ODANAH, Wisconsin — Hours after seeing her 14-year-old grandson, Jason, lying in the street just feet from her home, with police and EMS hovering over his motionless body, Cheryl Pero found herself in the cavernous gymnasium of the Bad River Reservation community center.

Cheryl and her husband, Al, couldn’t go home — where they’d raised Jason since infancy — because it was a crime scene.

So the family awaited word in the local gym about why an Ashland County Sheriff’s deputy had just fired two shots into the chest of Jason, who friends and family say was a relatively normal, happy child. With news of the shooting spreading rapidly via text message and Facebook, members of their tight-knit tribal community soon joined them.

Tracy Bigboy, a neighbor and victim services coordinator for the tribal government, was dispatched to take care of the Peros’ needs. She stood in the cold air outside of the community center, quietly smoking a cigarette, until Ashland County Sheriff Mick Brennan pulled off Highway 2 and into the parking lot.

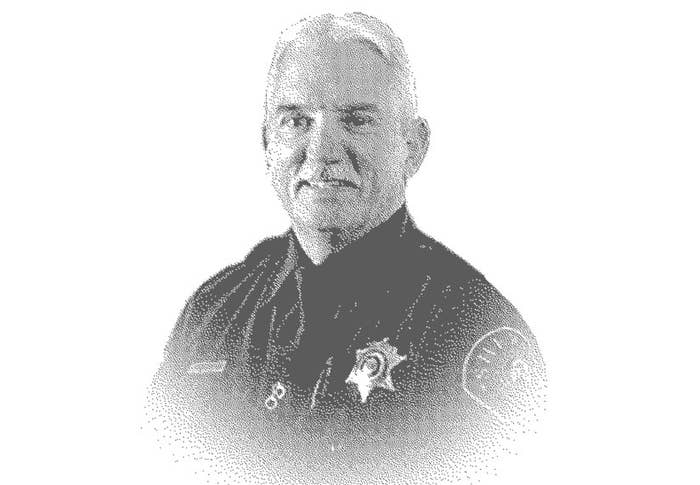

With his squared-off shoulders, neatly cropped silver hair, and mustache, the 62-year-old Brennan has a carefully crafted by-the-book reputation and looks every inch the small-town sheriff. As he and one of his investigators approached, Bigboy stopped them, warning the sheriff that emotions were running high inside the gym and urging him to talk to the family privately.

As the Peros huddled in private with Brennan, it seemed to the family that the sheriff hadn’t come with answers, or even condolences. His main message, as the grieving Peros remember it: Let him control the public narrative of Jason’s death.

“Don't talk to the media,” Bigboy and the Peros remember Brennan telling them. “Let us go first so we can tell you what to say.” And they say he had a warning for the community: Settle down and don’t riot.

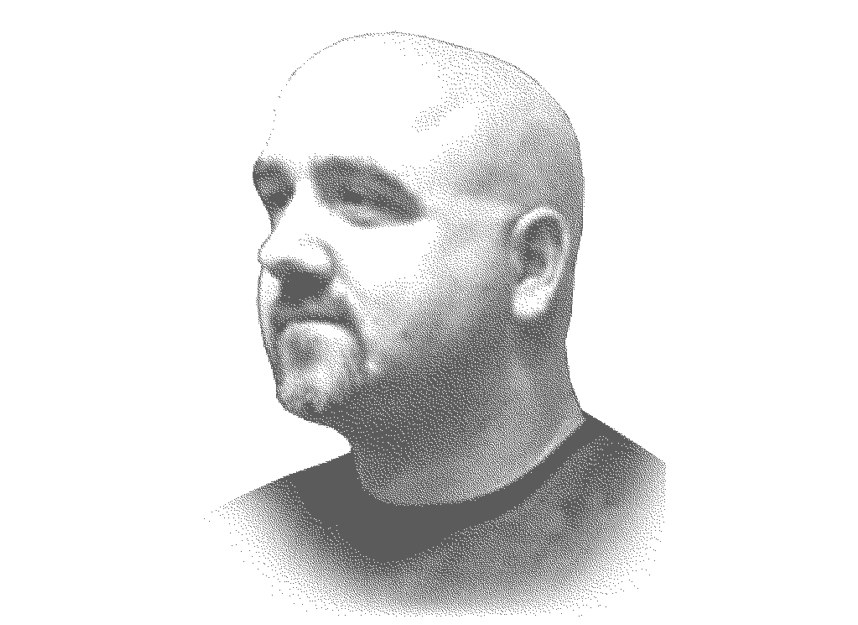

Now, two months after Jason took two bullets to the chest on Nov. 8, his family still doesn’t know exactly what happened the morning that Deputy Brock Mrdjenovich shot him dead. Jason’s family says the sheriff has told them nothing, and Brennan did not respond to multiple requests to speak to BuzzFeed News about the shooting and about local law enforcement’s relationship with the Bad River community. Michael Nieskes, the St. Croix County District Attorney who has been appointed as a special prosecutor to investigate the case, declined to comment.

The feeling of sadness and loss is palpable among members of the Bad River Band. But there’s also a deep sense of numbness and fatalism here that manifests in the nonchalant ways people talk about other violent encounters involving law enforcement and Native Americans. Jason’s death was at least the second time in as many months that a member of the Bad River Reservation had been killed by uniformed officers: On Oct. 28, a Jackson County Sheriff’s deputy shot and killed 27-year-old Lucas DeFord in nearby Black River Falls.

“This has been going on for generations and generations, and it’s not going to stop.”

Locals have long complained about being pulled over for what they consider no good reason. “Driving while Indian,” they call it. And then there’s “the women,” a sort of shorthand that refers to allegations detailed in federal lawsuits that Sheriff Brennan did nothing as one of his jailers repeatedly raped and assaulted Native American women. “You’ve heard about the women, right?” locals say almost between thoughts.

The lack of information since Jason’s shooting has only compounded tensions here, laying bare the deep-rooted, systemic racial divisions between the Bad River tribe and the white community of Ashland.

“This has been going on for generations and generations, and it’s not going to stop,” Bigboy said.

In April 2013, a Native American woman with the initials J.L. arrived in the Ashland County Jail.

It didn’t take long for J.L., then in her early twenties, to catch the eye of Ashland County correctional officer Christopher J. Bond. The women’s showers, with their waist-high walls and central location in the jail, gave Bond — and anybody else who happened to walk by — a perfect view to ogle female inmates as they bathed.

According to a federal lawsuit filed in March by J.L., Bond would leeringly comment on her “pretty mouth” and simulate ejaculating into it when she ate jail-issued meals of hot dogs or kielbasa. He’d regularly corner her in areas of the county jail without cameras, forcing her to open her jumpsuit so he could grope her, said the lawsuit, one of five filed since January 2017 against the county and sheriff’s department alleging violation of the women’s civil rights. On nights he was on watch, Bond would direct J.L. to lie naked on her bed and masturbate while he watched on the jail’s surveillance cameras, the 25-year-old woman alleges.

On Nov. 2, 2013, Bond was designated by prison officials to drive J.L. 70 miles west to St. Luke’s hospital in Duluth, Minnesota, for an emergency medical procedure to remove an abscess from one of her breasts.

J.L. was loaded into the back of a sheriff’s cruiser outside the jail, the lawsuit alleges, but once outside the county line, Bond pulled the car over, unshackled the prisoner, and ordered her to sit in the front seat beside him and unbutton her jumpsuit. Then, as he drove down the highway, Bond groped and fondled J.L., according to the lawsuit. Thirty minutes later, he pulled into a rest stop and ordered J.L. to follow him into the men’s bathroom, where he allegedly raped her. Afterward, J.L. said, he used water and paper towels to erase evidence and avoid arousing suspicion from medical staff at St. Luke’s.

According to court filings, at least four other women — all of whom are Native American — were also repeatedly assaulted or raped.

Even after she was released, J.L. said, Bond continued to torment her. In September 2015, while she was still on parole and seven months pregnant, Bond forced her to have sex with him in his pickup truck, her lawsuit says. J.L. said she had no choice but to go along — Bond, after all, was a correctional officer and worked for the sheriff. Plus, her parole officer was Bond’s girlfriend at the time, the lawsuit says, and J.L. worried she’d be sent back to jail.

J.L. wasn’t Bond’s only alleged victim. According to court filings, at least four other women — all of whom are Native American — were also repeatedly assaulted or raped by Bond between 2013 and August of last year.

Bond’s alleged reign of terror over women in the Ashland County Jail would only come to an end on Aug. 24, 2016, when another correctional officer caught him and a prisoner leaving a closet where he’d allegedly forced the woman to perform oral sex. Later that day, Bond killed himself. According to a source familiar with the case, Bond shot himself in the head.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Native Americans are more likely to be killed during an interaction with law enforcement than any other racial group. In 2017 at least 31 indigenous people died as a result of an encounter with law enforcement. In 2016, the number was 29.

On a per-capita basis, Native Americans are 12% more likely to be killed by law enforcement officers than black Americans — and three times more likely than white Americans.

If you live on one of the dozens of reservations across the country in which local, white police forces from nearby border towns have jurisdiction, the chances that you’ll end up in jail are high. In Ashland County, for instance, Native Americans make up 11% of the population but account for 44% of the inmates in the county jail, according to data collected by the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit criminal justice research and reform group.

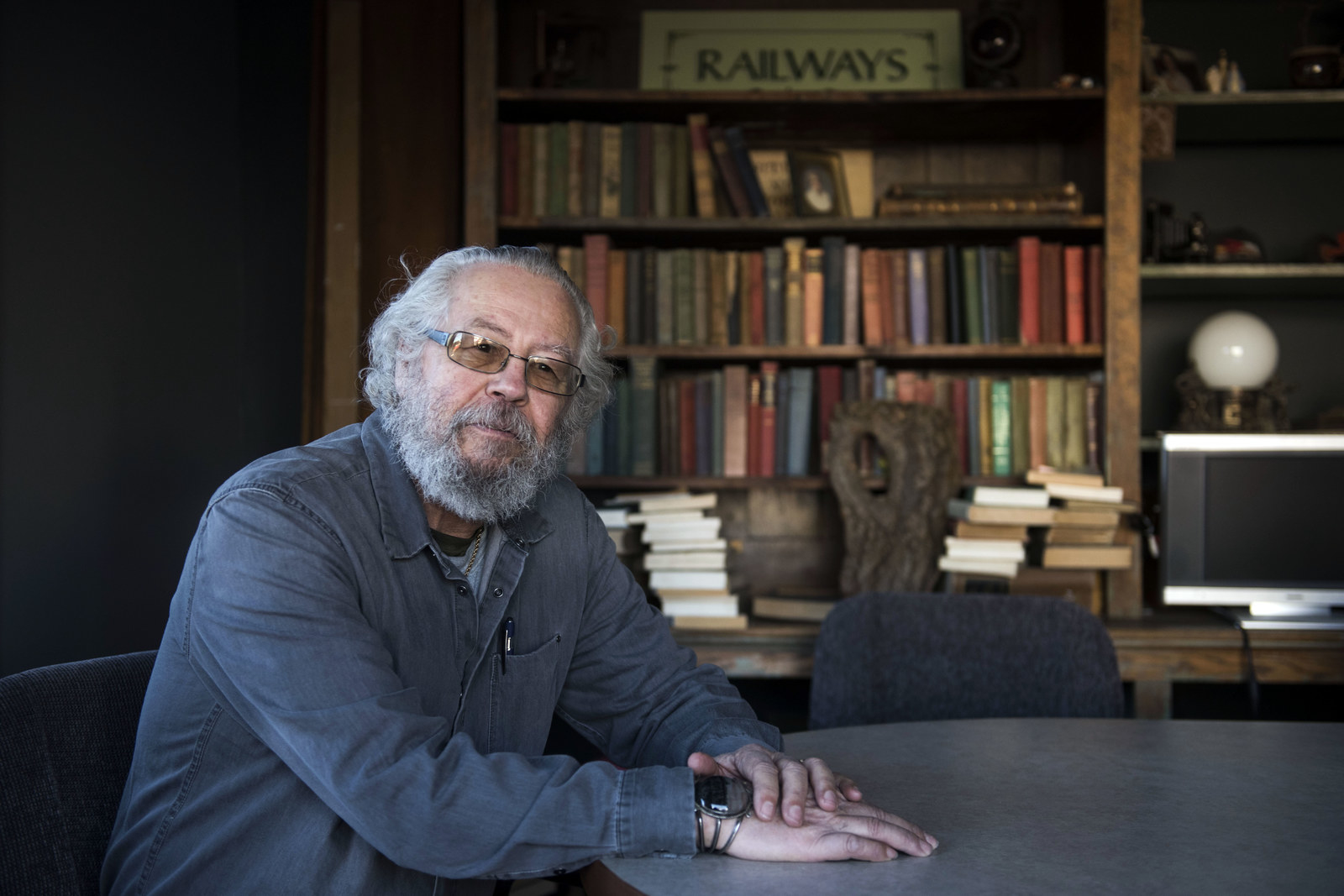

For tribal leaders here and across the country, that leads to one conclusion. “That becomes a disproportionality that speaks to some sort of institutionalized injustice going on,” says Bad River Tribal Chairman Mike Wiggins.

To understand the complex relationship between indigenous Americans and border town police means understanding that in these communities, history is in the present tense.

For most Americans, Native Americans are little more than a footnote in the history books, bit players in the founding and expansion of the United States. But in hundreds of communities like Ashland, 235 years of colonization, forced relocation and assimilation, and racism is very much a reality.

Established as part of an 1854 treaty with the broader Ojibwe nation, the Bad River Band’s sprawling reservation is home to more than 1,300 members, according to US Census data. Like many reservations, Bad River is relatively poor: Census data shows more than 9% of the population is unemployed, and 20.1% of families live below the poverty line.

You don’t have to look far back for examples of racial tensions boiling over here. During the Wisconsin Walleye War between 1988 and 1991, white protesters hurled racial epithets and sometimes eggs and rocks at Ojibwe tribal members spear fishing for walleye, a tradition protected under treaties between the US government and the tribe. Although the violence eventually ended after a federal judge upheld the Ojibwe right to spear fish, distrust and bitterness between the two communities remained.

“As much as you do as a parent bringing in a new generation to try and break those cycles, it’s never going to be broken.”

Native Americans say the discrimination they face is not only systemic, but largely accepted, and it’s gotten worse under President Donald Trump. Trump has derisively referred to Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren as Pocahontas because of Warren’s claim to have Native American heritage. In November, Trump hosted Native American Code Talkers at a White House event that prominently featured a portrait of President Andrew Jackson — who committed acts of genocide against Native Americans. Trump’s approval of the Keystone XL pipeline, modifications to the Bears Ear National Monument in Utah, and other projects impacting Indian Country have also angered many Native Americans. “The sad thing about it is that the majority of our country thinks just like that,” Bigboy said, a few hours after the Code Talkers event at the White House. “As much as you do as a parent bringing in a new generation to try and break those cycles, it’s never going to be broken. Because this is a white predominant area that we live in.”

For all the distance between the two sides, however, they are inextricably linked, and in places like Ashland County, white residents and Native Americans coexist in an uneasy truce of convenience and routine. The reservation’s small casino is a significant economic driver, particularly during the summer tourism season. Each day, hundreds of tribal members commute into Ashland for work, and their children attend Ashland’s public schools.

Under federal law, the Ashland County Sheriff’s Department is one of dozens of local law enforcement agencies across the country with authority over neighboring reservations. Known as Public Law 280, in practice, the 1953 law has resulted in largely white forces with little understanding of Native American communities policing them.

Things are better than they used to be, said Wiggins. “In the ’70s and early ’80s, that was light years worse than it is today,” he said, adding that back in the ’80s, during hunting season, one sheriff’s deputy was notorious for using routine traffic stops to confiscate Native Americans’ rifles — which he used to stock his black market rifle business.

“It’s indoctrinated into us … that you don’t want to call the police, because they’re not to be trusted.”

The problems with law enforcement extend to those parts of Indian Country where the Bureau of Indian Affairs — the federal agency responsible for overseeing much of Indian territory — remains the primary law enforcement agency. Ruth Hopkins, a Lakota Indian and former tribal judge for the Spirit Lake Nation in North Dakota, said she was repeatedly frustrated by the bureau’s responses to crimes reported on the reservation. Hopkins recalled a 2016 case in which a Spirit Lake woman reported being raped by a nontribal member. The case was referred to the BIA for prosecution, but when tribal leaders tried to determine if a criminal case was being pursued, Hopkins said they were stonewalled.

The result is that few Native Americans trust law enforcement.

“As somebody born and raised on the reservation, it’s indoctrinated into us … that you don’t want to call the police, because they’re not to be trusted,” Hopkins said.

To a large degree, law enforcement attitudes toward Native Americans are simply a reflection of how the broader white community sees them. Particularly in border towns like Ashland, pressed uncomfortably close to reservations, stereotypes of the “drunken, lazy Indian” have calcified into truths for many whites. In many ways, the racial divide in border towns is as much muscle memory as anything else. “For the people who grew up in these border towns, it’s what they were taught,” said John Dossett, general counsel for the National Congress of American Indians.

“That’s what border towns do,” said Ashland City Councilman Richard Ketring. “You get this cancerous atmosphere that is really hard to eradicate.”

In the local gym that November day, after their meeting with Sheriff Brennan, the Pero family was stunned.

Jason’s parents pressed the sheriff for answers but were met with curt replies, they said. The angrier and more frustrated the family got, they say the shorter Brennan became with them. At one point, the Peros said, Jason’s mother, Holly, confronted Brennan, demanding he answer for his deputy’s actions.

Brennan, clearly annoyed, interrupted the grieving mother.

“Wait until the evidence comes out,” Jason’s grandparents recall the sheriff saying.

That came in the form of a press release from the state’s Department of Justice three days later. The release implied Jason may have intentionally provoked the officer into shooting him, citing unspecified evidence seized from Jason’s bedroom and “initial reports” indicating he had been despondent and that he’d called 911 to describe a man with a knife — a description the sheriff’s office said fit Jason himself. The release said Jason lunged at the deputy with a knife and ignored multiple commands to drop the weapon.

“Bullshit,” Jason’s grandmother Cheryl Pero said flatly.

The release described Jason as 5 feet 9 inches and 300 pounds; his family and friends say he was 5 feet 3 inches and weighed significantly less than 300 pounds. No other information has been provided. The Ashland Sheriff’s Department has repeatedly refused to comment and hasn’t released any official documents related to the case, including the transcript or audio of the 911 call, the official police report, or the autopsy report.

The press release came as the family was burying the 14-year-old, and by nightfall, the narrative the family says Brennan had crafted had taken hold. While, initially, local media outlets had emphasized Jason’s age and his family’s demand for justice, a new storyline had appeared, one that painted Jason as the aggressor who’d brought the shooting on himself.

“Our children represent the survival of our tribe, of our nation moving forward.”

“What hurts us the most is lots of people saying things about Jason that wasn’t true. That he was this monster, he was this 5-foot-9 man. He was a kid!” his friend Vinnie Bender said.

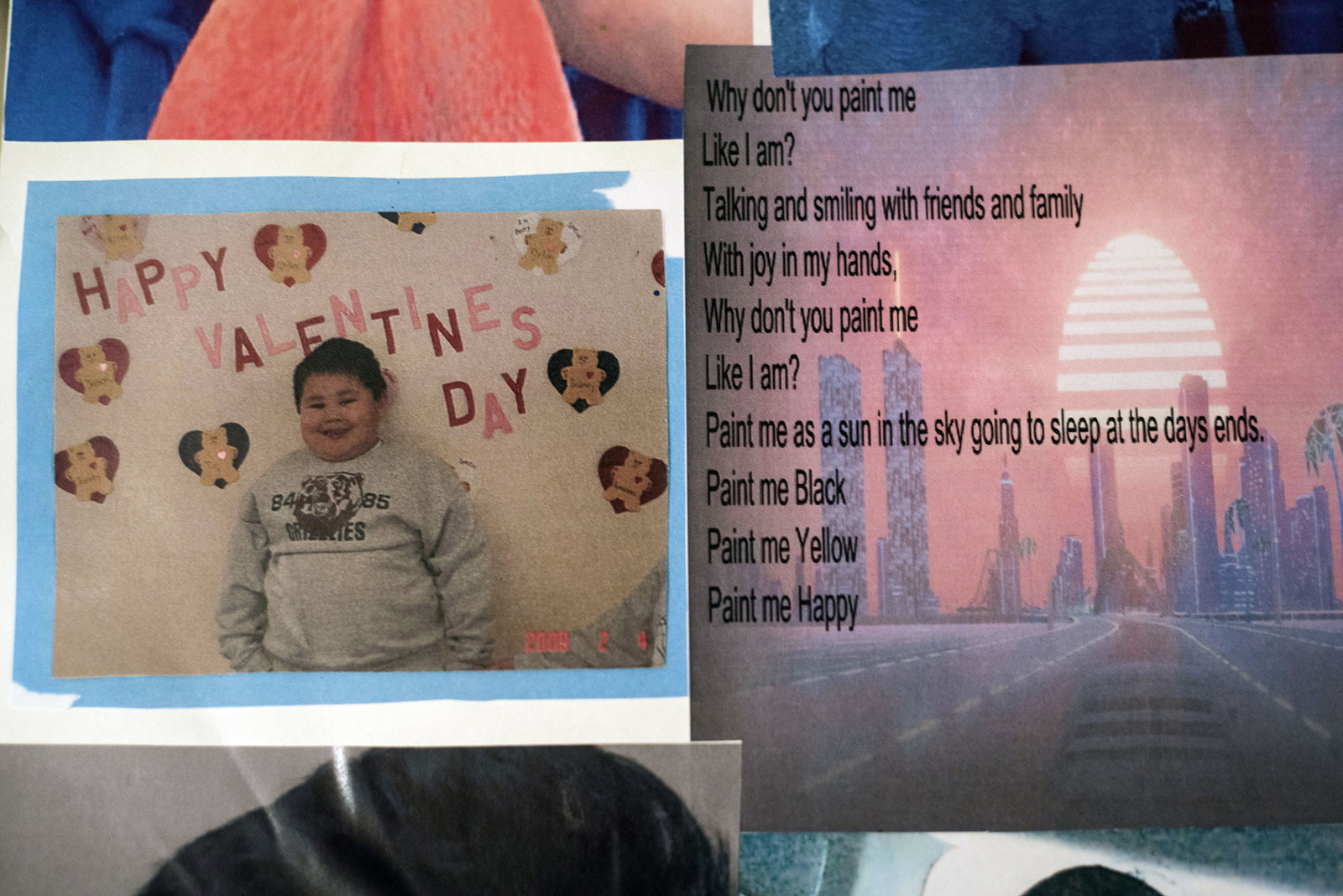

Despite his youth, Jason held a prominent place in his community, in part because of his interest in traditional Ojibwe culture. He played in a tribal drum group, studied the Ojibwe language, and was part of a group of young tribal members committed to preserving the tribe’s culture. “Our children represent the survival of our tribe, of our nation moving forward. Jason was one of many that we consider a national treasure here in Bad River. His loss is devastating,” said Chairman Wiggins.

Vinnie and Lilly Wiggins, Jason’s two best friends, insist that he was a stabilizing force in many of his peers’ lives, not the despondent young man the sheriff’s department described.

“I struggle a lot with depression. And he helped me with that a lot. Just like the way he’d talk to me, and he’d call me in the middle of the night to make sure I was OK. He was that type of person,” Lilly said.

Vinnie dismissed questions about Jason’s Facebook page, where he would occasionally post dark memes, like one with a boy holding a gun to his head saying “I make everything weird, I hate myself,” that could suggest an unhappy side. “They’re memes, little jokes that adults don’t get. Just kid jokes,” Vinnie said.

And even if Jason was depressed, one of the nagging questions for Bad River residents is what happened in the eight minutes between the 911 call, at 11:40 a.m., and the moment Mrdjenovich shot Jason at 11:48 a.m. If Mrdjenovich had tried to de-escalate the situation, for instance by calling for backup or trying to reason with Jason, Wiggins said far more time should have elapsed before the deputy opened fire. But the press release gave no details of what occurred once Mrdjenovich got the call.

“There was too much that was missing,” said Wiggins, who before entering politics worked as a firearms instructor for the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission. Among other things, he trained conservation officers in the use of deadly force, de-escalation, and other tactics.

Wiggins has written to the US Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division to request a formal investigation into Jason’s death, charging that Mrdjenovich “inflicted injury without knowing the circumstances of the situation.”

The DOJ has not yet responded to Wiggins’ request. A DOJ spokesperson declined to comment on the issue.

For Jake Deragon, a father of five and neighbor of the Peros, Brennan’s handling of the case hits particularly hard. “He was my first sergeant when I was in the military, so I actually trained with him. We trained under the NATO rules of war, ya know? We don’t shoot civilians, we don’t shoot women and children, we don’t target them,” Deragon said. “He’s not the man I once knew. I’m ashamed that I once shed blood, sweat, and tears with that man. Because I was willing to lay down my life for him.”

“Poor Jason was gunned down like cattle,” he said acidly.

Nobody knows when the sexual assaults in the Ashland County Jail started. After all, female tribal members told me this sort of behavior is so common, so normal, it’s become hardly worth mentioning.

“We’re Indian women. We don’t have a voice,” said Sandy Gokee, a cousin of Jason’s. “Who’s going to believe us?”

In the months following Bond’s death, J.L. and the four other women filed federal lawsuits against the county, Sheriff Brennan, and Ashland County Jail Administrator Anthony Jones.

In their complaints, a disturbing picture emerged of Bond targeting Native American women in their twenties and early thirties, often while other correctional officers were aware of his actions. All five complained of being forced to shower in plain sight of male and female guards and inmates, and of Bond making lewd comments and of using blind spots in the jail’s surveillance system to assault them. For instance, the complaints say that Bond would routinely take the women into the jail’s booking area ostensibly to arrange for bail. In the booking area, out of sight of jail cameras, he’d assault them, the suits allege.

“We’re Indian women. We don’t have a voice.”

According to the complaints, while Bond tried to hide his behavior, there is video evidence of assaults, including footage of Bond leading the women into parts of the jail not covered by cameras on multiple occasions. In at least one case, court documents say, video shows Bond reaching through the bars of one woman’s cell and fondling her — video allegedly viewed by Brennan after he became aware of Bond’s suspicious activity.

In addition, the complaints allege at least one other correctional officer witnessed Bond leading a woman out of the library closet, where the woman says in her lawsuit that she was forced to perform oral sex on Bond. That woman’s cellmate also heard Bond ordering her to expose her breasts to him, the suits say.

Two of the women — J.L. and a woman identified in court documents as B.L.W. — allege that when Brennan became aware of Bond’s behavior, rather than suspend or investigate him, he pressed the city’s police department to investigate the women for prostitution. Police Chief James Gregoire told the Ashland Daily Press the investigations had been asked for by the county district attorney “to make sure that the inmates were not providing sexual favors for something, like extra meals or in and out early, or talk to a defense attorney, or whatever.”

Neither Brennan nor Jones responded to requests for comment on the lawsuits. Both remain on the job. The state’s Department of Corrections is looking into the allegations, but it’s unclear if the sheriff’s department has launched its own internal investigation.

According to one source familiar with the jail, a blanket now partially obscures the view of the women’s shower from a jailer observation station.

The sheriff’s department has hired one of the state’s top law firms, Axley, to represent it in the case. Although the trial isn’t expected to begin for several months, defense attorney Lori Lubinsky has filed court documents that include statements from the women acknowledging they did not report Bond to Brennan or other jail officials, potentially setting up a defense based on the argument that the department had no way of knowing about Bond’s behavior.

Lubinsky declined to comment.

In the wake of Jason’s death, the tribal council is beginning a review of its relationship with the sheriff’s office. The situation is made particularly difficult because, like much of the country, Bad River has been hit hard by the opioid crisis. Without the money to pay for its own police force, the tribe relies on the county.

“It’s gotta be a part of the norm, and part of the way the Ashland County Sheriff’s Department approaches our tribe.”

One solution could be a shift to a community policing model by the Ashland County Sheriff’s Department. In the 1990s, there were several officers who worked on the reservation who, by becoming an active part of the community, built trust and respect among the residents. But those officers have since retired, and efforts by law enforcement to build trust since then have been few and far between, reservation residents said.

“It’s gotta be a part of the norm, and part of the way the Ashland County Sheriff’s Department approaches our tribe. It’s getting out of the car and walking into the gym at night and talking to kids, and stuff like that,” Wiggins said.

Of course, that will require communication between the tribe and the sheriff’s office. So far, neither the state nor Brennan’s office have provided any further information on the shooting. During a community meeting on the reservation in late December, it was announced that Mrdjenovich had returned to work after a month of paid suspension.

At the request of the tribe, Brennan did not attend the meeting.

The impact of Jason Pero’s death has rippled throughout both the Bad River and Ashland communities.

Some of the effects have been relatively mundane. Wiggins says, for instance, that while white hunters normally flock to the reservation during deer season, this year they were notably absent. Wiggins speculated the drop may be because some whites worry about reprisals for Jason’s death.

Others have been more pronounced. “I don’t see no kids playing outside like they used to. There were always kids playing outside. All over Odanah. Since the shootings you don’t see kids playing outside,” said Jason’s grandfather, Al.

“This has been going on for 300 years, and this is where we say ‘Enough’s enough.’”

“It scares me. My son’s 6’2”, 350 pounds, and he’s 13 years old. He’s a big man for being 13 years old,” said Deragon. “What scares me is what were the motives behind this cop? What was he looking for, a large Indian person? That fits the bill for a lot of our youth.”

Gokee, who teaches at Ashland’s middle school, was suspended over an angry Facebook post in which she accused Deputy Mrdjenovich of murdering Jason. Ashland School Superintendent Keith Hilts, in his letter notifying Gokee of her suspension with pay, accused her of creating racial tension in the school and making the children of white police officers feel unsafe. Gokee returned to work at the beginning of January.

Gokee said her post was provocative but didn’t threaten Mrdjenovich or other police officers. Instead, she said, it was an expression of her anger and frustration, not just about Jason’s death but about broader systemic problems facing Native Americans. “This is not a new thing. This has been going on for 300 years, and this is where we say ‘Enough’s enough, we can’t take it anymore,’” Gokee said.

Some white students began taunting Jason’s friends, they and teachers familiar with the situation said. “They’d say, ‘Oh, he deserved it. He had a knife,’” said Jason’s friend Vinnie.

Early on the morning of Dec. 2, Jason’s grandparents, Cheryl and Al Pero, once again found themselves in the reservation’s community center. The couple sat quietly by the door to the gym, greeting arriving friends and family with sad smiles.

It would be a difficult day. Ojibwe believe that when someone dies, relatives must not speak their name or look at their picture. To do so can interfere with the journey to the afterlife, keeping their souls connected to this world.

Still, the family understood the importance of the gathering. Jason’s friends had organized a “healing walk” from the reservation to downtown Ashland to honor their friend and, they hoped, to plant the seeds of a new movement, which they’re calling Jason’s Message, to address the conflicts between the two communities.

As volunteers handed out T-shirts and tote bags emblazoned with the Jason’s Message logo — a turtle with two roses atop its shell — that his friends had designed, the gym slowly began to fill with friends and family. Many carried signs with pictures of Jason on them.

Representatives from other Ojibwe bands, the Lakota nation, and other tribes across the country came for the walk, as did Ketring, the city councilman, and a number of other white residents from Ashland. Clyde Bellecourt, an 81-year-old Native American civil rights pioneer, also came, along with a group of volunteers from the American Indian Movement to provide security for the walk. The only condition Jason’s friends had set for the walk was that no Ashland County sheriffs be there.

All told, more than 500 people participated in the 12-mile trek from the Pero home.

Shortly after sunset, the marchers reached downtown Ashland, huddling close to the town’s band shell in the cold December wind.

Jason’s friends took turns reading from a statement the group had written in which the Bad River youth called on their community and the white community of Ashland to come together “in unity and love because that is the message our friend and brother would want us to share … this is not an Indian issue. It is not a white issue. This is a community issue.”

As the students read aloud, much of white Ashland stood just one block over, their backs to the march as they watched the annual Christmas parade go by in the other direction. ●