The La Brea Newsstand in West Hollywood sells a lot of things — cigarettes, gum, incense — but the wooden racks that line its prime real estate along the sidewalk sit empty. What once offered passersby a weekly wave of celebrity tabloid headlines is now a shrine to how far the industry has fallen.

It’s gotten so dire for the celebrity tabloids that even the almighty stalwarts, People and Us Weekly, have had to cut staffs, close offices, and consolidate operations to save costs, according to interviews with current and former employees.

“The younger generation is gone,” Kent Brownridge, former general manager of Us Weekly for 23 years, told BuzzFeed News from his house in Connecticut. “They are never going to read magazines. They grew up with their iPhones. They want to know what happened in the last hour, not in the last week.”

Consolidation of the tabloids, most recently with the purchase of Us Weekly, has led to closed bureaus and mass layoffs in the wake of a drastic drop in magazine rack sales in recent years.

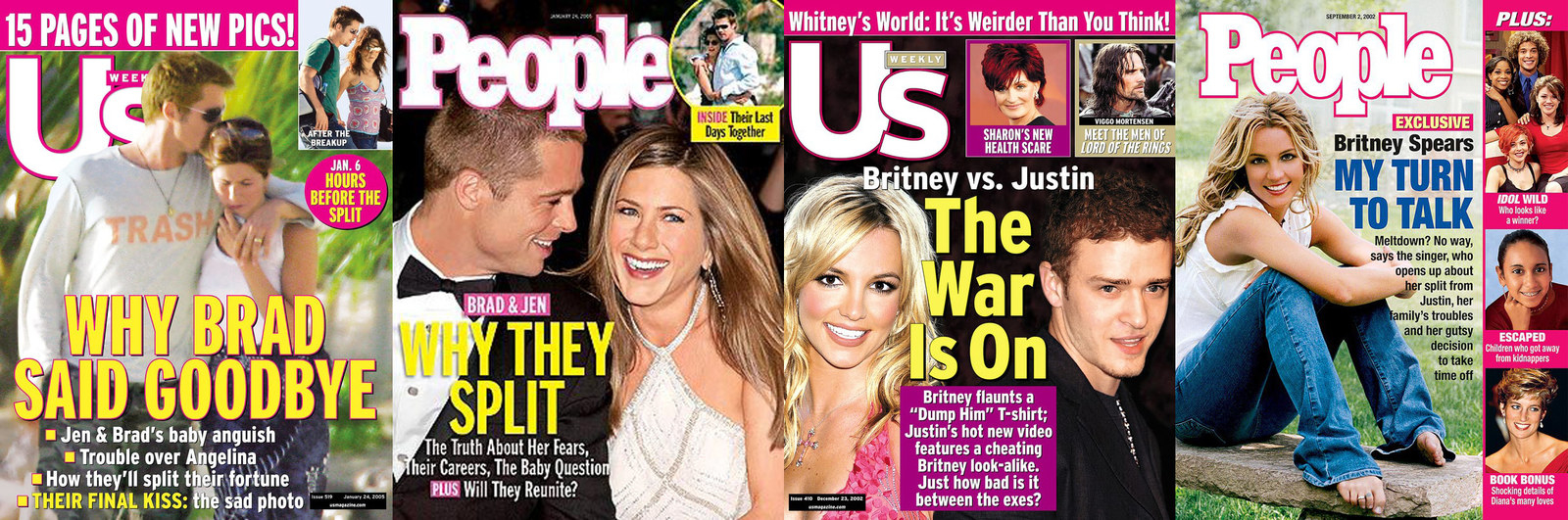

During the heyday of 2006, People was selling an average 1.6 million copies off the rack each week. It was followed by In Touch Weekly at 1.2 million and Us Weekly at 1 million copies. Life & Style, National Enquirer, and Star were each selling more than 700,000 issues each week.

Then the Great Recession hit heading into 2008. By 2016, Us Weekly wasn’t even breaking 200,000 average weekly newsstand sales, and People had fallen to 521,000. In Touch dropped to 306,000, Life & Style to 129,000, and the National Enquirer to 238,000, according to the Alliance for Audited Media.

“No one is even looking up at the magazines," said former People managing editor Larry Hackett, referring to store checkout aisles. "Everyone is just looking at their phones."

Which begs the question: Could the glossy tabloid covers that have long pined for our attention at the checkout stand disappear altogether?

“You can get everything you want on Facebook and you hardly even have to link through to the publication itself,” said Jonathan Taplin, professor and director emeritus of the Annenberg Innovation Lab at University of Southern California and author of Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy. “It’s not that there isn’t an interest in gossip. It’s just that you can get all you need from your social media feed.

“Who can compete with free?”

Before the age of the iPhone and Facebook, little was free and, outside of television, the weeklies had a virtual lock on the celebrity news pipeline.

Back then, before the age of sponsored posts on Instagram and carefully crafted personal brands, celebrities were more accessible and not as managed as they are now, said Kevin Dickson. He spent 10 years working in the trenches of In Touch and Life & Style, starting as a freelance reporter and ultimately becoming executive celebrity director.

“When it started, it was fun,” he said.

It was also fast-paced, highly competitive — and lush.

Buoyed by exploding rack sales, where most profits are made, magazines were flush with cash, sending reporters around the world to stay at luxury resorts to chase celebrities and ingratiate themselves with sources. It wasn’t long before no expense seemed too outrageous if it meant beating the competition.

“There was a lot of money on the table back then,” Dickson said. “We could literally take the crappiest source, the third banana on a sitcom, to Hyde (nightclub), get bottle service, and have a horrible boring night with a $1,700 bar tab.”

Reality TV stars were also increasingly thirsty to either maintain their 15 minutes of fame or push into another celebrity arena.

"That was the thing: to win the weekly battle against all the other publications. And it was very intense."

Dickson recalled being assigned to an exclusive Mother’s Day shoot with Kris Jenner at her house, where her then–relatively unknown children were to serve her breakfast in bed. A phone call from his editor and the promise of a cover for Kim Kardashian changed everything in an instant.

“It was a time when Kim couldn’t hold a cover and my boss called and said, ‘If you can get Kim to do a setup in the backyard and say, "I have cellulite, so what?" we will give her the cover,’” Dickson said. “Cut to 35 minutes later, we are out by the pool taking a photo of Kim in her bikini. We did unretouched photos with her declaring on the cover, ‘I Have Cellulite, So What!’ After that, we did so many covers [with the Kardashians], it was crazy.”

The tabloid machine kicked into overdrive, fueling six-figure payouts for paparazzi photos and an all-in approach to every aspect of covering the world of celebrity.

And as mags like Us Weekly, which had a younger-skewing audience, started to encroach more and more on territory long held by the reigning People, the tabloid war started to get white-hot.

Hackett, who worked at People from 1998 to 2014, eight years as general manager, said that when Us and the other celebrity magazines stepped into the arena, “we had to raise our game.”

Bidding wars over celebrity wedding access, a new baby announcement, or a never-before-revealed story became some of the most contentious battlegrounds.

“We were about maximizing sales each and every week. And the way you do that is you have to get the most gripping celebrity news for that week and put it on the cover,” Brownridge, formerly of Us Weekly, said. “When [celebrities] would get married or have a baby, they would call up all the magazines and ask how much they would bid. And then People would bid all its dollars and the rest of us would say, ‘Fuck that.’ And People would get it.”

The tabloid war, most famously waged between People and Us Weekly, didn’t stop there, with magazines buying up photos solely to prevent the competition from using them.

“People was very defensive and would spend crazy money on things just to keep it out of the other magazines’ hands,” said Brittain Stone, who ran Us Weekly’s photo department for 15 years. “That was the thing: to win the weekly battle against all the other publications. And it was very intense.”

But when celebrity-centric sites like TMZ, Just Jared, and Perez Hilton hit the scene, the fast times of print started to come to a screeching halt. Competing against a website that could post more than 20 headlines an hour became no match for a print weekly with an anemic web presence.

The proliferation of social media only made things worse. Seemingly nowhere was private. A visitor from Wisconsin tweeting a picture of a movie star shopping at a Hollywood grocery store could generate just as much buzz — for free.

As rack sales took a dive, so too did resources and budgets. And that’s when the deep cutting began.

In recent years, easily more than 100 staffers in the tabloid industry have lost their jobs, either as operations scale down or consolidate through acquisitions. During Hackett's tenure at People alone, five bureaus were closed, he said.

"It was such a dark time," said Howard Breuer, who worked at the magazine. "If you were among the masses that were leaving, or if you were hanging on for a little bit longer, everyone had the feeling it wasn't going to be the same magazine anymore."

And there wasn’t much hope of the situation improving. With fewer resources, tabloids had an even harder time finding new traction with younger readers, many of whom consume most of their media on mobile.

“There was definitely a cost-cutting imperative and we sort of realized we lost our way in terms of news gathering,” Hackett said.

Brand value, meanwhile, has continued to ebb. Us Weekly, for example, was reportedly valued at between $600 million and $750 million at one point before being purchased by American Media, Inc. (AMI), on March 15 for $100 million, joining the company’s other celeb-related titles Radar Online, Star, Globe, OK!, and the National Enquirer.

A few tabloids, including People, In Touch, and OK!, have their own apps, and everyone maintains a presence online and on social media, but the priority has never wavered from print, experts and former employees say.

Cooper Lawrence, radio host of the The Cooper Lawrence Show, said there was a reluctance early on among the tabloids to accept digital as an essential part of their future.

She recalled approaching one of the main editors at Us Weekly about posting a promising podcast to their website. The response: “Web is not the future of this magazine, the magazine is. And if it is not in the pages of the magazine, we are not going to focus on it,” Lawrence said she was told.

“It was such an antiquated way of looking at journalism and media…the idea that the internet was just temporary and it was a fad,” she added.

Like newspapers, tabloids have been trying with varying degrees of success to branch out into other mediums to expand their audience, be it ventures in television programming, apps, and online partnerships.

“The strategy is: this is not just a print magazine anymore. This is a 360-degree brand and we are going to develop our brands to survive the test of time,” said Dylan Howard, chief content officer at AMI which is on track to soon complete its acquisition of Us Weekly.

At People, the overall audience has also gotten "much, much bigger" due to growth on digital platforms, moves into television production, and a streaming network, the magazine’s editorial director, Jess Cagle, told BuzzFeed News.

"Everybody knows what the People brand is, but our audience for Snapchat Discover that we are really focused on is very different than our audience buying the magazine on newsstands," he said.

Still, he said, efforts are underway to stabilize declining rack sales "because it is still a great way to make money."

For example, Brownridge said each issue of Us Weekly during his tenure cost an estimated 75 cents to print and ship, but then were sold off the rack for $4.99 to $5.99.

That kind of profit margin has made print a hard, if not impossible, source of income to to wean off of. And Sandra Carreon-John, managing director for M&C Saatchi Sport & Entertainment, told BuzzFeed News there are still traditional advertising hold-outs who, despite counsel to the contrary, insist on print.

“We hear it all the time. ... They want it in print," she said. "Even though their target audience might be 24–34 males who may not be reading their information in print, they still want the ad in print.”

As AMI’s stable of titles grows, Howard said the company is uniquely situated to appeal to more of those advertisers "by presenting a portfolio of brands that reach the full gamut of readers, from a 30-year-old woman through to an 80-year-old woman."

“It’s still a newsstand-driven business," he said.

But no matter how far the tabloids dig in on reinvigorating their print products, they will still have to deal with the growing number of people like 25-year-old Brittney Turner, co-owner of Sorella, a women's clothing boutique on Melrose Avenue.

"I'm just so glued to my phone,” she said during a recent stroll on Fairfax Avenue near West Hollywood. “The only time I pick up the magazine is when I'm in line at the grocery store, but I don't buy it."

It still may not be all doom and gloom for tabloids. Cagle said that while the industry is certainly "doing a lot more with a lot less than we did 10 years ago," new hires are being brought on for other editorial ventures.

"I talked to almost every celebrity I ever admired...most people don’t get to do that."

But it's too late for the likes of Ingrid Meilan, who is among the many who didn't survive the latest round of consolidation and cost-cutting. A senior reporter at Us Weekly for 10 years, she lost her job after AMI closed down the magazine's West Coast bureau.

It was a fast-paced job Meilan fell into after a chance encounter with a British Us Weekly editor while working as a sales clerk at Fred Segal. After telling the editor she read every issue of magazine, the next thing Meilan knew, she had a job covering the club scene in Los Angeles.

“It was a dream job,” Meilan said. “I am super grateful that I had it. I got to go to the Oscars, the Globes, and every award show. I talked to almost every celebrity I ever admired...most people don’t get to do that.”

And it will probably stay that way going forward, according to Brownridge, who spent more than two decades in the eye of the storm at Us.

“The glory days are over.”