Want to study how fake news stories and other false claims spread online? Try Twitter Trails, where computer scientists are training an algorithm to detect misinformation from the way it propagates and how skeptical users respond. Or head over to the Observatory on Social Media, a.k.a. Truthy, where a tool called BotOrNot can detect the telltale behavior of the automated accounts that play a leading role in spreading partisan misinformation.

But there's a problem. These academic projects focus on Twitter because it is an open system that set itself up to let outsiders work with its data. Yet it is Facebook — with 1.79 billion monthly active users to Twitter’s 317 million — that has emerged as the main engine for spreading politically-slanted fake news. But unlike Twitter, Facebook has mostly remained a closed book.

In a survey published last week, BuzzFeed News found that people who say they rely on Facebook as a major source of news were more likely to believe the demonstrably untrue headlines on partisan fake news stories. An earlier BuzzFeed News analysis that found top-performing fake news items related to the 2016 election generated more engagement on Facebook than properly-sourced reports from major news outlets in the closing months of the campaign.

Researchers who study the spread of misinformation say they'd like to help Facebook get to grips with its fake news crisis. But while Twitter makes data available in bulk through an interface that anyone with some basic coding skills can access, Facebook is not nearly as open. Nowadays, if you want to work with Facebook’s data, you usually have to become a contractor, decamp to its campus in Menlo Park, and agree to the company’s terms on what information can be published.

That, for many academics whose lifeblood is the freedom to publish, isn’t an acceptable deal.

“I would love to work with Facebook data,” Takis Metaxas, a computer scientist at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, who heads the Twitter Trails project, told BuzzFeed News. “They really have to own this big mess-up with fake news,” he added. “Not only have they facilitated this, but they have prevented anybody else from helping."

“I always got smiles and a stonewall,” said Micah Sifry, founder of Civic Hall.

As pressure builds on Facebook to exert more quality control over what gets promoted in users News Feeds, some democracy advocates argue that the stakes are too high for this to happen entirely behind closed doors. Facebook is so pervasive in people’s lives, and so influential, they say, that the grip of commercial confidentiality should be loosened in the public interest.

“They are effectively a utility, with the responsibility of a public utility,” Micah Sifry, founder of Civic Hall, a civic technology nonprofit in New York City, told BuzzFeed News.

Indeed, officials in Europe are looking aghast at what happened on Facebook during the US election, seeing the proliferation of fake news as a threat to the democratic process. No wonder that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s brusque denial that misinformation on the platform influenced the election met with an angry response — including from rebel employees who vowed to form their own task force to fight fake news.

Facebook has a crack team of social and data scientists, who know more than anyone else about how people share content on the platform, and the influence it exerts. “They have very talented people,” Fil Menczer, a computer scientist at Indiana University, who leads the Observatory on Social Media, told BuzzFeed News.

Surely, Sifry and others ask, these talented insiders can put their heads together with independent experts and work out how to identify fake news and prevent blatant falsehoods from polluting Facebook users’ News Feeds?

Facebook’s research team was once seen almost as an extension of academia. In the past, the company's scientists have collaborated with leading academic researchers and published their findings in top scientific journals.

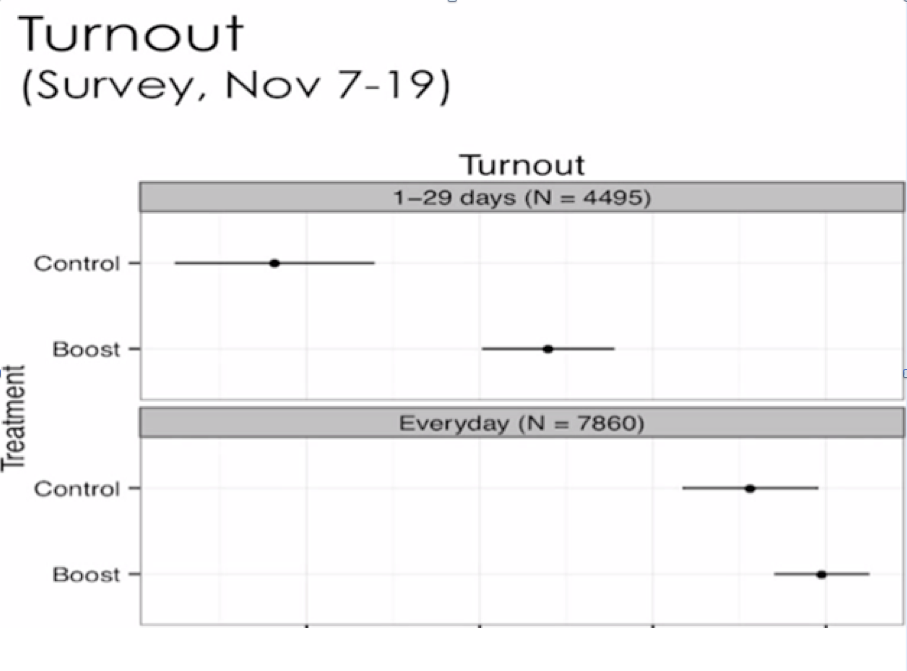

During the 2010 congressional elections, more than 60 million Facebook users received a message in their News Feed encouraging them to vote, and could click an “I Voted” button to share with their friends. Two Facebook scientists, working with a team at the University of California, San Diego, led by social scientist James Fowler, later compared the actual voting records of people who did or didn’t see the message. They concluded that the message alone nudged about 60,000 people into going to the polls, while a further 280,000 people were triggered to vote as the “I Voted” shares spread across the platform.

In 2012, the leading journal Nature published the results this unprecedented experiment, with the bold title: “A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization.”

But in the past couple of years, Facebook’s research into information sharing and its influence on people’s emotional reactions and political engagement has become more opaque.

The turning point came in 2014, with the publication in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) of a similarly provocative paper called “Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks.”

Adam Kramer, one of the the Facebook scientists behind the voting study, had teamed up with psychologists Jeff Hancock and Jamie Guillory, then both at Cornell University, to manipulate what was shown in the News Feeds of almost 690,000 Facebook users. For some, the researchers promoted content expressing positive emotions, while other users were selectively shown posts with a negative tone. The researchers then tracked what these people subsequently posted on the platform, and found that the emotional content of Facebook posts seemed to be contagious.

The effect was small for each person, but huge when considered across the platform as a whole. “In early 2013, this would have corresponded to hundreds of thousands of emotion expressions in status updates per day,” the researchers concluded.

The backlash was swift — and for Facebook it was a public relations disaster. Users objected to having their emotions manipulated, news headlines described the experiment as “creepy,” and PNAS took the unusual step of publishing an “expression of concern” about the research. By including users simply because they had agreed to Facebook’s Data Use Policy, the journal’s editor-in-chief said that the study “may have involved practices that were not fully consistent with the principles of obtaining informed consent and allowing participants to opt out.”

A chastened Hancock, now at Stanford University, told BuzzFeed News that he would today do things differently: While telling people about experiments beforehand could bias the results, he said, it would be better to contact participants afterwards, explain the study’s goals, and then allow people to pull their data from the analysis if they had objections.

Some Facebook users might still be concerned about being made research guinea pigs, but Hancock and other scientists pointed out that similar testing happens on Facebook all the time, as engineers fine-tune the algorithm that decides which posts get promoted in individual users’ News Feeds.

“There’s no such thing as ‘the algorithm,’” Hancock said. “They’re constantly tweaking.”

The backlash against the emotional contagion study made Facebook much more wary about what research should be published, and how it should be framed, several academics who have worked with the company told BuzzFeed News. “There’s no denying that it led to much tighter control over research publications,” Hancock said. That tighter control now hampers the efforts of independent researchers to understand the scope of fake news on the platform, or its impact on users.

Projects studying Facebook’s influence on its users’ political engagement seem to have become particularly sensitive. In the 2012 US election cycle, Fowler’s team and their Facebook colleagues followed up on the earlier experiments in motivating people to vote. Meanwhile, another Facebook scientist, Solomon Messing, experimented with boosting the prominence of shared news stories, compared to other content, in users’ News Feeds. He found that this seemed to increase their interest in politics and likelihood of voting.

Four years later, this research has yet to be published — despite pressure from outside the company. In 2014, with congressional elections fast approaching, Sifry published an article at Mother Jones describing his frustrated attempts to find out more about the research that Facebook ran in the 2012 election cycle.

“I always got smiles and a stonewall,” Sifry said.

Now at the Pew Research Center in Washington DC, Messing told BuzzFeed News he still hoped to someday publish the results. Their brief public appearance was in a video of a 2013 presentation by Facebook scientist Lada Adamic, removed from YouTube at Facebook’s request after Sifry queried the company about it.

Fowler’s 2012 election results also languish unpublished, but he has recently submitted them for review by a scientific journal. He declined to discuss the findings. “However, I can say that some of the delay in publication has been caused by Facebook policies,” Fowler told BuzzFeed News. “If we had been working with our own data, this paper would probably already be published.”

Some of Facebook’s academic collaborators have sympathy with the company’s caution about what gets published. “They care very much about user privacy and user trust in the system,” Clifford Lampe of the University of Michigan told BuzzFeed News. Academics don’t always consider those issues so deeply, he noted, as they prepare to publish their findings.

Lampe has collaborated with several tech firms, studying how people communicate on their platforms, and argued that Facebook is easier to work with than most. “Comparatively, I think they do a very good job of putting their research out to the public,” he said.

Under normal circumstances, arguments about the transparency of a tech firm’s research would be a storm in a teacup — par for the course when academia’s culture of free inquiry butts up against concerns about a company’s bottom line and public image.

But in the aftermath of the 2016 election, and with Facebook’s role in spreading misinformation under harsh scrutiny, these are not normal times.

From what outsiders know about Facebook’s research, the company has the ability to study how fake news propagates on its platform and how that affects users’ emotional states and voting behavior. Its best and brightest may well be working on the problem — which could lead to important changes in the algorithm that shapes users’ News Feeds.

But the company’s critics are not prepared to trust that this is going on behind closed doors.

Writing in the New York Times last month, Zeynep Tufecki, a sociologist of technology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said that Facebook should “allow truly independent researchers to collaborate with its data team to understand and mitigate these problems.”

“Only Facebook has the data that can exactly reveal how fake news, hoaxes and misinformation spread, how much there is of it, who creates and who reads it, and how much influence it may have,” Tufecki wrote. “Unfortunately, Facebook exercises complete control over access to this data by independent researchers. It’s as if tobacco companies controlled access to all medical and hospital records.”

Responding to BuzzFeed News by email, Tufecki stressed that she has no doubts about the expertise of Facebook’s own scientists: “The question is the independence of the research; and lack of conflict-of-interest between the researchers and their findings.”

One problem with Facebook’s research, Tufecki argued, is that it often seems tailored to address the company’s concerns about its public image. Even the controversial emotional contagion study, she said, came after other research had suggested that using Facebook makes people sad and lonely. So the message that positive emotions can be contagious may have seemed attractive to Facebook at the time.

The bullish research on voter turnout, meanwhile, was published at a time when Facebook was playing catch-up to Twitter as a vehicle for sharing political news. More recently, as concern about Facebook’s influence on politics has grown, the message seems to have subtly shifted.

Last year, Adamic, Messing, and another Facebook scientist, Eytan Bakshy, published a study in Science that countered the popular perception that social media is stoking political hyper-partisanship. (Adamic had also mentioned this research in her 2013 talk.)

The paper, titled “Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook,” did find that people are more exposed to content that bolsters their own political opinions, but concluded the the influence of Facebook’s algorithm is small, compared to the political leanings of users’ Facebook friends.

Responding to questions from BuzzFeed News about Facebook’s willingness to collaborate with independent scientists in studying fake news, Jodi Seth, Facebook’s director of policy communications, said: “We’re looking for ways to collaborate with external experts, including academics, on these issues, as we do on all hard questions that relate to our products and their implications for the world.”

“They built a platform and sold it to advertisers as a very influential tool to market stuff to people,” said Sifry. Political campaigns got a very similar pitch. “And then they want the rest of us to believe them when say they don’t have influence on people’s politics,” Sifry added.

CORRECTION

An earlier version of this post misspelled Fil Menczer's name.