WASHINGTON — Few moments in the marriage equality movement have provoked more controversy than the 2009 decision of Chad Griffin to fight California's Proposition 8 in federal court — and to enlist Ted Olson, a key official of the George W. Bush administration, to do so.

Now that the legal bill behind that legal effort has been revealed to be more than $6 million, some are asking questions about the steep fee for the lawyers in the Prop 8 case — especially as a slate of new marriage cases advance through the courts and lawyers jockey for position to argue the one that they expect will ultimately deliver marriage equality to all 50 states.

The debate over the Prop 8 price tag is just one part of a much larger battle within the legal world of LGBT rights: the fight for credit.

Since Griffin, now the head of the Human Rights Campaign, made the decision to go up against Prop 8 five years ago, the landscape for marriage equality has changed dramatically. Griffin, the campaign he put together — the American Foundation for Equal Rights (AFER) — and the lawyers he recruited — Olson and David Boies — are in the midst of a public relations campaign to claim a big slice of the credit for that change. While the fight for credit continues, especially with the forthcoming publication of Jo Becker's book looking at the past five years of the marriage fight, the questions about the costs of the case have percolated under the surface.

The Prop 8 case was an unprecedented moment in LGBT rights history. Boies, Al Gore's former lawyer, and Olson brought a federal case claiming federal constitutional rights — the very case that established LGBT rights groups had been avoiding.

The day the lawsuit, orchestrated by Griffin and AFER, was announced, the leading LGBT legal and political groups issued a rare all-hands-on-deck warning that "the ballot box and not the courts should be the next step on marriage in California" because "the U.S. Supreme Court likely is not yet ready to rule that same-sex couples cannot be barred from marriage."

Griffin, AFER, Olson, and Boies went forward, undeterred, and in so doing, helped change the conversation for marriage equality. Griffin ran the effort like a well-funded candidate runs a campaign — enlisting high-priced lawyers, creating carefully planned media opportunities, and beginning a national fundraising effort to back their case.

For his part, Olson strenuously defends the way AFER and his firm handled the case, noting that Boies and his firm did work pro bono and that his own firm "at the end of the day, because we did so much of it pro bono, was the largest contributor, financially, from that standpoint."

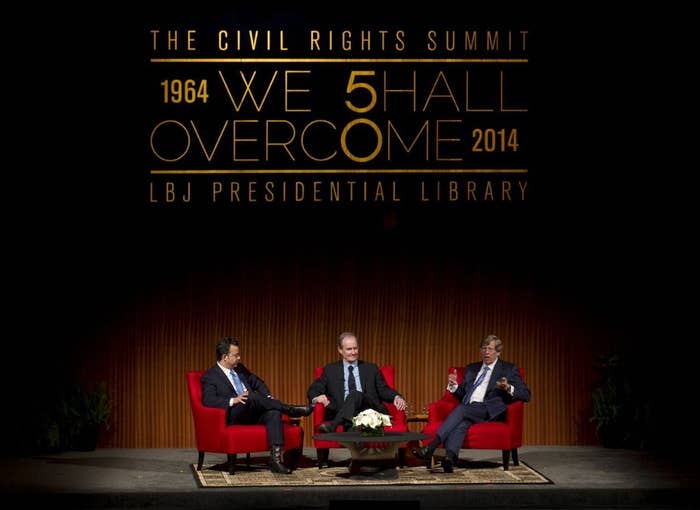

"We didn't want it just to be the venture of a couple of lawyers. But because we got contributors, from liberals and conservatives, it became a substantial endeavor," he said in Austin, Texas, last week before taking the stage at a summit at the LBJ Library celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act. "Lots of people had skin in the game, so that they could care about it, so that they could spread the word, so they could be evangelicals for the cause and so forth."

Boies agreed, adding, "One of the reasons, in a political campaign, and this was in a sense a political campaign — that you try to get people to contribute is not just for the money, it's because once they contribute they become part of what you're doing."

"Even in retrospect, we think it was a very strong and important move to involve people and involve them financially," Olson said.

But that opinion isn't universally held. Kate Kendell, the head of the National Center for Lesbian Rights — one of the groups that had passed on bringing a federal marriage challenge — pushed back a bit against it.

"Our movement would never have reached this catalytic moment without the scaffolding of decades of victories in key legal cases — and those cases could not have been brought without the free legal help from small and large private law firms," Kendell told BuzzFeed.

Ultimately, Olson's and Boies' efforts won back the right to marry that Proposition 8 took away.

But the duo was denied the nationwide victory it had sought when the Supreme Court dismissed the case on technical grounds because the party bringing the appeal — the supporters of Prop 8 — had no authority, or standing, to do so. And AFER's endeavor had a price tag of nearly $13 million, per AFER's executive director, Adam Umhoefer — more than half of which went to Olson's and Boies' firms, as the Washington Blade recently reported.

The $6.4 million price tag runs in contrast to many other legal fights mounted by the LGBT community. Much of such "impact litigation" is brought by nonprofit legal groups like Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders, which brought the case that one of its lawyers, Mary Bonauto, argued and led to marriage equality in Massachusetts. Other such litigation is brought by nonprofit groups working with outside private lawyers working without payment for their services — called pro bono — like Lambda Legal and Jenner & Block's Paul Smith, who argued the 2003 case, Lawrence v. Texas, that ruled sodomy laws across the country unconstitutional.

Many lawyers believe, on principle, that the work on these cases should be done at no or little direct financial benefit for the firms. They consider the cases to be civil rights stands, argued for public benefit.

"The most powerful law firms in the country have a noble tradition of contributing their skills and their resources to major civil rights efforts. It is a way of paying back a profession, and a nation, that have given the firms a great deal — hence the term pro bono publico: for the public good," Tobias Wolff, a University of Pennsylvania law professor, told BuzzFeed. Wolff served as pro bono counsel on appeal to a woman who successfully sued Elane Photography for refusing her service for the photography of her planned commitment ceremony with another woman.

He cited and praised the examples of Paul Weiss representing Edie Windsor in her successful challenge to the Defense of Marriage Act, as well as the effort White & Case mounted on behalf of the Log Cabin Republicans against the "don't ask, don't tell" law.

Roberta Kaplan, the lawyer who led Windsor to victory in the Supreme Court last June, partnered with the ACLU for the case and did the work pro bono, and was quick to emphasize the nature of that work.

"We didn't charge a penny, not a single penny for anything — even including out-of-pocket costs, like expert fees and everything, we paid for," she told BuzzFeed. "The ACLU didn't even charge that, we paid for it."

"Our firm believes it's a very important value of the profession for people in all firms — but particularly in firms as fortunate as Paul Weiss — to give back to the community by doing significant amounts of pro bono work. And that value has been in our DNA from the very founding of the firm, going back to our participation pro bono in Brown v. Board [of Education] up through Arthur Liman's representation [as chief counsel in the Senate investigation] in Iran-Contra."

But AFER's Umhoefer maintained that the group's decision to pay Boies' and Olson's firms was the right one. "I don't think anyone disputes the results — or the return on investment," he said. He cited five reasons the legal fees paid to Gibson Dunn, Olson's firm, made sense.

"One, it was done at a deep discount, and, in David Boies' case, it was done pro bono," he said. The key point, he said, was how their decision to pay the Gibson Dunn team changed the litigation capabilities. "In terms of the rest of the fee structure, it allowed us the resources and the manpower to just utterly demolish the opponents. During trial, there was ongoing discovery. We were being delivered tens of thousands of pages of documents from the opposition — during trial. Because there was actual money behind the work Gibson was doing, they were able to put, just, scores of lawyers on that stuff, working around the clock."

"These guys were taking a chance," Umhoefer said of the environment Boies and Olson entered into. "People have already forgotten what a different world we were living in — and what a big deal this was, really putting their names on the line."

He also said the effort's opponent spent a comparable amount of money as well, and argued the return on the investment — success — was worth the price tag. Finally, Umhoefer also argued that a ballot measure campaign in California would have cost more than $40 million.

"When you look at the way it played out," he said, "I just don't personally believe there's any question whatsoever that it was a very smart use of funds."

There is a middle ground. Woods, the lawyer behind the Log Cabin Republicans' challenge to the "don't ask, don't tell" law, recommended a case-by-case consideration of the financial questions.

"Log Cabin lacked the resources to finance a case like DADT and the firm was willing and able to do the case pro bono, never expecting it would take as long as it did," he said, adding that if a nonprofit organization can afford to pay for its legal services, it should, though few can do so.

Woods also noted that the LCR reimbursed his firm for its out-of-pocket expenses and said that the government, at the conclusion of the case, ended up agreeing to pay $550,000 of the more than $2 million worth of lawyers' time that Woods said went into the case.

"Law firms these days are quick to promote their involvement in these cases to clients and law students," Woods said, noting the benefits beyond payment that firms get from representing LGBT rights causes in an era of increased support for such rights. "They use their work on cases like these to promote not only their pro bono commitment but also their commitment to diversity, their commitment to training, and to high-stakes litigation."

That is, Lambda Legal Legal Director Jon Davidson said, a relatively new development. He has worked with Gibson Dunn and many other firms as pro bono co-counsel in many cases in the time since Lambda Legal started out more than 40 years ago — and in recent years, he said, they've been able to greatly increase the number of lawsuits brought at any given time because of it.

"There was a time when no private law firms would touch a case dealing with the rights of LGBT people," Davidson told BuzzFeed, "and the fact that such talented attorneys as Ted Olson, David Boies, and the other attorneys at their firms have joined the fight is a sign of the remarkable progress we have made."

Since the Proposition 8 case didn't solve the marriage question nationwide last year, dozens of marriage cases have been brought since last summer. AFER — and Olson and Boies — have since joined one of those cases, initially brought in Virginia by local lawyers, in an attempt to take the issue back to the Supreme Court.

After winning at the trial court earlier this year, the case — for which Umhoefer says Gibson Dunn is receiving a "much, much smaller fee" because "so much of the foundation work was done" in the Proposition 8 case — is due to be heard by the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals next month, on May 13.

Virginia has become the site of its own battle. Lambda Legal and the ACLU, which have filed their own suit there, have since intervened in the appeal — over AFER's initial objection.

Those groups, too, are working with an outside lawyer: Jenner & Block's Smith, who is working on this appeal pro bono.

And though the organizations and lawyers have been fighting it out to press these and other cases across the country forward more quickly — and though the fight for credit in the marriage equality battles will doubtless continue — Davidson, for his part, acknowledged the power of all of the legal talent now together before the 4th Circuit. "We have a dream team of lawyers fighting for equality, which is no less than the LGBT community deserves."

But, financial questions will continue. Last week, far away from Virginia, a press release came out the day after a federal appeals court heard arguments on the critical Utah marriage case. That case — brought by a local private firm, Magleby & Greewood, and backed by a small nonprofit, Restore Our Humanity — concerns Utah's ban on marriages between same-sex couples, which was overturned at trial court just before Christmas.

"Fund aims to raise $5 from 1 million people," the release stated, "enabling grassroots participation in historic Kitchen v. Herbert case that … became the first post-Windsor Federal Appellate Argument."