, the killers were driving a dark Buick.

There were some oddities about this sudden revelation.

Why, given how important this information would be, hadn’t any reports from the night of the Fullerton Avenue murder mentioned it? Why didn’t Malczyk tell anyone else? And why would Guevara and Halvorsen sit on the information for three days? The police reports do not say.

When contacted by BuzzFeed News and asked about the omitted details, Malczyk responded, “Did they once-upon-a-time me?” — Did they make it up? “It wouldn’t be the first time,” he said, then declined to comment further.

Guevara and Halvorsen also added another new piece of information: they said knew of a gang member who had recently been seen driving a Buick and who happened to know the victim in the first murder, the one on Fullerton Avenue.

There could have been hundreds if not thousands of dark Buicks in Chicago at that time, but nonetheless, Guevara and Halvorsen advanced a new hypothesis: The two murders were connected.

“It appeared possible,” Guevara and Halvorsen wrote in a report May 30, that after the first murder, on Fullerton Avenue, “members of the Imperial Gangsters drove into the area of the OAs” — the Orchestra Albany gang — “to seek revenge for the murder of Ruben Gonzalez. A chance meeting instead took place with members of the Latin Kings who just happened to be driving through this neighborhood.”

The improbabilities — such as the notion that the mysterious Buick could have been used by dueling gangs in back-to-back retaliatory murders — did not deter Guevara or Halvorsen. They homed in on the dark Buick, and that is how Kool-Aid, new owner of one such car, found himself sitting, confused, in the Area 5 interrogation room.

“HE KNEW SOMETHING I DIDN’T KNOW”

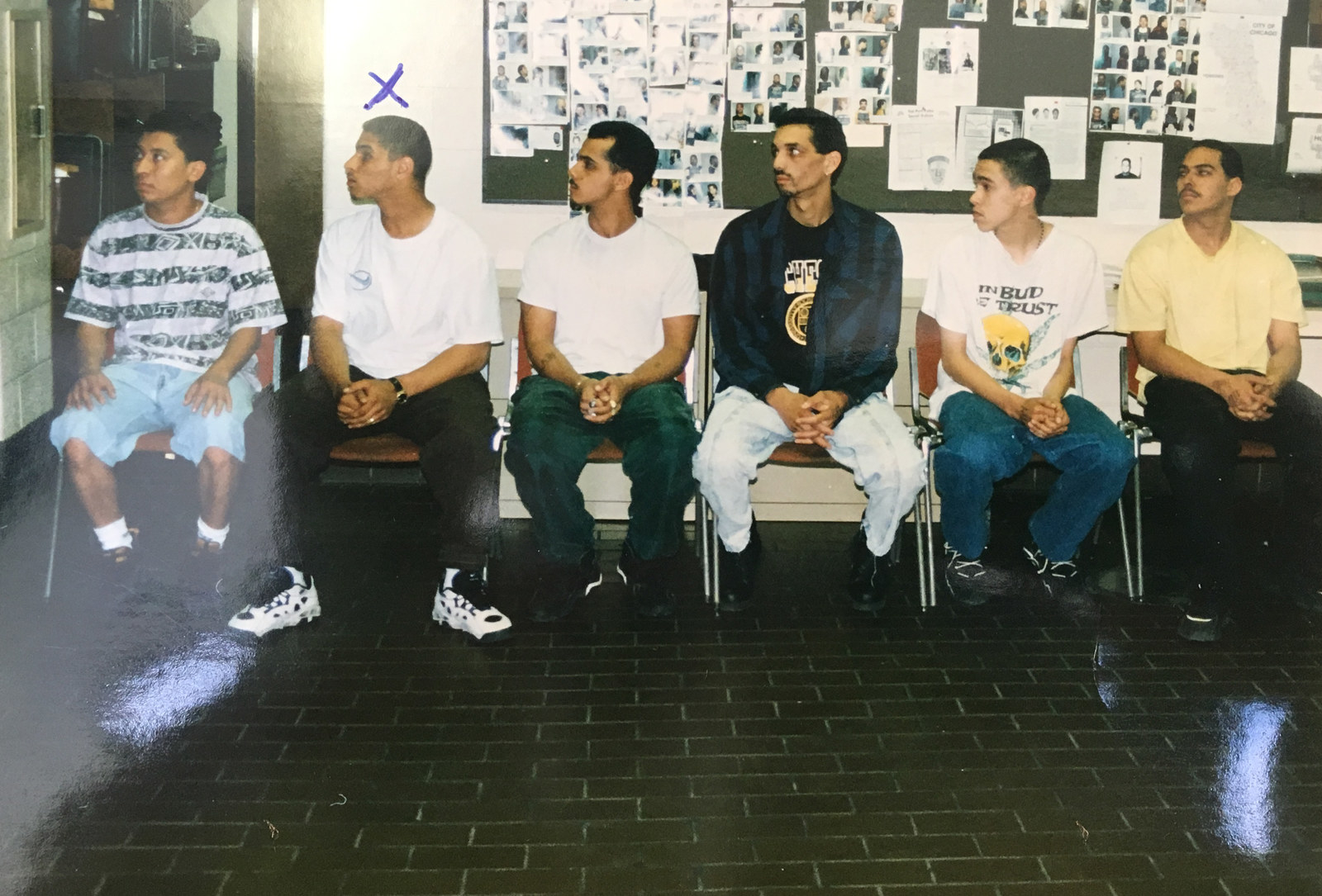

As Kool-Aid waited, Guevara rounded up Macho and Rodriguez, the two survivors of the Logan Square shooting.

Macho and Rodriguez were still reeling from the death of their friend, and hell-bent on justice for him, when they said Guevara pursued a strategy not found in any police manual: He brought them to the station house’s parking lot and told them the car used in their friend’s murder was there. Then he asked Rodriguez to point it out. Macho said Guevara went even further: The detective walked him directly to Kool-Aid’s Buick.

Nancy Franklin, a forensics expert who reviewed the case for Sierra’s legal team, warned that Guevara’s car identification methods “raise concerns” and that informing the witness that the car is there on the lot rather than asking him more neutrally if he sees it “increases the risk of a false ID.”

Guevara watched as Rodriguez came upon Kool-Aid’s black Buick Park Avenue. It resembled the car from the shooting, Rodriguez told Guevara, but it wasn’t a match.

Macho and Rodriguez were still reeling from the death of their friend, and hell-bent on justice for him.

“It don’t have any tinted windows,” Rodriguez later testified he told the detective.

“This is the car,” Rodriguez remembered Guevara saying.

Macho, too, noted the windows weren’t tinted, and that the car didn’t have the custom rims he’d seen that night. “This isn’t the car,” Macho testified he told Guevara.

Yet Guevara and Halvorsen wrote that Rodriguez and Macho “both identified the Black Buick Park Avenue.”

There’s no record showing Guevara or Halvorsen ordered any forensic tests on the car. There was no gunshot residue testing or fingerprinting, basic steps that would have helped bolster their case — or blown up their theories.

Their latest theory — and their final one, as it turned out — was that Thomas Sierra, a 19-year-old who had never before had serious trouble with the law, was responsible for the Logan Square killing. Sierra popped on their radar, they said, because he was friends with Hector Montanez. Montanez previously owned Kool-Aid's Buick, the very Buick that Macho and Rodriguez had testified they had told the detective was not the one they had seen at the Logan Square murder.

When it came time to show Macho a photo array of possible suspects, Guevara allegedly did something similar to what he is said to have done in the parking lot.

Macho testified the detective spread photos across his desk, except for one: Sierra's. That photo he displayed in his hand.

Macho testified that he warned the detective that he couldn’t be sure he could identify anyone because “I was more just looking at his hands.”

But Guevara held on to Sierra’s photo, Macho testified, and seemed like “he knew something I didn’t know.” So despite his own uncertainty, Macho testified, he picked Sierra’s photo.

Armed with that identification, Guevara went to Sierra and asked for a favor, according to Sierra. Would he mind filling in on a lineup?

"You have nothing to worry about," Sierra said the detective told him.

But in little time, Rodriguez picked Sierra out as the shooter in Logan Square.

THE PROSECUTOR SIGNS OFF

When Area 5 police officers felt they had enough evidence to make a case, the first hurdle they had to clear was convincing a lawyer sent by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, whose job was to review police files and determine if a case merited prosecution.

The inglorious work of trudging to dim police stations in the middle of the night often to fell to lawyers in the early stages of their careers and eager to climb the ranks. Officially, the members of the Cook County Felony Review Unit worked 12-hour shifts, answering calls from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. or 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. But it wasn't unusual for these ambitious young assistant state's attorneys to offer to work two or three shifts in a row.

These often sleep-deprived civil servants are supposed to play the skeptic, making sure that every case has sufficient evidence, and that the evidence was lawfully obtained. If the case doesn’t hold up, prosecutors are not supposed to file charges.

If the case doesn’t hold up, prosecutors are not supposed to file charges.

A young attorney named William Farrell arrived at Area 5 to review the Logan Square murder case. Farrell was two years out of the University of Notre Dame Law School, where he had served as articles editor for the school’s law and ethics journal.

Farrell and Guevara sat down with Montanez, the reported gang member who owned Kool-Aid's Buick at the time of the Logan Square murder.

Though both Macho and Rodriguez testified that they had ruled out that Buick and said it wasn't used in the crime, Montanez —in the room with Farrell and Guevara — was told that his Buick had been identified as the murder vehicle and that he and Sierra were now suspects in the Logan Square murder.

Faced with this new information, Montanez confessed to being there, but said he had not been the shooter.

According to Guevara's police report, Montanez said that he and Sierra were cruising around Logan Square, smoking and drinking, when Sierra reached under his seat, pulled out a gun, and started firing.

Montanez said a third man had also been in the car, but Montanez said he “didn’t want to get him involved” and declined to give his name.

Neither the prosecutor nor the detective pressed Montanez to identify this person, according to police files, despite the fact that the third person would be both an accomplice and a key witness.

Guevara and Halvorsen's report claimed that Farrell said there wasn't enough evidence to charge Montanez or the mystery third passenger. Yet defense attorneys contacted by BuzzFeed News said that the getaway driver in a murder case (the “wheelman,” in criminal court slang) would almost always be charged for his role in the case. But Montanez walked free. He never even testified at Sierra's trial. Prosecutors never called him.

Why not? What was the reason for such soft treatment of a known gang member who was part of a murder? And why didn't he tell his story in open court?

No one will say. Farrell did not respond to requests for comment. Montanez did not respond to multiple requests for comment from BuzzFeed News, including letters, phone messages, text messages, and in-person visits to his home.

Sierra, however, was on the hook for murder. Farrell filed the charges.

A REMARKABLE DEVELOPMENT (PART 2)

As May 30 faded into the 31st, Guevara and Halvorsen still had nothing to go on for the Gonzalez murder on Fullerton Avenue. Shortly after daybreak, police let Kool-Aid go home.

For the next week, the Fullerton Avenue case seemed to go cold. No updates in the file. No notes from any interviews.

Until Guevara claimed to have received a call that would break the case wide open.

The unexpected call from an outsider, offering the key to solving a murder, is a phenomenon that occurs with striking frequency in the 51 cases in which Guevara is accused of misconduct.

In this instance, Guevara said the crucial phone call came from the victim’s mother, Esther Reyes. The detective claimed that she called him to say that Jorge Mulero, a close friend of her late son, had seen Kool-Aid commit the murder. Neither Reyes nor Mulero could be reached for comment.

Mulero was out on parole at the time. In police reports, he said that about an hour before the murder, he and the victim, Gonzalez, ate at a diner and then ran into Kool-Aid, who threatened Gonzalez over $500 in stolen tires.

The argument escalated and Kool-Aid jumped in the dark gray Oldsmobile, ramming Gonzalez and Mulero in their Pontiac as he fired his gun, Guevara and Halvorsen's new police report said. The force of Kool-Aid’s car caused Gonzalez to lose control of his Pontiac, spinning into a light pole.

In Mulero’s telling, according to the police reports, as Gonzalez opened the car door and tried to run, he fell to the ground. Kool-Aid stood over him and fired the fatal bullets. Terrified, Mulero fled on foot.

So much for Guevara and Halvorsen's initial theory about dark Buick being involved in this murder. Or for their theory about the Orchestra Albany gang being responsible for the killing. So much for the lead about the silver car that Malczyk had seen at the crime. So much for any of the other witnesses the first detectives on scene had found, who in separate interviews gave accounts at odds with this one.

Kool-Aid was at home, watching TV when detectives showed up on June 8, 1995, slapped handcuffs around his wrists, and told him he was charged with committing the Fullerton Avenue murder of Ruben Gonzalez.

THE SERGEANT SIGNS OFF

Guevara and Halvorsen filed their police report in the Gonzalez murder and left it for the supervising sergeant’s review.

Along with felony review attorneys, the sergeant’s evaluation is a critical step in the policing process, a way to make sure officers conduct their investigations properly and make solid cases — one of the first lines of defense against police misconduct.

Edward Mingey, a tall, sturdy man, was the sergeant who picked up Guevara and Halvorsen’s report on the Gonzalez murder. Like Guevara, Mingey was a product of the city’s Northwest Side. He was a cop’s cop. Mingey had helped Guevara out with loans, in violation of police policy. And he had signed off on reports in at least five of the 12 cases that Guevara and Halvorsen worked that were later overturned.

In 1984, Mingey — who did not respond to questions for this story — looked on as Guevara broke the arm of a teenage girl who had been folding laundry when officers barged in looking for her older brother, according to a federal lawsuit filed by the girl’s family. The suit was dismissed on a technicality.

And it was Mingey who described the purported eyewitness to a 1993 murder as “the best witness I ever talked to.” He added, “I never talked to anyone who gave me more info and it turned out to be totally legit,” despite the fact that investigators would later determine the man almost certainly could not have seen what he claimed to have witnessed. The two men convicted in that case served 23 years and were released in 2016 after an appellate court found “profoundly alarming acts of misconduct in the underlying investigation.”

Now Mingey had the Gonzalez report in front of him, and it contained glaring improbabilities.

Mulero said he was riding shotgun in the car that night, despite the cop on the scene, Malczyk, saying the passenger seat was empty.

He said he had just eaten with Gonzalez despite autopsy results that showed Gonzalez’s stomach was empty.

He said that Kool-Aid fired the fatal bullet after the car accident, as Gonzalez lay partially in the street, despite a bullet hole in the driver’s headrest and shell casings found a block away from the accident scene.

Malczyk hadn’t picked anyone out of a lineup. No one had gone back to the man who lived above the shell casings.

Yet Mingey, an officer with 29 years of experience, approved the report.

Guevara and Halvorsen had closed two murder cases. If anyone within the justice system was worried about holes in the evidence, or the failures of basic police procedure, not a word of their concern was documented. If anyone in the system was worried that people were being railroaded, it never made its way into any official report.

A SURPRISE FROM THE WITNESS STAND

In February 1997, Thomas Sierra went on trial for first-degree murder in the Logan Square killing.

Prosecutors based their case on the testimony they expected from the two people who had been in the car with the victim, Macho and Rodriguez. There was no other evidence offered in the case. No forensics. No other descriptions of the car. No motive. No accomplices.

Rodriguez took the stand and testified as prosecutors had expected. He pointed to Sierra.

But when it was his turn on the stand, Macho stunned the courtroom.

When it was his turn on the stand, Macho stunned the courtroom.

“Do you see the person present in court today that you saw shoot at you and your car and your friend Noel Andujar?” the prosecutor asked.

Sierra sat less than 30 feet away.

“No, I don’t, ma’am,” Macho responded.

The prosecutor, Patti Sudendorf, tried to regain control of her witness. Then what about the picture you previously selected, she asked.

“I pointed to a picture he told me to pick out,” Macho testified.

He explained that Guevara had laid out a series of photos in front of him but kept Sierra’s in hand.

“I was mad, I was angry,” Macho explained. “My friend got shot and he told me to pick him out because he” — Guevara — “had reason to believe this was the guy.”

But what about the dark Buick Park Avenue, the one Macho had picked out of the Area 5 car lot, the prosecutor pressed?

“I told them that wasn’t the car,” Macho insisted. The windows weren’t tinted and the rims didn’t match. The wheels were factory-issued, not custom.

With testimony that the lineups were tainted and with no other evidence connecting Sierra to the crime — and the prosecution never calling to the stand Hector Montanez, Sierra’s friend who gave the damning statement naming Sierra as the shooter — his public defenders didn’t call a single witness.

If they were gambling that their case was made, they bet wrong. A jury took little time declaring Sierra guilty.

In a separate trial, prosecutors forged ahead in trying Kool-Aid for the murder on Fullerton Avenue that killed Gonzalez.

Kool-Aid, who said he was stabbed while in jail awaiting trial, took a loan from family members to hire the best defense attorney he could afford. He was acquitted.

FREEDOM BUT NO VINDICATION

Last month Sierra walked out of prison having completed his sentence. Despite his release, he is still trying to prove that he was framed; his attempts to vindicate himself, still pending, have outlasted his prison term. “I ask myself every day why he picked me,” Sierra said.

It’s a question Guevara may never answer: The detective has refused to talk about how he did his job, even to prosecutors trying to defend his work.

Meanwhile, Kool-Aid, now 49, has held a job as a track maintenance worker for the Chicago Transit Authority for nearly three decades. He catches glimpses of Guevara on the local evening news.

Not long after his acquittal, police summoned Kool-Aid to the parking lot where they held cars as evidence. Officials handed him back the keys to the dark Buick Park Avenue, short body, without the custom wheels, without the tinted windows.

He opened the car and was overcome by a stench. A cat had snuck into the trunk of the car during the time he was in jail and had given birth to a litter of kittens, who’d died there.

“I definitely didn’t want that car no more,” he said. ●