Standing on the side of South Sasabe Road just outside Three Points, Arizona, Alvaro Enciso and Ron Kovatch consult their handheld GPS. Displaying a two-mile radius, the screen is littered with dozens of red dots. “The dots are deaths,” Kovatch explains.

It’s overcast and not yet 10 a.m., but the temperature has already climbed past 90 degrees. By the time noon rolls around and the clouds high above the desert have burned off, it’ll be 113 degrees, hot enough to burn your lungs with every breath.

Enciso takes in the view and raves about the beauty of the Sonoran Desert, which draws tourists from across the globe. “But this desert has a secret,” he says. “Three thousand people have died here. Two thousand have disappeared. And nobody knows about this shit.”

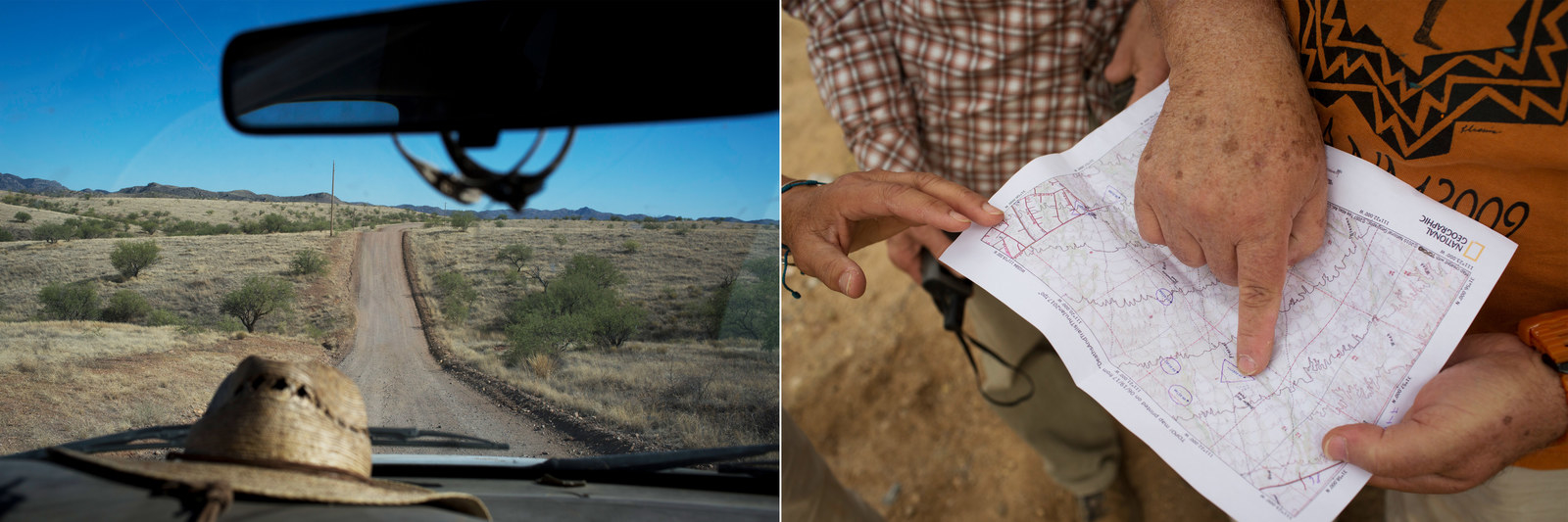

The two men consult Enciso’s map of the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, discussing the route for the day’s journey. The night before, Enciso plotted out three potential stops for the day, areas where activists know migrants crossing the border illegally often walk — and where the remains of fallen immigrants have been found.

It’s a familiar routine for the volunteer members of the Tucson Samaritans, who, since July 1, 2002, have made thousands of near-daily trips into the desert to leave food, water, and other supplies for the immigrants who walk for days through this unforgiving environment. Over the last three years, Enciso has also carried something else on his trips: simple wooden crosses adorned with red dots to mark where an increasing number of migrants have died chasing the American dream.

For Enciso, a well-known artist in Tucson, what’s happening here is personal. “I’m a migrant, I came from South America. I found the American dream, but not everybody is so lucky. So it’s about showing solidarity,” he says.

Enciso likes to say, half jokingly, that this stretch of desert is home to the largest art installation in history. And it keeps growing.

“On average it’s 150 a year. On average. So it’s like a commercial airliner going down every year,” Kovatch says of the death toll in the 20,000 square miles where the Tucson Samaritans and a network of affiliated humanitarian groups work.

“I found the American dream, but not everybody is so lucky."

Activists worry those numbers will grow under the Trump administration. In January, Congress gave Trump more than $1 billion to strengthen existing stretches of the border fence and dramatically increase the number of Customs and Border Protection agents guarding the southern border. This will force larger numbers of migrants to detour through the harsh, remote desert, they say.

Activists also worry about CBP’s approach to their humanitarian work. Earlier this month, dozens of heavily armed agents raided a medical relief camp operated by the humanitarian group No More Deaths. With a small army of PR officials in tow to capture — and tweet — the raid, agents arrested four Mexican migrants who had come to the camp looking for medical help.

It sent an unmistakable message to activists who said they’d been allowed to work relatively unhindered in recent years: The gloves are off and the days of freely helping immigrants are over.

A few miles down South Sasabe Road, Enciso pulls off into a dry wash and heads east. Carved into the desert by the yearly monsoons, the wash twists and turns through the forbidding landscape.

A mile in, the 4Runner — one of two donated four-wheel-drive vehicles the Samaritans use — rolls to a stop. We’ve arrived at the first red dot. It’s where, on July 11, 2016, border patrol agents found the body of Jose Perez Perez, who’d succumbed to hyperthermia.

Dying in the desert is easy. There are the obvious ways, like sunstroke, dehydration, heat exhaustion, and snakebites. Despite searing daytime temperatures, at night it can become bitterly cold, making hypothermia common as well.

But something as simple as a sprained ankle or even blisters can prove deadly if a migrant can’t keep up with their group and gets left behind, as often happens. Further north, closer to Phoenix, thirsty migrants have even drowned after falling into the deep, fast-moving irrigation ditches that keep the state’s cotton and citrus farms verdant oases.

“It's like a commercial airliner going down every year."

The four Samaritans pile out of the SUV into the dusty heat. Like many members of the group, they’re all retirement age. Many Samaritans are transplants from other states who originally came looking for southern Arizona’s dry, warm climate. Most, like Enciso, joined the Samaritans in hopes of providing some measure of relief after hearing about the dangers immigrants face. Although the operation is run out of the Southside Presbyterian Church, it’s an ecumenical affair — the Jesuits help fund its work, and other Christian and Jewish congregations routinely donate food, water, and other supplies.

The Samaritans are part of a broad network of organizations working in the Sonoran Desert to save as many immigrants as they can, and to find the bodies of those they can’t. When they come upon a corpse, they alert local authorities to retrieve it.

While some groups, like the Aguilas del Desierto, include members who were once undocumented immigrants to the United States or who have lost family members to the desert, others, like No More Deaths, are made up of earnest young people whose volunteerism is fueled by outrage. When Emma, a 29-year-old native of Kansas City, Missouri, who works with No More Deaths, first came to Arizona, she didn’t know the border crisis even existed. But having worked in Turkey with aid groups tending to Syrian refugees, once she heard the stories of migrants’ dangerous treks through the desert, she knew she had to volunteer.

“There was this interesting and terrible moment when I moved from Turkey to here and found out basically the same thing was happening,” said Emma, who didn’t want her full name published for fear of being targeted by anti-immigration activists. “It was like, ‘Oh, we’ve militarized the border, we’ve given people no other options, and they have to take these deadly risks. And people are dying.’”

While Enciso looks for a good spot to plant his cross, the other volunteers set to work. Some put gallon jugs of water in a shady spot; others scour the area for signs that immigrants have recently been there.

Given the sheer size of the desert and the countless ways someone might walk through it, leaving water out for migrants might seem like a fool’s errand. But it’s actually relatively easy, thanks to the trail of detritus immigrants leave behind.

It’s not uncommon to find fancy dresses and suits, packed by immigrants hoping to impress potential employers once they arrive in the US.

Empty sardine and bean cans and drained water bottles are common, as are scraps of carpet, which immigrants tie to their shoes to obscure their footprints from CBP agents. Jackets and backpacks lie where they were discarded, bleached nearly colorless by just a few days under the unrelenting sun. It’s not uncommon to find fancy dresses and suits, packed by immigrants hoping to impress potential employers once they arrive in the US.

With the cross planted and water dropped, the Samaritans take a moment to honor Jose Perez Perez, the immigrant who died here, bowing their heads in silence. With only a name, the cause of death, and the date of his demise, there’s nothing for anyone to say.

Their work done here, the volunteers load up their supplies and head farther east down the wash, where they’ll repeat this ritual three more times before noon.

The Samaritans and other humanitarian groups aren’t, of course, the only people patrolling the wild lands of southern Arizona. Twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year, a small army of CBP trucks, ATVs, helicopters, and mounted units keep watch over the desert. There are checkpoints on the roads and highways leading away from the border, and even on the most remote stretches of pavement you won’t go more than 10 minutes without seeing one of the agency’s white and green SUVs.

Since activists first started coming into the wilderness to help immigrants, they’ve had a complicated relationship with CBP and other law enforcement agencies in the region. Some groups, like Humane Borders, have semi-formal working relationships with authorities, which allow the group to obtain permits to place 30-gallon drums of water in heavily trafficked areas.

Most, however, don’t work with authorities, least of all the CBP. Agents will periodically trail Samaritan trucks or stake out water drops to wait for immigrants.

Activists allege that CBP agents routinely target the water bottles they leave, dumping their contents into the sand, slashing them, marking them as poison, or dyeing the water to deter immigrants from drinking it.

Still, in the last few years, activists and CBP seemed to have settled into an uneasy truce of sorts. Samaritans say that while CBP agents still occasionally tail them, they haven't been overtly harassed like they were in years past.

“I fear that such actions and incidents will only deter migrants already putting themselves in peril’s way from seeking water, food, and shelter."

But the raid on the No More Deaths camp earlier this month has activists worried. As part of the warrant CBP obtained to raid the camp, the government revealed that agents had hidden cameras on the trails leading to the site, according to No More Deaths’ cofounder John Fife. Fife said border patrol SUVs have routinely been seen along the ridges that ring the camp property. CBP did not respond to requests for comment, but in a statement after the camp raid, it said it had used “surveillance technology” to spot the four migrants and wanted to “stress the dangers of illegally crossing the border.”

In the wake of the raid, activists with No More Deaths are reevaluating their strategy and say it is unclear whether the camp will remain where it is, be moved, or be ditched altogether in favor of mobile medical aid units.

In a statement released by his office, Rep. Raúl Grijalva, the Arizona Democrat who represents the area around the camp, said he believes the raid “exposes the inhumane approach taken by the new Administration. I fear that such actions and incidents will only deter migrants already putting themselves in peril’s way from seeking water, food, and shelter when they need it most.”

More broadly, activists worry the raid signals a change in CBP’s “sensitive locations” policy. Established in 2013, the policy de-prioritizes enforcement actions at schools, churches, and hospitals. Although the guidance does not prohibit raids in these spaces, the practical effect has been to make them off limits to border patrol agents.

But despite those fears, activists like Enciso say they will continue their work, even if it means adapting their tactics or coming into confrontation with authorities. On Saturday, 35 vehicles took more than 50 volunteers into the desert to mark the Tucson Samaritans' 15th anniversary. The day-long event, dubbed Flood the Desert, served to help migrants as well as to “make our presence known” to local communities and the border patrol, said Deborah McCullough, a Samaritan who took part in it.

“It’s going to continue on, particularly under this administration,” Enciso says of such activity. “Everyone is told to come here, because this is the land of milk and honey. This is the promised land. But apparently, the American dream isn’t for everybody.” ●