One fall afternoon 17 years ago, Lois Arquette sat in a crowded theater on the North Carolina coast. Lois, who has a short blonde bowl cut and soft round features, watched as the ocean swelled and crashed over a craggy shoreline; an ominous Type O Negative cover of “Summer Breeze” filled the theater. As the movie ticked along, her excitement vanished. She watched, horrified, as a man was gored with an ice hook, blood squirting from his throat along the way.

The film was showing at a massive multiplex, the kind where it’s easy to wander into the wrong theater, and Lois wondered if that’s what had happened. Her novel, upon which this movie was ostensibly set, took place in landlocked New Mexico. It contained no ice hooks, and certainly no scenes of death by ice hook. Still, the plot, at least initially, matched up: After a group of high school friends kill a man, they make a pact to never reveal their secret. Later, the most guilt-ridden of the group — played by Jennifer Love Hewitt — receives an eerie note: “I know what you did last summer.”

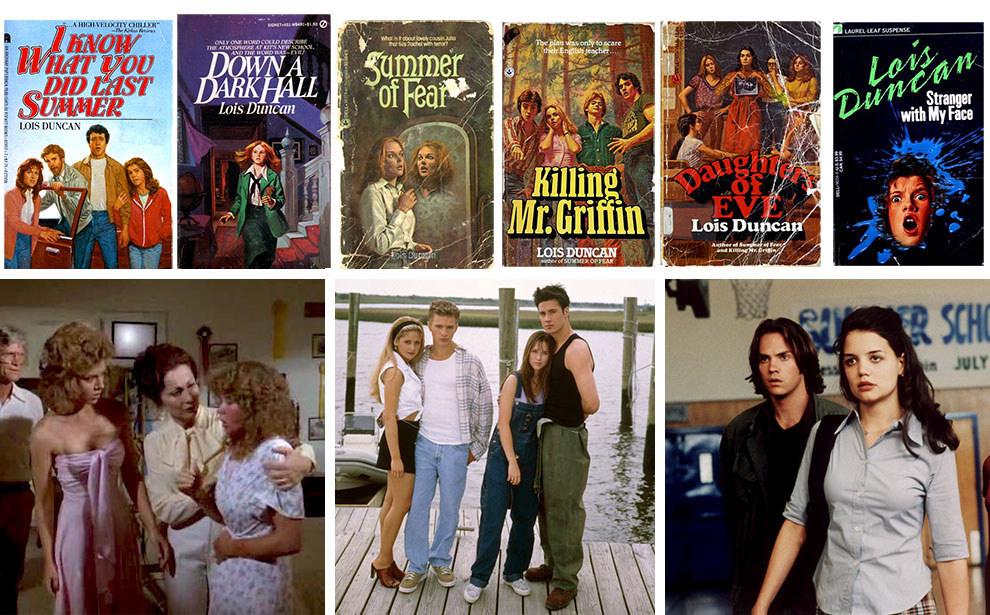

It was a surreal experience for Lois. Since 1966, she had been writing popular suspense novels under the pen name Lois Duncan — an innovator of “throat-clutching suspense,” as the author R.L. Stine described her, one who today has sold "hundreds of thousands" of books, by her own estimate. But she never expected I Know What You Did Last Summer to become a film, much less a $125 million-grossing, franchise-spawning Hollywood blockbuster. When the book was published 24 years before, Lois won no accolades. There were no calls from movie studios. When it was optioned in the mid-1990s, she'd almost forgotten it existed.

Lois wasn’t involved in the adaptation, and as she sat in the theater on opening night, she was astonished. She wrote books that were heart-pumping page-turners about the secret lives of young men and women, lives that were often ravaged by terrifying unknowns. But she helped pioneer a new genre, young adult suspense, because she didn’t want to do stories that were drenched in sex and violence — an almost mandatory component of adult thrillers.

I Know What You Did Last Summer was her first novel to be turned into a theatrically released feature. (Though it was not her last: 1971's decidedly less pulpy Hotel for Dogs was released as a children's film in 2009, while 1976's Summer of Fear was a Wes Craven-directed made-for-TV movie starring Linda Blair and Killing Mr. Griffith became, kinda, Teaching Mrs. Tingle. Twilight author Stephenie Meyer is among the producers of a planned adaptation of 1974's Down a Dark Hall.) Under normal circumstances, this might have been a high point in her career. It wasn’t.

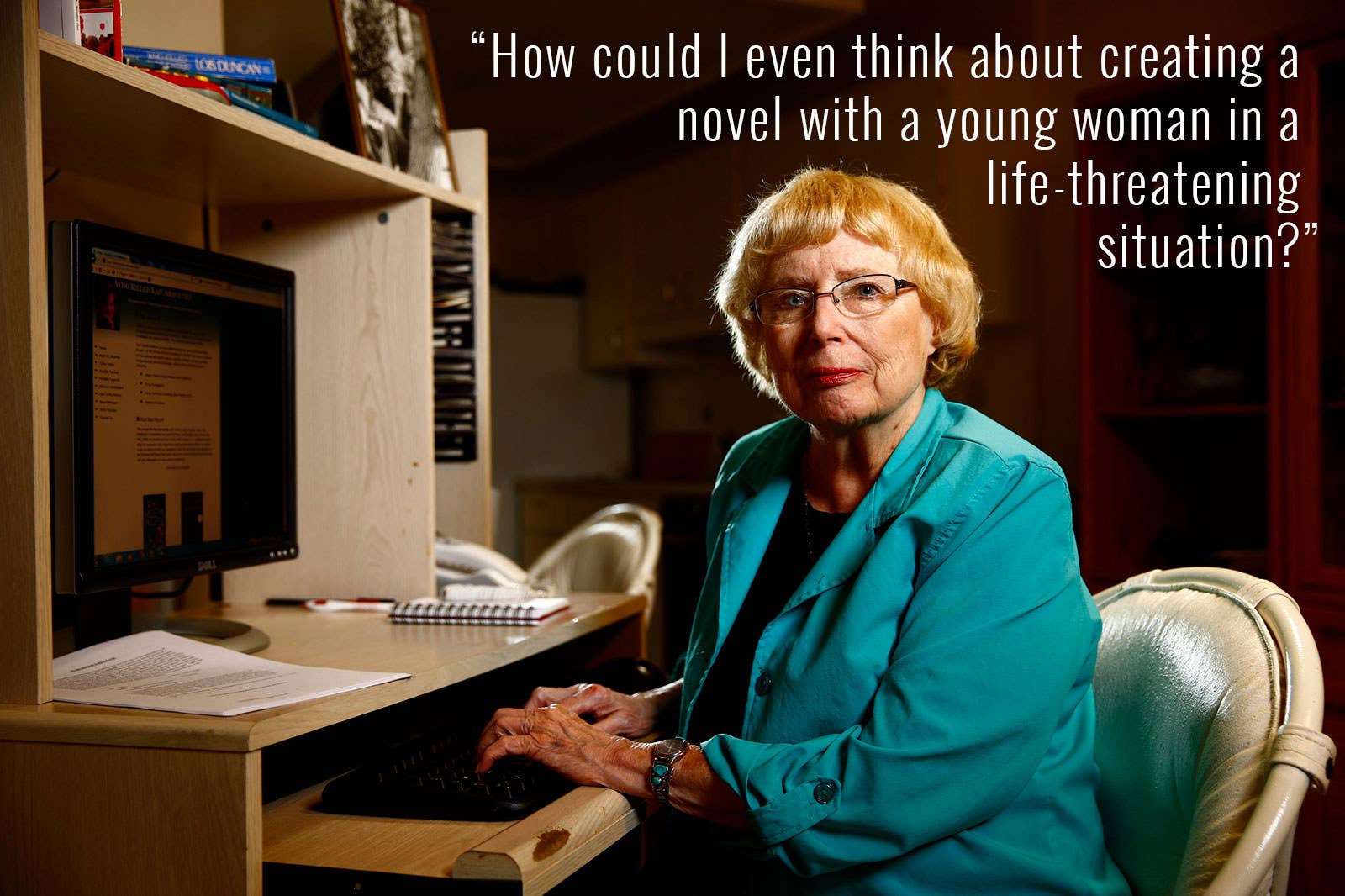

For two decades, she had turned out a thriller nearly every other year; now, she was struggling to complete what would be her last, Gallow’s Hill, and her work was drifting further and further from what she was once known for. She wrote a book about experiments in extrasensory perception called Psychic Connections. She wrote a book about her photographer father's trove of circus photos. There was a good reason the genre had become so difficult for her: the unsolved killing of her youngest daughter, Kaitlyn, in the summer of 1989. “I went weak after Kait’s murder,” Lois said. “How could I even think about creating a novel with a young woman in a life-threatening situation?”

At the time, Lois lived in Albuquerque, N.M., and, unable to write, she focused on Kait. She began by chronicling the grim day-to-day struggles of having a child die violently — of receiving the dreaded late-night phone call and the surreal news that her daughter was killed not in a car accident, as she first suspected, but in a bizarre, unexplained shooting just blocks from downtown.

The investigation into Kait’s murder soon fell apart, and Lois, teetering between grieving mother and dogged semipro sleuth, began hunting down clues — with the help of psychics and a private investigator — that the authorities seemed unwilling to pursue. This 25-year crusade led Lois to the seedier corners of Albuquerque, where, just as she might have done in a novel, she pieced together the hidden life of a complicated young woman.

To this day, Kait’s killing remains unsolved. Over those two decades, theories of Kait’s murder twisted in unimaginable ways, and, in Lois' view, they spiraled into the darkest, most convoluted of mysteries.

“If you look far enough, there’s this thread,” said Lois, now 80. “It’s not necessarily a strong thread. It’s not a chain. The whole thing is like a cobweb.”

In March, when I visited Lois at her modest, two-bedroom condo on Florida’s Gulf Coast, she was warm, self-effacing, and charmingly ornery. After a three-hour interview in her large, vaulted living room, Lois asked what kind of cocktail I’d like. When I asked for a glass of water, she said, “Do you want that in a sippy cup?”

The Arquettes’ home is in a quiet, leafy development a few miles south of downtown Sarasota. Inside, reminders of Kait are scattered around the house: In one bedroom, there’s a gold-framed photo of her as a teenager lying on her side, smiling widely at the camera. In another, she’s a gap-toothed, wildly grinning child; beside this black-and-white image is one of Lois' poems:

We gave our order. We asked for girls,

With frills and flounces and fluff and curls.

The first two came, and how sweet they were,

(All songs and giggles and kitten purr).

We sighed for the parents of little boys,

(All shouts and mischief and dirt and noise).

And prided ourselves on our peaceful state—

And then God smiled. And he sent us Kait.

Long before Kait was born, Lois was an aspiring writer growing up in Sarasota when it was just a lazy speck of a beach town. By the time she was 30, she had left for Duke University, dropped out, gotten married, and gotten divorced. She had two young daughters and a son who, in 1962, as a single mother, she dragged to Albuquerque. Lois had been writing novels for years — her first book, a teen romance called Love Song for Joyce, was published in 1957 under the name “Lois Kerry” — but she never earned enough to live on. That changed in New Mexico.

After being fired from a $200-a-month advertising job (“I wouldn’t sleep with the boss,” she said), Lois found herself in a magazine shop, determined to figure out how to break in as a writer. She bought 22 copies of 22 different confessionals — pulp magazines that published lurid, anonymous secrets that hinged on an easily replicated formula. “I sinned, suffered, got caught, and repented,” Lois explained. She regularly began exposing new, fictionalized sins. One week, she was a kleptomaniac who, at the grocery store, couldn’t help but stuff her purse with overpriced tins of smoked oysters. The next week, she was a mother so frustrated with her constantly interrupted love life that she accidentally killed her colicky infant with an overdose of paregoric. Her most popular story was headlined, “I WANTED TO HAVE AN AFFAIR WITH A TEEN-AGE BOY.”

It was a dark business, but Lois excelled. “I confessed to everything there was,” she said.

Lois' early years were fraught with struggle. She moved every time the rent was raised, which typically meant annually. But the confession stories paid well enough that she bought a house and sent her daughters to ballet school. It was also her real education as a writer — she learned to develop scenes, characters, and plot — and she parlayed her experience into selling stories to women’s glossies and, eventually, a job teaching journalism at the University of New Mexico. With a novel called Ransom, she also helped establish an all but nonexistent fiction genre. In 1966, she married her now-husband, Don, a soft-spoken electrical engineer at Sandia National Laboratories, the facility that designed, tested, and assembled the country’s first nuclear weapons components. Don adopted Lois' three children, and they had two more. Kait was the baby.

The Arquette children grew up in a comfortable, upper-middle class life: a brick five-bedroom house with a big backyard on a quiet street in a safe section of the city. “Life was gentle,” recalled Kerry Arquette, Kait’s older sister. Albuquerque is a big and complicated place, though. Its 187 square miles are a five-hour drive from the Mexico border and encompass the state’s largest city, a place with one of the largest Air Force bases in the country and sizable populations of Pueblo and Navajo Native Americans, Latino immigrants, and Vietnamese refugees who landed in Albuquerque after the fall of Saigon.

The city can also be a dangerous place, one where drug trafficking and addiction have thrived, and where the myriad associated crimes have, said Mike Gallagher, a veteran investigative reporter with the Albuquerque Journal, produced “a deeply embedded criminal subclass that is multigenerational and almost impossible for police to root out.” In the 1980s and ‘90s, the city’s violent crime rates roughly equaled — and at times even exceeded — those of Phoenix and Houston, and even when I visited in February, city officials and editorial writers were debating which television show made the city look worse, Breaking Bad or Cops. (The Journal chose the former; politicians went with the latter.) Recalling a case in which a woman strangled another woman to death, then cut a baby out of the victim’s womb with a pair of car keys, Gallagher put it this way: “This is a really mean town. Shit goes on here that doesn’t make any sense.”

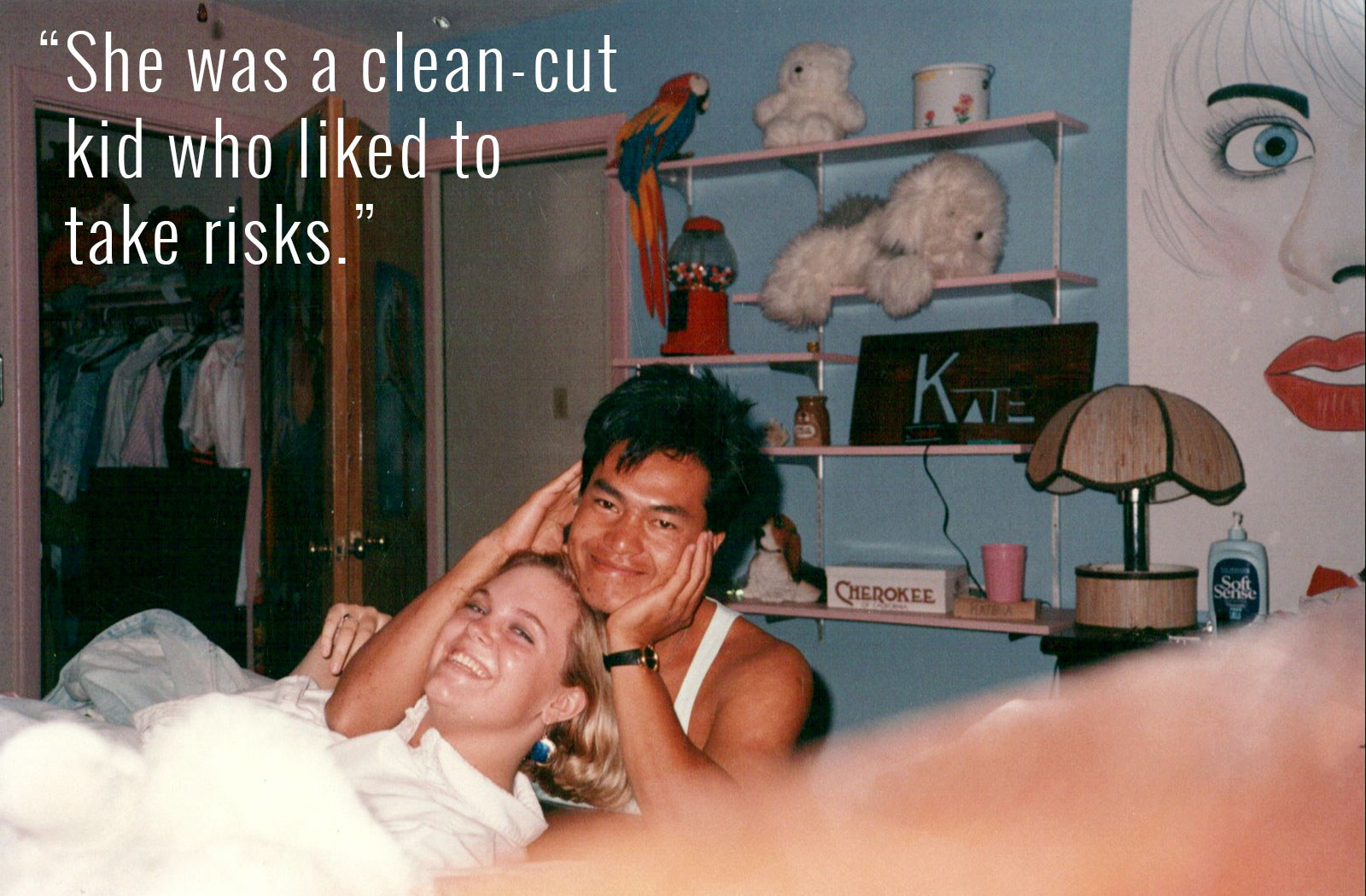

Not that Kait was known to associate with Albuquerque’s criminal class. To her oldest sister Robin Burkin, Kait had always been shy and bookish. She already knew her career path (doctor), and before graduating high school with honors, she was enrolled in classes at the University of New Mexico. But, Robin added, “She did have a side to her that I didn’t know much about.” Periodically, it would manifest in unsettling ways. Kait liked to pick up hitchhikers to acquire their hard-won travel stories, and when she was 16, the family’s mailbox began filling with letters from potential suitors. Lois never untangled the details, but she believed they were probably responses to a singles ad; years later, she would have an unnerving conversation with a prison inmate who claimed to be one of Kait’s correspondents. “She was a clean-cut kid who liked to take risks,” Lois said.

Pat Caristo slid her silver sedan into reverse and inched out of the driveway. It was a clear, warm Sunday afternoon earlier this year, and Caristo, who was a cop before she became a private investigator, had made this short drive to downtown Albuquerque many times over the last two decades. In front of us was a small duplex, the same kind of plain, adobe-style cube that seems to dominate large swaths of New Mexico, and that served as a starting point, 25 years ago, in the final moments of Kait Arquette’s life.

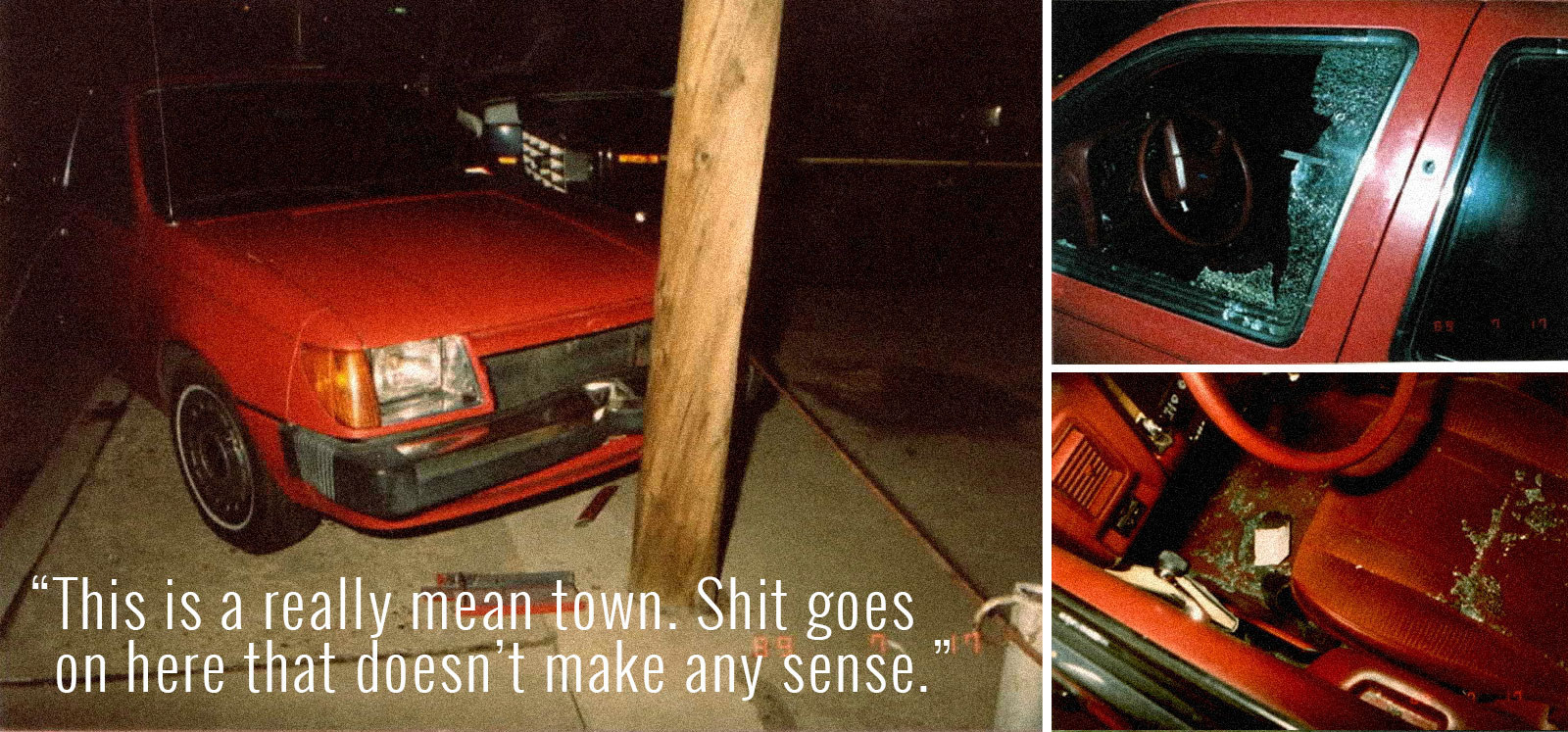

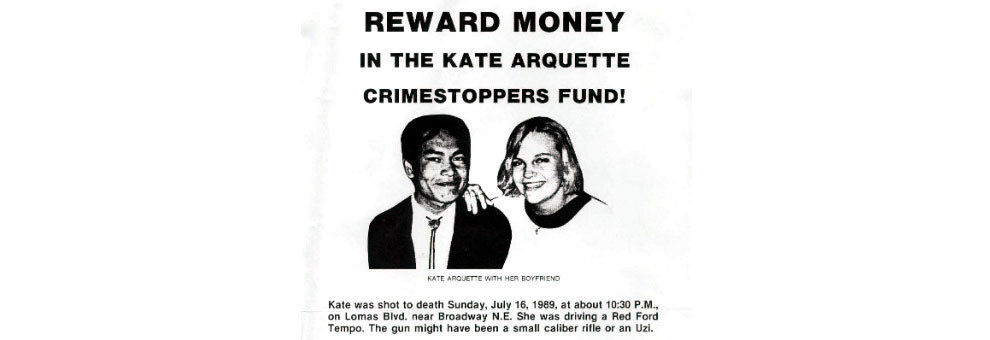

In the summer of 1989, Kait was in the beginning throes of those awkward, fleeting months between high school and everything that comes after: She had just graduated from Highland. She had moved into her first apartment, a studio that she shared with her boyfriend, and she’d gone from rollerskating waitress to bookstore clerk to manager at an import shop. On a Sunday night in July, the 16th, she was at a friend’s condo here having dinner (chicken and green beans), and watching a movie (Valley Girl). When Kait left for the night, she got in her ‘84 red Ford Tempo, backed out of the driveway, and drove one block south to Lomas Boulevard, a thoroughfare that bisects much of Albuquerque’s strip mall sprawl and, just east of the Rio Grande, merges with the mythic Route 66.

As Caristo and I drove south on 19th Street, she narrated Kait’s route. “She would make a left turn onto Lomas,” Caristo said. “It’s 11:00 on a Sunday night. There would be little traffic out here. It had been raining. Everything would be very similar.” We drove east past boxy, suburban-looking professional buildings and arrived, minutes later, in Albuquerque’s eerily quiet downtown, with its clay-colored bank buildings and empty parking lots, its fortress-like federal courthouse and police department. To the east, the Sandia Mountains rose like a dust storm. We crossed a set of railroad tracks and Caristo braked.

According to the Albuquerque Police Department, Caristo said, this was where it happened. Two bullets entered the driver’s side window, shattering the glass and puncturing Kait’s left temple and cheek.

Caristo started the engine and, as she punched the gas, the car drifted leftward across three lanes of traffic. “She is shot twice in the head,” Caristo said. “The car is traveling uncontrolled.” There are few other drivers on the road, and Caristo wanted to complete the reenactment, so she continued drifting across Lomas, into oncoming traffic, as Kait did, toward a used car lot. A driver slowed down and stared nervously.

Approximately 700 feet from where the shots were fired, Caristo parked diagonally in front of a wooden telephone pole. “Here’s where the car ends up,” Caristo said. She pointed to a small indentation. “See that mark? That’s Kait’s mark.”

After the shooting, Kait was rushed to the trauma unit at the University of New Mexico Hospital. She was in a coma and wrapped in so many bandages that she was all but unrecognizable. Lois Arquette was well-known in Albuquerque, and she had taught many in the city’s press corps, so there was intense media interest in the crime, which was also unusual. When hospital officials suggested that the Arquettes hold a press conference, they appeared ashen, sitting at a nearly bare table. Lois shared what little information they had. “From what we’ve been told, they think that a car drove up next to her car,” she said. The assailant fired, and Kait was struck.

Later that day, on July 17, Kait was pronounced brain-dead. Her siblings and parents filed into the hospital room and offered their good-byes. “When I placed my hand on her chest and felt it rise and fall to the steady rhythm of the respirator, it was hard to believe she wasn’t alive,” Lois later wrote. “‘Sleep well, my baby,’ I whispered. ‘Go with God.’”

The murder was treated as a tragedy for the city, and the police promised an all-hands approach. “We don’t care how much manpower it’s going to take — personnel, resources — we’re going to resolve it, bottom line,” the police chief, Sam Baca, told reporters during a press conference. His pledge was punctuated by a six-motorcycle escort at Kait’s funeral.

In the days after the killing, no murder weapon was found and no suspects were identified. Still, the young homicide detective investigating the murder, Steve Gallegos, turned up a few promising clues almost immediately. Back at the adobe condo, Kait’s friend told him that the night of the murder, Kait was furious with her boyfriend. This wasn’t unusual: The arguments had become so routine that just before she died, Kait may have been planning on ending their relationship.

Still, it didn’t seem likely that this was a lover’s quarrel turned fatal. Kait’s boyfriend was a handsome, slender Vietnamese man named Dung (pronounced Yoon) Nguyen. From the little that the Arquettes knew, Nguyen’s migration to the United States had been perilous: He was one of the so-called “boat people,” someone who fled Vietnam by sea after the Americans evacuated. He and Kait met at a coffeehouse a year and a half before, and though he was nearly a decade older than Kait, he didn’t look it, and Lois and Don welcomed him into their home. They spent holidays together. He called Lois “mom.” She took him to the dentist to have an abscessed tooth removed, and tended to him afterward. “He made Kait seem happy,” Lois said.

When Gallegos tracked Nguyen down for questioning, he told the detective that, on the night Kait was shot, he’d been at a bar with a couple of friends; afterward, they gave him a ride to Kait’s apartment. “I waited and waited for her,” Nguyen later told a local reporter. “But she never came home.”

The interview was conducted just hours after the shooting, so Gallegos tested Nguyen’s hands for gunshot residue. When he searched the apartment, he placed just one item into evidence: a small yellow piece of paper with a note that Nguyen said Kait had written him earlier in the day. “Hon, where are you,” the note read. “I know you’re still mad. I’m so sorry OK! I miss you today. I went to mom’s house to return these books. I’ll see ya. Love.”

The residue test came back negative, and Gallegos found no other evidence that implicated Nguyen, a conclusion reinforced by Kait’s brother Brett, who liked his sister’s boyfriend and who went to the police station and told Gallegos as much.

Five days after Kait’s murder, Nguyen was staying with a couple of friends in an Air Force dorm room. When the friends returned from a restaurant, they discovered him on a bunk bed in the corner, moaning. There was blood on the sheets and a 4-inch folding knife on the bed. Nguyen had stabbed himself in the stomach.

Nguyen recovered, and when Gallegos interviewed him one morning a week later, he said he’d been so distraught over Kait’s murder that he tried to commit suicide. “If he had not gotten into an argument with her she would not have been in that area of town or alone,” Gallegos later wrote. Yet Nguyen seemed to have a double life: There was the man that Lois had fed and cared for, and there was the one she heard about from Kait’s landlord, who said Kait had been so frightened of Nguyen and his friends that she asked to have the locks changed on her door.

From Kait’s friends, Lois heard that Nguyen had been involved in insurance fraud in Southern California. The scam is well-known now — a car accident is staged and victims pursue settlements afterward — but in 1989, insurance companies and law enforcement agencies were often unprepared. In the sleazier corners of Orange County’s burgeoning Vietnamese community, the scam had become a highly organized, multimillion-dollar criminal enterprise that involved dozens of unscrupulous lawyers, doctors, and, at the bottom of the chain, recent, often-down-on-their-luck immigrants who could earn hundreds of dollars per accident. The operators who controlled the crime rings could be ruthless, said Leslie Kim, editor of the John Cooke Fraud Report. “It was rule by terror,” she said. “That’s how so many of these groups work.”

Robin, Kait's sister, wondered if his stabbing and Kait’s killing were connected in some other way. “I don’t think people usually stab themselves in the stomach to commit suicide,” said Robin. Her sister’s killing seemed too deliberate to be random.

Robin had always been skeptical of psychics, but when a friend recommended visiting a local named Betty Muench, she agreed. What she found was unexpected: a short-haired, middle-aged woman who conducted her work out of a modern, detached home office. “Betty was extraordinarily ordinary,” Robin said. “She wasn’t even friendly.” Muench channeled the dead through a kind of stream of consciousness that she called “automatic writing.” Her preferred means of communication was an electric typewriter, and for this case, she worked pro bono.

Robin was allowed to ask three questions, and after each, Muench blasted out an answer. When Robin asked if Nguyen or his friends had anything to do with Kait’s murder, Muench wrote, “The situation in which Dung now finds himself is born out of misunderstanding and confusion. It is not as if he will have been the one to do this, but he will seem to know who did it.”

Lois, however, wasn’t just skeptical of psychics, she believed they were con artists. But after Robin shared the transcript, there was no squaring her gut with her head. “Nothing to lose,” is how she described what happened next.

Lois, Don, and Robin drove to the same hospital where they had been just days before, and they found the private room where Nguyen was staying. He seemed groggy, perhaps from pain medication, but alert enough to tell Lois that he wanted to see her and no one else. He put his arms around her neck and thanked her for coming. “He said, ‘I didn’t kill her,’” Lois recalled. “I said, ‘I know you didn’t.’” Lois told him that he knew who did, and that he needed to decide whether he loved Kait enough to tell. He was silent for a moment. Then, Lois recalled, he said, “I know. I am deciding.”

The first thing Lois did was call the detective, Steve Gallegos. After Nguyen recovered, Gallegos asked him to come to the police station for an interview; he asked Lois to come too. “I asked Gallegos, 'What do you want me to do?'” Lois recalled. “He said, ‘Do the same thing you did in the hospital.’” As they sat alone in an interview room, she presented Nguyen with a toy reindeer that he bought for Kait as a Christmas present. She told him how much Kait loved it, and what a sweet gift it was. And she repeated what she said a few days before — that he knew something, and that he needed to make a decision. This time he said nothing.

In Lois' telling, it was around this point that the police investigation seemed to shift. She wasn’t sure what happened, but Gallegos' interest in the troubling details that continued to surface vanished.

There was, for instance, the friend of Kait’s who said she received a startling phone call from Nguyen the night of the murder. “He’s screaming into the phone and he’s saying, ‘Kait dead!’” the friend told Caristo, the private investigator, in a recorded interview. The woman, who did not wish to be identified, had been closer to Kait than Nguyen, and she knew that Kait was upset about the insurance fraud; the couple had traveled to Orange County together when he participated in a staged accident. The friend thought there might be some connection, so she dialed the police and was shuffled to Gallegos. “He just blew me off,” she said. It was only later that she discovered the most striking detail of the experience: The police didn’t notify Nguyen of Kait’s murder until 3 a.m. — several hours after she had that panicked conversation with Nguyen.

Then, there were the phone calls. As Lois was settling her daughter’s affairs, closing accounts and paying bills, she noticed three calls that had been made from Kait’s apartment. Each one was to Orange County, and they were placed on July 17, at the precise time that Kait was in the trauma unit dying. Nguyen had been at the hospital at the time of the calls too, so it wasn’t him. Lois delivered the bill to Gallegos. “I’d call him and say, ‘Were you able to find out?’ He said, ‘No, they’re unlisted numbers. The police can’t get unlisted numbers.’”

In the aftermath of the murder, the note collected from Kait's apartment that she was presumed to have written had been important evidence: It proved that she and Nguyen had settled their argument. Yet when the Arquettes finally saw an original copy of the note, they were floored. Not only was its freewheeling cursive markedly different from Kait’s scrupulously crafted script — examples of which had been provided to the police department — but, even more shocking, there were misspellings and other errors that Kait wouldn’t have made. When the text of the note appeared in Gallegos’ report, it had been cleaned up: “I went to Nam house to retune these books” became “I went to mom’s house to return these books.”

Finally, Nguyen made several stunning admissions about the insurance fraud. In his initial encounters with the police, he said that he knew nothing about it. In fact, he did, and he later admitted to participating in two staged accidents, both of which were planned and paid for by a paralegal in Orange County. He lied because a friend and fellow fraudster told him to. The friend, it turned out, made the three mysterious phone calls from Kait’s apartment. Each one was to the staged accident-planning paralegal.

These admissions were made during an interview at Albuquerque’s central police station. For reasons that remain unclear, authorities didn’t seem particularly concerned; a deputy chief would later describe “claims concerning Vietnamese gang activity” as possibly “nothing more than smoke.” Gallegos, who conducted the interview with Nguyen, seemed sympathetic to his subject. At one point, he asked Nguyen why he thought Lois believed “the Vietnamese” were involved in Kait’s murder.

“She think we did something like that,” Nguyen replied.

“To your knowledge, there’s nothing that would say that anyone in California’s responsible for Kait’s death?”

“No.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

When the interview was over, Nguyen left the police station and, eventually, Albuquerque.

Lois was baffled. Were the police incompetent? Did they know something that they weren’t sharing? “We were having serious doubts about the communication that was going on there and what they were really doing,” Lois told me. In this swirl of desperation and confusion, of grief and increasing frustration, she went looking for answers elsewhere.

Robin had urged her mother to visit the psychic Betty Muench, and she reluctantly agreed. Lois found Muench seemed trustworthy; she didn’t advertise and she still refused payment. She also warned Lois to be cautious with any information she gleaned from their session, especially with the police. (“They’ll chalk you up as a crackpot,” Lois recalled her saying.) It helped that Muench’s plain features bore an uncanny resemblance to someone Lois already knew: a psychic detective she created in one of her books that had been published several years before. “I had the crazy feeling I had scripted the story of my own future,” Lois later wrote.

Lois wondered if there were other honest psychic detectives. She began asking around, and they all had strict policies about only working with law enforcement. To gain access, Lois secured an assignment on the subject for Woman’s Day and after each interview, she would mention her daughter. “They’d say, ‘I’m so sorry, is there anything I can do?’” Lois told me. “I’d say, ‘I don’t know. Is there?’” To help channel Kait, they wanted her belongings, so Lois began mailing remnants of her daughter's life around the country: a pair of gold-rimmed seashell earrings, a purse, a wallet. They responded with possible clues about the murder and supposed messages from Kait that made Lois less convinced that all psychics were charlatans.

Sometimes, these clues led Lois to plan her own risky, crime-solving pursuits. When she got a tip that a “desert castle” may have played some role in the murder, for instance, she grabbed her camera, got in her car, and drove more than a dozen miles into the foothills of the Sandia Mountains. After parking on a dirt road and trudging up a rocky path, it was there, behind a locked gate, with a view of the sprawling city in the distance: the palatial mansion she was searching for.

As if she were a daring — or reckless — teen from one of her novels, Lois hopped the gate and walked through a courtyard. “When nobody appeared to confront me, I continued on under the archway and up the tiled stairs to the bronze-mounted doors of the main building,” she later wrote. She strolled the grounds, snapping photos and observing every detail. “I peered through the windows and saw that the residence was furnished, but there was a feeling of vacancy about it, with deck chairs blown over by the wind; scum in the swimming pool, and tumbleweeds lying in drifts among the marble statuary."

In the end, Lois would walk away undetected, and without finding a thing that was linked to Kait’s murder.

Lois' husband, Don, worried about how hard his wife was pushing. They had, after all, received anonymous threatening phone calls. “At the same time,” Don told me, “I knew she was invested in it, and I knew she could not stop doing this. I knew it was useless to make any attempt to dissuade her.”

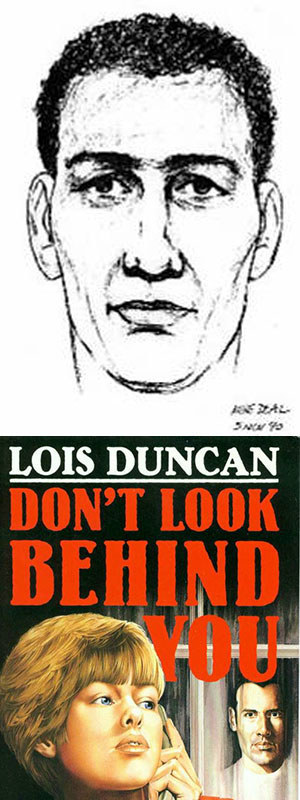

Not all of Lois' psychic endeavors were so dangerous. One of the mediums she worked with, a woman named Noreen Renier, collaborated with a police sketch artist. Lois sent her Kait’s sunglasses, lipstick, and several other items, and Renier sent back a head shot of a possible suspect. The man in the picture looked identical to another character Lois had created, a hit man named Mike Vamp in a book called Don’t Look Behind You. In the book, Vamp drove a Camaro in which he hunted the main female character, who had been modeled on Kait and wasn't yet published at the time of her death.

Meanwhile, the Albuquerque Police Department had been conducting its own investigation, and two men had been charged with Kait’s murder. When the man fired the gun that killed her, the police said, he had been sitting in the passenger seat of a Camaro. His name was Miguel Garcia, but he went by Mike. In an interview with police, a friend offered his nickname: Vamp.

The other man charged with Kait’s murder was Juvenal “Juve” Escobedo. They grew up together in Martineztown, a dusty grid of modest homes and empty lots sandwiched between downtown and Interstate 25. In the summer of 1989, Garcia and Escobedo were 18 and 21, respectively, and in the telling of detective Gallegos, the manner in which they killed Kait was the most horrific, fear-inspiring sort of a crime: a random act of psychopathic violence.

They had been out for a ride in Escobedo’s Camaro — Juve was driving — when they saw a blonde in a little red Ford. As an affidavit for an arrest warrant flatly described it, “Juve dared Michael Garcia to shoot at the female driver. Michael Garcia then pointed a revolver at the blonde female driver through his passenger window, which was open, and fired several shots.” A term that was getting more and more attention at the time was used to describe their crime: drive-by shooting.

When Escobedo and Garcia appeared in court — and on televisions across Albuquerque — they looked like scrawny kids who had sauntered into a body-building gym for the first time. Each was outfitted in a short-sleeve, pale blue jumpsuit. Escobedo had a wispy mustache and a mop of curls; Garcia’s face was framed by short, pressed-back black hair. Lois told a television reporter that she was hopeful, but shocked at the arrest. “I just simply couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” she said.

Yet the case was in trouble as soon as it began.

The friend who offered Garcia’s nickname also claimed to have been in the Camaro’s backseat the night of the shooting, and he told police about the revolver that killed Kait; he’d seen Garcia grab it from between a box spring and a mattress at his family’s home. Yet it turned out that the friend couldn’t have been in the backseat — he was incarcerated. When police found the revolver, it was missing a bushing and a spring. The gun was inoperable, and it had been that way for months. “The guy that wasn’t there chose that as the murder weapon,” recalled Gallagher, who uncovered the scandal for the Albuquerque Journal.

Less than two weeks later, the charges were dropped.

So the police took a different approach. Instead, detectives focused on neighbors who claimed to have heard Garcia talking about the crime, as well as another man who told a cop and jail guards, that he too witnessed the murder from the Camaro’s backseat. When a grand jury was convened, he backed off the claim and said the confession was coerced. He only made the statement, he said, after the detective interviewing him turned off a tape recorder and threatened him. “If you don’t want to cooperate,” the detective allegedly told him, “then I’ll just send you to prison and set you up [on] the death penalty.”

The grand jury didn’t believe it, and a month after the charges were dismissed, Escobedo and Garcia were indicted for first-degree murder. Garcia had remained in jail, but Escobedo, who had been freed, was nowhere to be found. More than a year passed, and he was like a ghost. One day Lois would hear Escobedo was in Albuquerque, the next, maybe he fled to Mexico. All along, the police said they were diligently searching for him. “We didn’t know who to believe,” Lois said.

Then, one Tuesday in the spring of 1991, nearly two years after Kait’s murder, the Arquettes were summoned by the district attorney, Robert Schwartz, a wiry man with a cartoonish, super-sized mustache and a balloon of gray-streaked hair. The charges, Schwartz told them, were being dismissed. He still believed that Kait was the victim of a random drive-by shooting and that Garcia and Escobedo were guilty. But some of the witnesses had started waffling; Schwartz believed they had been intimidated. “They became pretty much unusable,” he said. “The other problem was, the defense attorneys had gotten on to this Vietnamese connection. It has a much better motive than our case.”

But, he added, “The trailhead pretty much stops there.”

None of it made sense. If the motive behind the “Vietnamese connection” was better, Lois wondered, why did it seem like Gallegos hadn’t bothered to look there? She knew better than to accept an intriguing psychic tip without corroborating evidence, but she still wondered about Escobedo and Garcia. Where had Juve gone, and why had he never been found? Did they have something to do with Kait’s murder, or were the stories of police coercion true?

It's not as if the city of Albuquerque or its police department had a matchless reputation. Gallagher recalled how, in the 1980s, APD’s intelligence unit began tracking attorneys who sued the department, along with the reporters who scrutinized it. When the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit seeking the disclosure of the files, the police department burned them. Later, a police officer who dressed as a Japanese assassin was convicted of murder and bank robbery, and the mayor, along with a powerful state politician, were found to have participated in a kickback scheme during the construction of a courthouse. “I used to wake up every morning wondering if city hall had been sold,” Gallagher said.

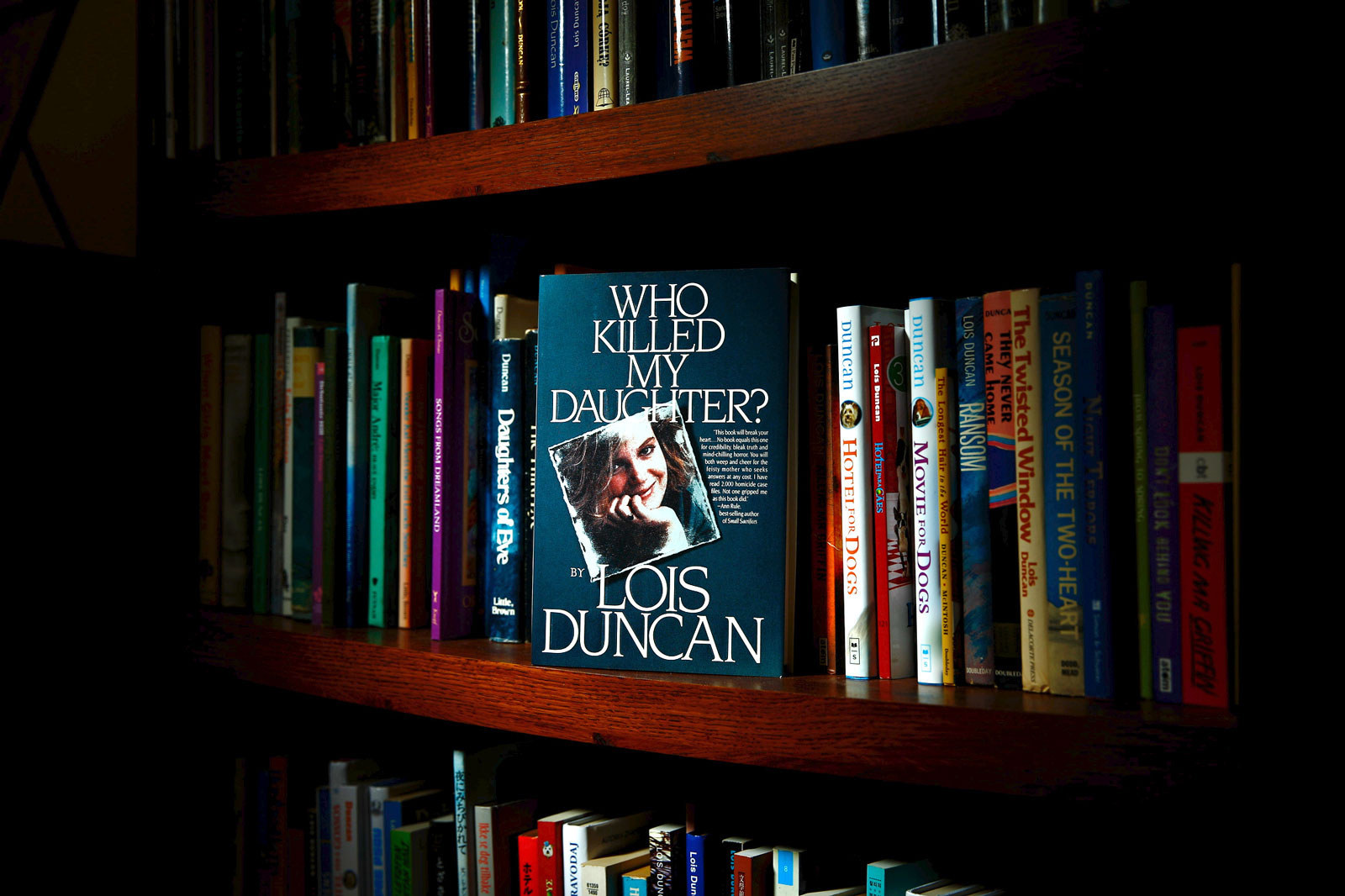

Lois' nonfiction account, Who Killed My Daughter?, published in 1992 under the name Lois Duncan, wove together the murder, the disturbing events that followed, and her struggle to make sense of it. She was deeply critical of how law enforcement handled the case, and the police department responded in kind. When a local reporter asked the deputy chief of investigations about the book, he shot back, “I don’t read fiction.”

On the national media blitz that followed the release of Who Killed My Daughter?, Lois appeared alongside the district attorney, Robert Schwartz, on Larry King Live for what was to be a sparring match between a prosecutor and the outraged mother of a murder victim. As Lois prepared in her hotel room, she was nerve-racked. Schwartz didn’t just perform in the courtroom; he had a side gig as a stand-up comic. She developed a debate strategy that hinged on one crucial fact: “I knew more about the case than he did,” she later wrote. “I vowed to myself that I was not going to continue to be cast as grief-crazed housewife creating monsters out of dust balls.” Then, a last-minute call from her husband about a psychic tip scrambled everything: Kait’s killers might turn on each other. Don’t alienate the police, Don warned her. Grudgingly, Lois vowed to appear as nonconfrontational as possible.

The seven-minute segment that followed was odd. Lois had prepared for a fight, and instead she delivered what sounded like a canned statement. Afterward, Lois recalled, Schwartz asked for an autograph.

A couple of years later, after the paperback edition of Who Killed My Daughter? was published, Pat Caristo, the private investigator, was watching television one day when she saw Lois on Sally Jessy Raphael. When the show’s phone number appeared, Caristo picked up the phone.

Caristo had spent most of her life in law enforcement, first as a police investigator in Philadelphia, then as a detective with the University of New Mexico’s police department, and, finally, with an organized crime commission convened by the governor. She eventually started her own private investigations business in Albuquerque and was hired by a lawyer drumming up business in a grim new market: the drive-by shooting-related personal injury claim. The Albuquerque police had always used that term to describe Kait’s killing, so the lawyer asked Caristo to dig into the case. This eventually led her to parse every detail of the crime scene. What she found was disturbing.

The sequence of events that led police to Kait’s red Ford was brief — probably less than two minutes. It began at about 11 p.m. the night Kait was killed, with a plainclothes detective who had been busily ferrying witnesses to the police station on another case. He was nearly done for the night when he saw Kait’s car. Her body was slumped over, so as he drove by, he didn’t see it. Instead, he thought there had been an accident, so he drove on and radioed dispatch to see if anything had been reported. There was nothing, so he turned around and, eventually, discovered Kait. Already, potentially critical evidence had vanished from the scene.

When the detective initially drove by, he saw more than one car next to the wooden telephone pole. After calling dispatch and making the U-turn, only Kait’s car remained. A man who lived around the corner from the scene would later tell police that after hearing what sounded like gunshots, he peeked out his front window and saw a Volkswagen bug zipping away from the scene. But the detective didn’t see this; there were no late-night high-speed chases through downtown Albuquerque. Instead, the detective found a man standing near Kait’s car. “He happened to be passing by,” the detective later explained in a deposition.

The man was Paul Apodaca. At the time, he was in his early twenties, but he was already accumulating an alarming criminal history. Throughout the ’80s, he was charged with committing multiple violent attacks against women, including robbery and beating a young girl with a baseball bat. In one case in 1990, he fired a .22-caliber pistol from the window of his car at a transgender person walking down the street, striking the victim in the back. Apodaca’s car was a Volkswagen bug. A few years after that, a strange and terrifying headline appeared in the Journal: “MAN RAPES STEPSISTER TO GET INTO PRISON.” Apodaca’s younger brother had been convicted of murder, it turned out, and Paul wanted to protect him while he was behind bars. So he raped a 14-year-old relative, and was sentenced to nine to 20 years in prison.

At the scene of Kait’s murder, Apodaca’s contact information was taken. Then he left. When Caristo discovered this, she was astonished. Standard procedure would have required police to run Apodaca’s name, she said. Officers would have seen that a few months before Kait’s murder, he had been found on the side of University Boulevard with a nearly empty bottle of Jim Beam, a 12-pack of Budweiser, and two .22 pistols. Apodaca and an uncle had been there shooting; at what, precisely, is not specified in a police report. “All they had to do was call his name into APD records,” Caristo said. “That’s investigation 101.”

When Caristo saw Lois on Sally Jessy Raphael, she didn’t hear Apodaca’s name once. So she dialed the hotline. “They knew nothing of it,” Caristo said.

One day in October 1995, not long after the Arquettes hired Caristo, she found Apodaca at the Bernalillo County Detention Center, where he was being held for the rape conviction. When they sat down in an empty visitor’s room, Caristo was surprised by what she encountered: He was mild-mannered, clean-cut, and, at least initially, candid. He told Caristo about that July night in 1989: He’d been on the way to a friend’s house when he saw Kait’s car on the side of the road, so he pulled over. The detective arrived moments later, and the men approached the car together. “Then I asked him, ‘Who was with you?’” Caristo said. Apodaca’s pleasant demeanor seemed to vanish. “Who said anybody was with me?” Caristo recalled him saying.

This was, of course, a crucial question. A Volkswagen had been spotted leaving the area immediately after the shots were heard. Was it Apodaca’s? The colors didn’t match: He told Caristo that his was orange, while the witness described one that was gray. Still, to Caristo, this was a coincidence worth investigating, because if it was his, and it had been driven away, someone else was behind the wheel.

As Caristo deconstructed the crime scene investigation, Apodaca was just one piece in a rapidly expanding puzzle. She discovered, for instance, that no bullets or shells were ever recovered from the crime scene, and that only a few fragments were found in Kait’s body. Had somebody cleaned them up or had they been missed? The forensic pathologist who examined Kait suggested that the two bullets that killed her were fired from a small-caliber pistol, yet when Caristo examined photos of Kait’s car, she noticed a large bullet hole in the car’s driver-side door that appeared to have come from at least a .38.

Finally, when she interviewed the first two cops to arrive at the scene — the plainclothes detective and a uniformed officer — they provided starkly conflicting accounts of those first moments: The detective said it was the officer who collected Apodaca’s information. The officer said it was the detective. Apodaca, meanwhile, said there was no uniformed officer even there. “From this moment, we don’t know what happened,” Caristo said. “There is not one, literally, one confirmed fact.” Caristo assembled her analysis into a 75-page document and delivered it to the Albuquerque Police Department. She never heard back.

The questions she raised, though, took the case in entirely new and alarming directions, and spawned all manner of grassy knoll-like speculation. Was there a relationship between Apodaca, the “Vietnamese connection,” and Escobedo and Garcia? Had the crime scene been derailed by incompetence or by a cover-up? Had Kait stumbled onto something even more sinister than insurance fraud?

In the years after Who Killed My Daughter? was published, Lois appeared on several supernatural-oriented television shows to discuss her psychic experiences. She worried these would diminish her credibility with authorities, but since the shows were popular, she thought they would ultimately help solve Kait’s murder. “I hope you don’t say we’re psychic addicts,” she told me. “I don’t want to be known as one.”

Lois never stopped documenting Kait’s murder, and though it took far longer than she ever anticipated, last year she published a follow up to Who Killed My Daughter? “I kept waiting for an ending,” she said. Part memoir, part true crime, One to the Wolves laces together the peculiar experience of being a talk show newbie with the shoe-leather detective work of Caristo and others. When I visited, she had just heard that One to the Wolves, which was published as an e-book, would be released as a paperback. She was excited. “It’s one thing to do a book about a sobbing mother,” she said. “It’s another thing to say that the whole system is corrupt.”

She told me that she was more certain than ever that Kait’s killing was planned, and that the apparent errors made at the crime scene weren’t, in fact, errors. In her view, these were by design. “I don’t see how anybody with a brain in their head could think it was random,” she said. The who, what, where, and why of this conspiracy are sprawling and circumstantial; they involve a garage that once operated as a chop shop, heroin discovered at the import store where Kait worked, and an evolving list of characters and motives. “There are more and more reasons that she could have been killed,” Lois said.

Caristo, meanwhile, is certain that Kait was targeted. “You’re driving along and somebody gets you like that?” she said. “It was close, and it was bang, bang.” But she’s less convinced about everything else. In her telling, the simple scenario goes like this: The police screwed up in a multitude of ways and, realizing the potential for a civil lawsuit, sought to “minimize” their errors, as Caristo put it. If it were complex, someone from outside the police department controlled the case. When I asked which theory she tended to believe, there was a long pause, and she sighed. “I don’t know,” she said. She started to say something, then trailed off. “I would like to think it’s the first, but I don’t know.”

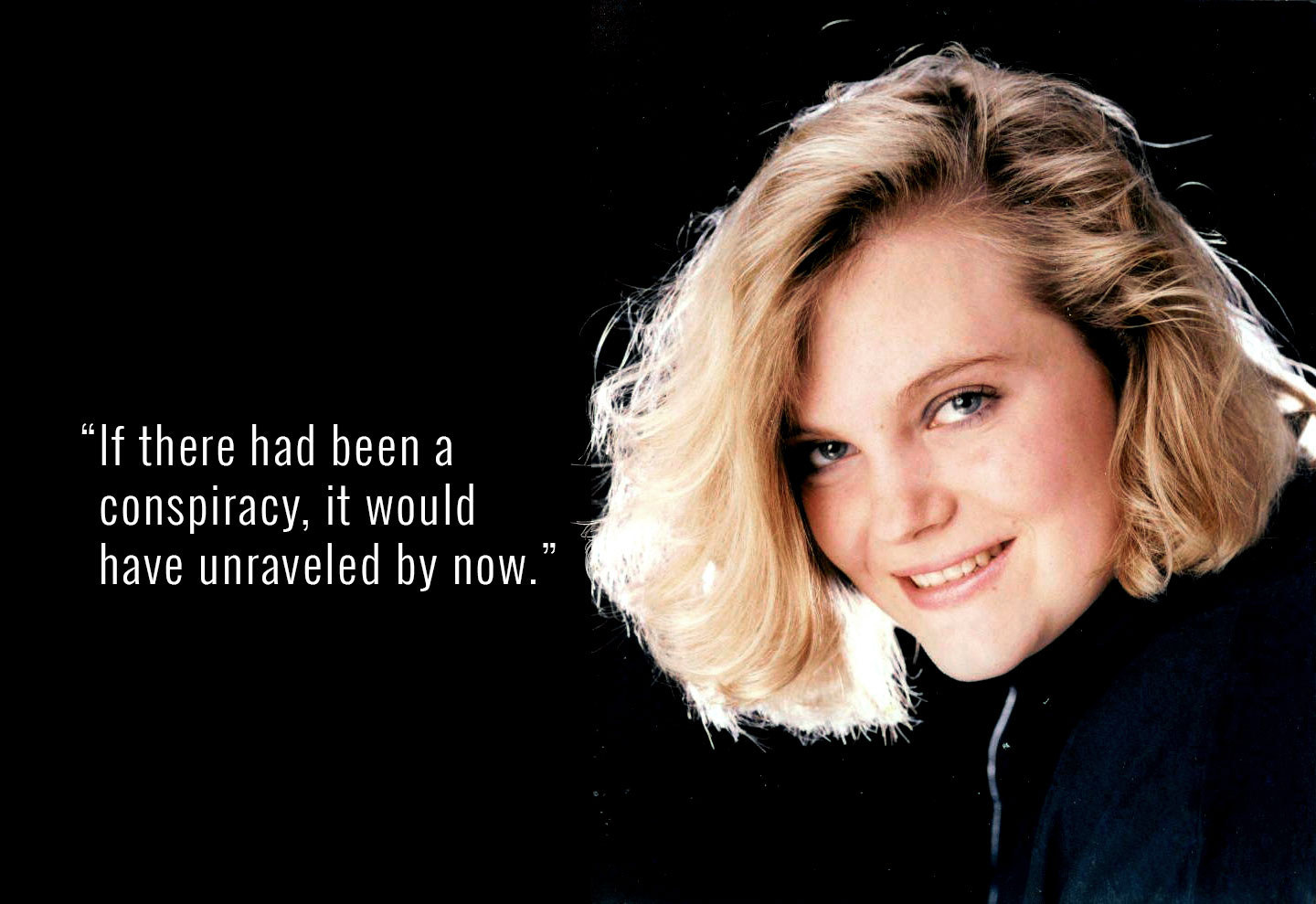

Gallagher believes the case was destroyed by incompetence and bad luck, among other things: An almost off-duty detective didn’t question a man who should have been questioned. An inexperienced homicide detective failed to eliminate possible suspects. “What you’ve got is a mess,” he said. “Unfortunately it’s a mess that’s caused more by the police culture. If there had been a conspiracy, it would have unraveled by now. Conspiracies cannot pass the test of time. Especially with cops.”

In the Albuquerque Police Department’s view, the case was not bungled by its own, but by Lois. “When she puts out stuff that’s not factual, it’s not helping the case,” Major Anthony Montano said. Montano would not say which details were not factual, nor how they had “compromised” APD’s investigation, as he put it. He would not discuss other specifics of the case, though he did add that a cover-up has never been substantiated. When I asked if it had been investigated, he told me, “To my knowledge it was. I can’t say for certain.”

After leaving Albuquerque, Dung Nguyen eventually settled in Northern California, where he is believed to live in a beige two-story townhouse in a leafy subdivision in suburban San Jose. When I knocked on his door in February, he wasn’t home, but a young woman who said she was his stepdaughter was. She patiently listened as I explained who I was and why I was there. I asked if she would give a letter to her stepfather explaining as much, and she smiled and agreed. I never heard from him.

In 2012, Paul Apodaca, who had been released from prison for the rape conviction, returned with a 12-year sentence after splitting open his girlfriend’s forehead and stealing her car. In March, I wrote him asking if he would discuss the case. He did not respond.

I knocked on the front door of a one-story brick house in Martineztown where I heard a relative of Escobedo’s might live. A man with a wild Fu Manchu mustache told me that he was Escobedo’s older brother. Juve, he said, lived in a back room for a while, but he rarely heard from him, and he didn’t even know how to reach him. I told him about the story I was working on and gave him my phone number in the unlikely event that he did.

A half hour later, my cell phone rang. “This is Juve Escobedo,” the voice said. By 4:30, Escobedo and his teenage daughter, McKayla, were sitting in the lobby of my airport hotel. Escobedo scarcely resembled the just-old-enough-to-drink kid of the television news clips. He was tiny, with a paunch and a receding hairline, faded jeans, and a gray T-shirt. He had never discussed the case with a reporter before, and as we talked, he spoke slowly and deliberately, never taking his eyes off mine; occasionally, he leaned forward to emphasize a point. A couple of times, he teared up. McKayla, whose eyes were attached to the smartphone in her hands, periodically glanced at her father and grinned.

Escobedo was raised in a dirt-road village in central Mexico; he arrived in Albuquerque with his mother on Jan. 1, 1979, when he was in third grade. Before the winter of 1990, life was pretty good: He got in some trouble — a DWI — but nothing on the scale of what was coming. “I was a happy kid,” he said. He’d known Miguel Garcia and the two other guys for years. One was a neighbor whose sister he had a crush on; another would help wash the Camaro in lieu of paying gas money for rides.

In Escobedo’s telling, he was at his sister’s apartment the first time he heard of Kait’s murder. They were watching the news one night when the story flashed across the television. It caught his attention because of the location — one of his brothers lived nearby. “I never knew that down the road I was going to be blamed for it,” he said.

When Escobedo was arrested at his girlfriend’s apartment six months later, he said he told the police the same thing over and over: "You arrested the wrong guy." After he was released, he ran into the two friends that talked to the police, and both told the same story: They were railroaded. Escobedo believed them, but their friendships were over. He saw Garcia too, but they never talked about the murder. “He’s never told me if he did it or if he didn’t do it,” Escobedo said. When the charges were reinstated, Escobedo said he didn’t flee the state or the country; he didn’t even leave Albuquerque. “I’d rather take my life into my own hands and control it,” he said.

Escobedo went on to work in construction and have a family, and when his son and daughter came of age, he would tell them about how he had once been accused of murder, but how it wasn’t true. He moved away from Martineztown, but would periodically hear about the three men he was arrested with: One died of a drug overdose. Another was homeless. Garcia hadn’t done well either. He wouldn’t speak to me for this story, but Escobedo said he tried to commit suicide after the murder charges were dropped, and he had been in and out of prison in the years since.

Not a week goes by, Escobedo said, that he doesn’t think about what he called the “gorilla on his back” — the murder accusation that never went away — or about Lois, whose first book about Kait he read, and who he once saw on a talk show discussing the case. He didn’t like that she seemed to rely so heavily on psychics, but he said he understood her desperation. Since Escobedo’s own 20-year-old son, Andrew, died in a construction accident two years ago, he’s found himself thinking a lot about the loss a parent feels when a child is killed. “I kind of relate to Ms. Lois in that sense,” he said. “We didn’t get a chance to say good-bye to our son either.” Still, he understood the stark difference between them. “I know who took my son’s life,” he said. “I know how it happened. Where it happened. When it happened. Unfortunately, she doesn’t know. She’s going to live the rest of her life like that. It’s not fair.”

Back in Sarasota, Lois wasn’t sure what to make of Escobedo. He and the others had surely been arrested to close the case as quickly as possible, she conceded, but she still believed that they may have been involved, if only on the periphery. Yet she and Escobedo shared a similarly bleak view about the future of Kait’s case: Whatever happened to her could very well remain a mystery. “The Albuquerque Police Department does not want this case solved,” Lois said. “That’s what we’ve come to believe, although that’s the last thing we would’ve ever thought."