The Home Office created a rapid response strategy to solve cases that were generating bad publicity for the department amid mounting criticism of its hostile environment approach, BuzzFeed News can reveal.

Established by then home secretary Amber Rudd in 2017 — before the Windrush scandal broke — senior immigration staff are given the freedom to make decisions outside of the rules and quickly grant visas and citizenship to individuals whose cases are reported in the press.

Cases solved just days or weeks after receiving media attention include several uncovered by BuzzFeed News, such as that of Cynsha Best, who was suddenly informed she wasn’t British after being born in the UK, and Valentina Hynes, told to leave her British husband and toddler son behind. Notably fast U-turns were also made in the cases of Brian White, a student with a place at Oxford University whose citizenship had been refused, and Shane Ridge, a joiner born in the UK wrongly told he couldn’t stay in Britain.

While the ability to solve some cases quickly is welcomed by lawyers, they also feel it introduces a double standard for immigration cases. The tiny minority lucky enough to receive media attention get a bespoke service while the vast majority have no means of contacting the Home Office for a proper conversation about poor decisions, let alone reversing them.

Since appeal rights were removed in many cases — and legal aid removed in most immigration matters — social media, petitions, and journalism are becoming the only hope of seeking redress for many people caught up in the immigration system. Fast-tracking high-profile cases to undo poor decisions risks cementing criticism of the wider department as being inflexible, obsessed with the rules and caring little about individuals.

David Lammy MP, who campaigned on behalf of victims of the Windrush scandal, told BuzzFeed News: “This is deeply cynical from the Home Office, which is demonstrably more concerned with avoiding the scorn of the press than with helping the most vulnerable people caught up in this country’s archaic immigration system.

“The lucky few who get coverage in the media are handled by competent, compassionate, and fast caseworkers. But the reality for the majority of constituents dealing with the Home Office bureaucracy is months or years of waiting, poor decision-making, and an increasingly hostile environment.”

The Home Office insists that all cases are treated the same way. However, a source close to the former home secretary confirmed that the strategy for dealing with cases highlighted in the media changed in 2017 at a time when online campaigns for individuals were “coming thick and fast”. The source said Rudd was pragmatic about the role investigative journalism could play in uncovering the worst decisions.

According to the source, Rudd felt she wasn’t able to get to the bottom of what had gone on in many cases that were reported in the media or where campaigns went viral, and leaks against her had become so prolific that she didn’t trust that she was getting the right information.

Something would appear in the media, Rudd would say “what on earth is going on here?” and when she didn’t get a satisfactory response, her frustration built up, the source told BuzzFeed News. The gap between the home secretary and the frontline decision-makers was so large that it was too easy for people to say “we’ve checked; it’s fine”. Tasking senior staff with investigating was her way of getting answers and solving problems, though she is also understood to believe the new responsiveness to cases exposed in the media ultimately created the snowball effect that caused her downfall.

The Home Office has had the power since 1971 to solve cases outside of the rules — but previously the culture, when approached by journalists with a bad decision, was to dig in its heels and appear tough, rather than acknowledge a problem and reverse it. When Theresa May was home secretary, any changes to a decision in an immigration case typically came through the courts or other ordinary appeal procedures.

Lawyers began to notice the shift in strategy when they started receiving phone calls from home office staff within 24 hours of their client receiving publicity. They say the callers, who are helpful, polite, and give direct phone numbers and email addresses, are in marked contrast to the typical Home Office experience. In some cases, clients have been waiting five years or more to speak to someone at the Home Office, and then their case is solved 24 hours after publicity.

By the time the Guardian began reporting on the Windrush scandal in November 2017, the strategy was already in place. It meant that many individual cases were solved relatively quickly, but the systemic problem was not addressed. For people like Paulette Wilson, a woman who used to cook for MPs and was told wrongly that she was an illegal immigrant, the media reports meant her papers were processed “unusually quickly”.

While “the Daily Mail test” — whether a policy or decision would be judged favourably by the newspaper — has been commonplace in senior Home Office circles for some time, Rudd was also responding to more liberal media. She felt that the idea of deporting those who shouldn’t be deported was “just horrific” and a “justifiable outrage”, and that a strategy to solve cases was a way of having some impact.

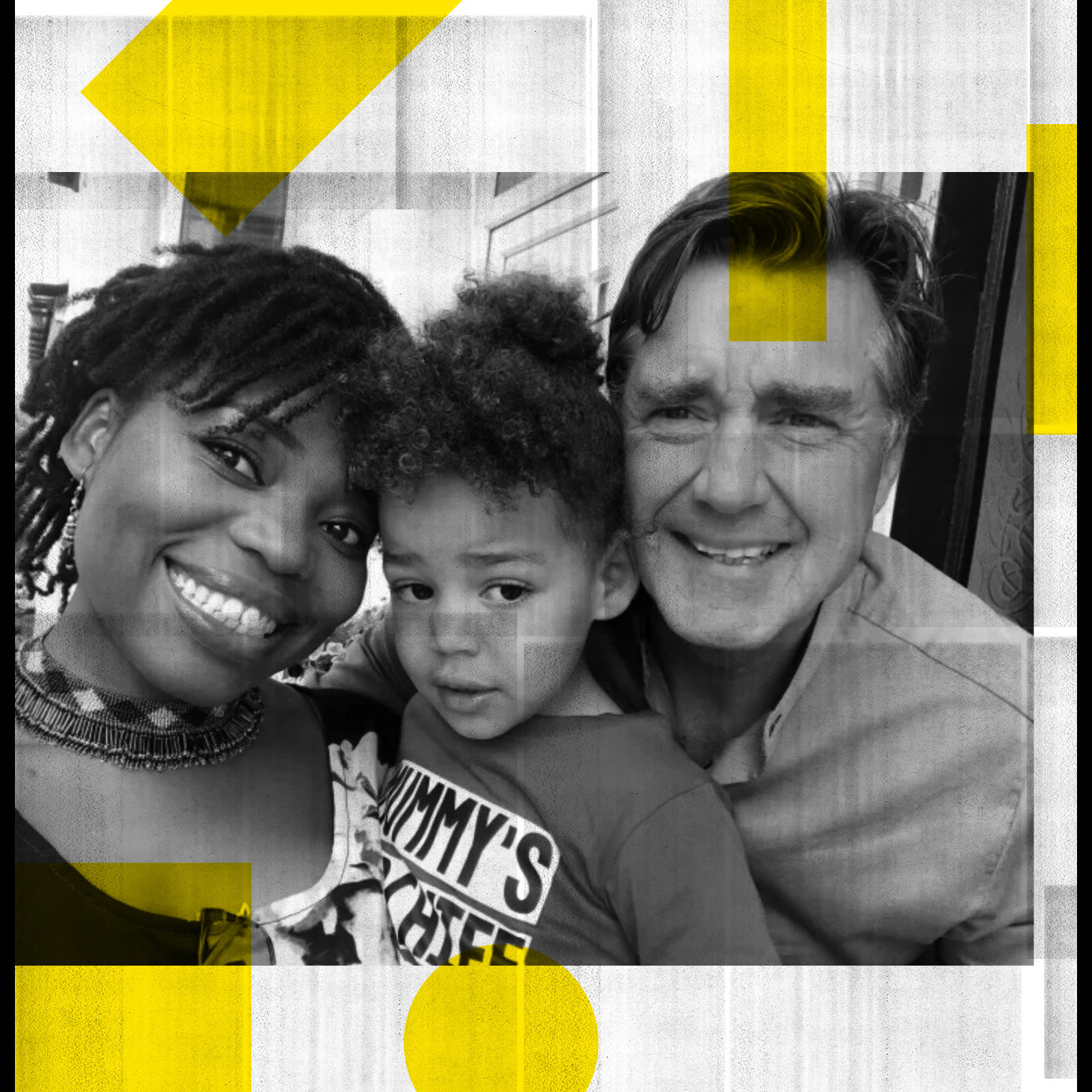

The story of Valentina Hynes, first reported by BuzzFeed News earlier this month, showed the strategy in action. Hynes was initially denied a visa when she settled in Yorkshire with her British family after her husband had a heart attack on a visit home. She had thought her only hope was waiting for an appeal date next year, but shortly after BuzzFeed News published its story, her lawyer, Naheed Akhtar, was contacted by a senior caseworker wanting to resolve the situation. A few days later, Hynes was granted a visa.

Akhtar said the double standard was blatant. “I’ve got two other cases refused today and one is identical to the Hynes’ case. They don’t want bad publicity.

“The decisions aren’t thought through at all. It’s flawed. It’s the hostile environment — they’re just trying to meet their targets and send back as many people as possible. But when there’s publicity they do a U-turn.”

Akhtar said the Home Office offered no substantial account of why their position had changed. “They never give an explanation as to why they change their mind. They can’t explain because they’ve got nothing to say. They know what they’re doing is wrong.”

Hynes’ experience is one that will be familiar to anyone whose case has received public attention in the last year after being caught on the wrong side of the Home Office. A petition starts to go viral, a reporter picks it up, the press office is contacted for a response, and within days of media reports, a reversal of the decision is underway.

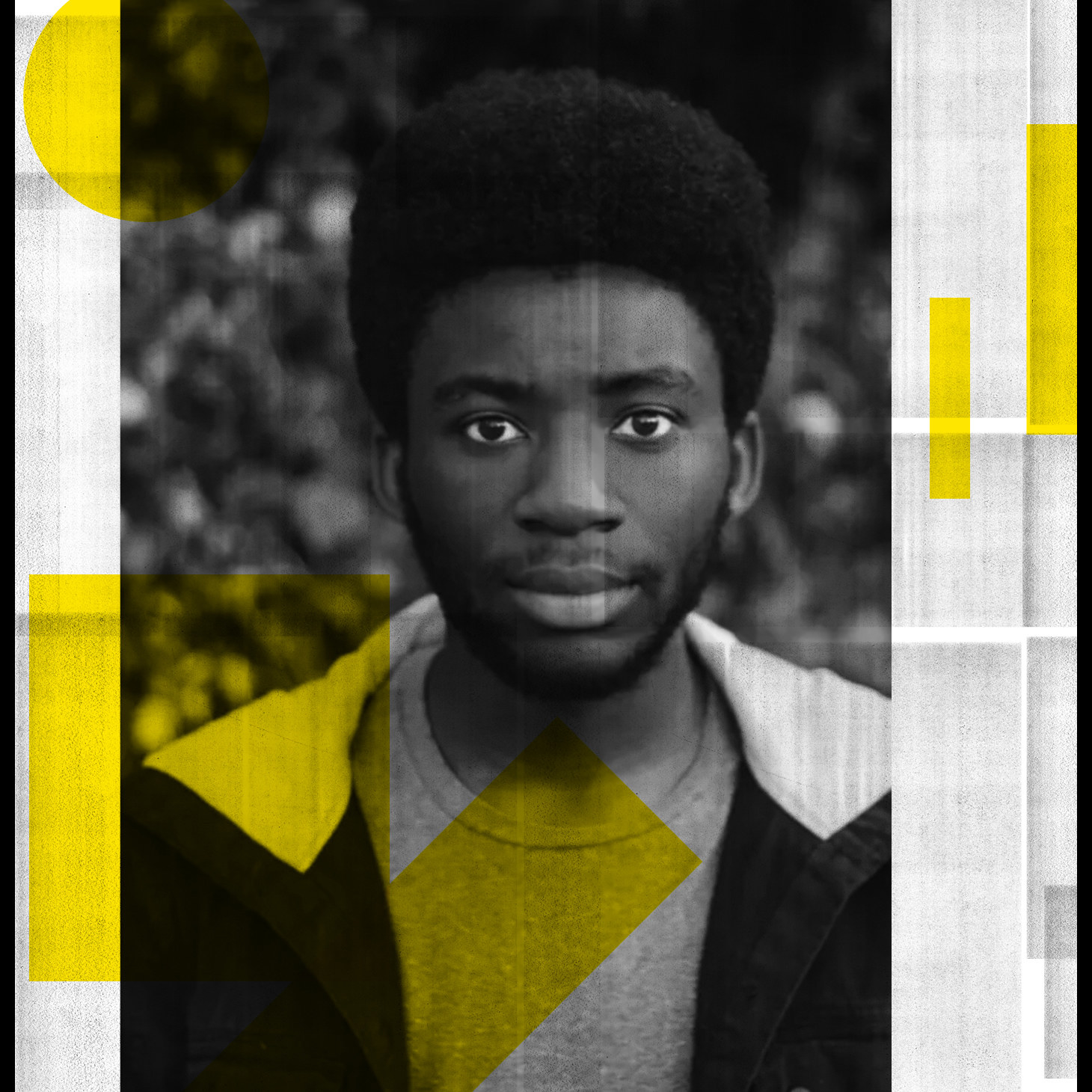

When a friend of Brian White, a promising young student with a place at Oxford, started a petition to fight the Home Office’s decision not to grant White citizenship or a visa, the timeline was very similar.

White’s lawyer, Louis MacWilliam of Blacks Solicitors, recalled: “It had been six months and we hadn’t heard anything and it appeared to be going nowhere fast. There was no indication a decision was imminent until the Change.org petition, which hit the news big time. Then it all happened extremely quickly.

“He was lucky because he was going to Oxford — there could’ve been lots of other people going to Nottingham Trent or wherever that wouldn’t have had the same response. It’s not that unusual a case. I thought we wouldn’t get a decision for a year.”

MacWilliam said the government’s handling of the case marked a shift from his previous immigration work. “It was the first time I’d ever experienced anyone from the Home Office calling me to proactively solve a case and this person who was senior by his own introduction. His whole manner was completely different. Normally when you call the Home Office, they’re very rude or you can’t get through. If you’re sending a letter, you don’t normally get a response and you certainly don’t speak to anyone.”

The Home Office response caught him by surprise. He had initially cautioned against trying to solve his situation through the media. “I’m not proud of this, but we were saying it might jeopardise the case. We couldn’t have been more wrong. We didn’t know there would be this change in attitude towards publicity.”

MacWilliam says the caseworker also had the power to exercise discretion in ways he had not seen before “by disregarding some immigration requirements”, such as the life in the UK test and proof of maintenance.

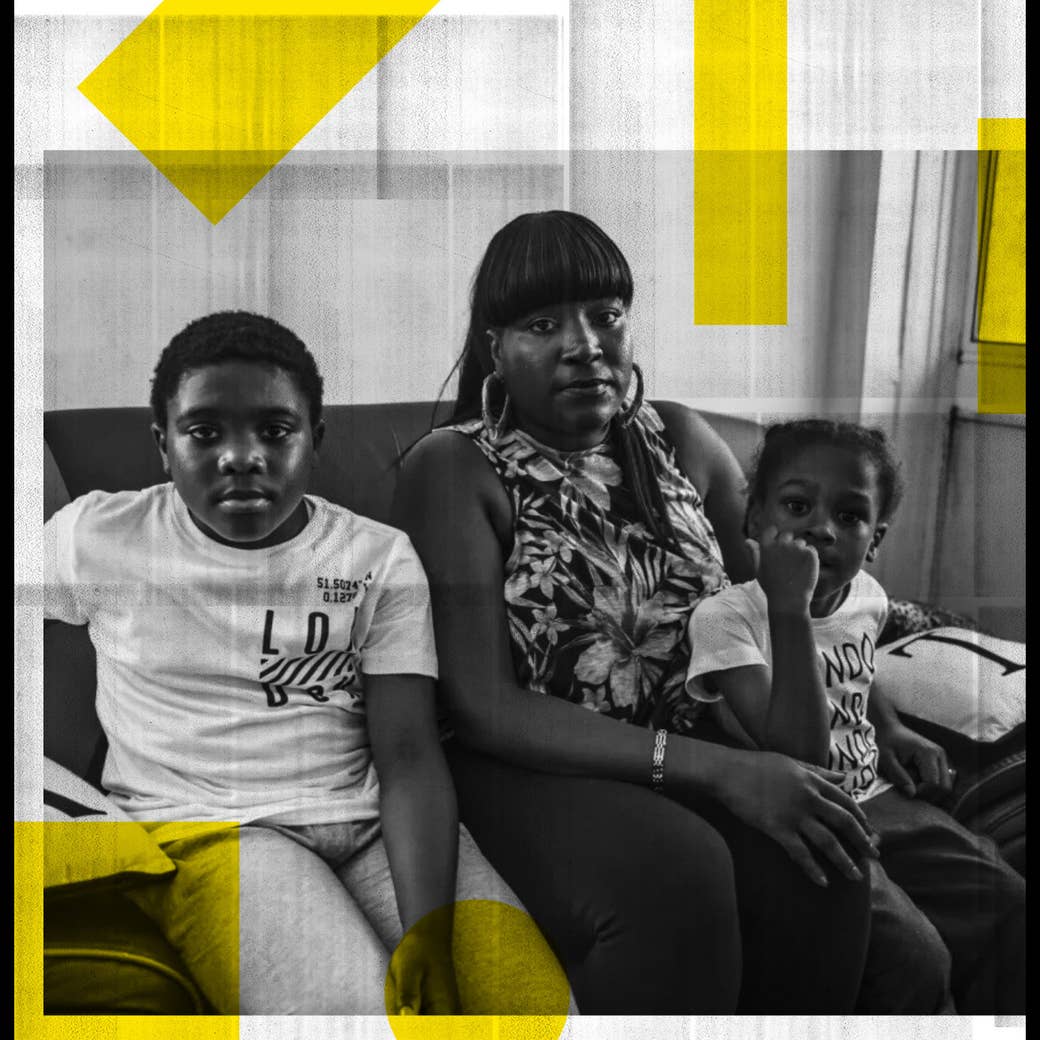

When BuzzFeed News uncovered the case of Cynsha Best, a woman born in the UK who always thought she was British but was told she was in fact Barbadian and should leave, the Home Office changed its handling of her case dramatically. After an online petition gathered more than 60,000 signatures and the Home Office came under intense political pressure, an individual caseworker at the department contacted Best saying he would like to resolve the situation and that she should apply to register as a British citizen. Best said it was the first time she had a named caseworker and that it was very different from her previous experience with the Home Office. Previously she was told that she needed to apply for leave to remain or make a voluntary departure.

The following month, the case of Shane Ridge, a joiner born and raised in Britain who was wrongly told he should leave the UK, was similarly fast-tracked. Within 24 hours of his story being published and going viral, Ridge had received an apology and was told he was automatically a British citizen.

Best told BuzzFeed News last year that the Home Office caseworker who contacted her after the story broke was different from any she’d previously spoken to and told her he had also handled the Shane Ridge case. “He’s the only guy who’s tried to help,” she said. “I think he must be the guy that deals with cases that are going through the media.”

McGill & Co, a Scottish law firm specialising in immigration, has had several cases fast-tracked after media attention. In one, a family who said they had been waiting for 18 years for a decision went on hunger strike outside the Home Office’s Glasgow building. Once the strike was reported by the BBC and local press, a meeting was immediately scheduled for the following week and confirmed by fax. Before the meeting took place, their visas had been granted.

One of their solicitors, John Vassiliou, said: “I and others at my firm would never in the past have had any contact with the media about any of our cases, but since the increased evidence of U-turn decision-making, it now almost seems like a more appropriate tool than litigation in many instances. It’s disappointing for me as a lawyer as it completely undermines what we do and suggests that, rather than following normal procedures and channels to get a correct outcome, it’s better to seek publicity and your case will be resolved.

"My disappointment is that if I or one of my clients ask the Home Office about a case, we get no response or they say no, but when a case publicised in the media portrays the Home Office in a negative light, then all of a sudden it’s different.”

Like many working in the immigration field, however, Vassiliou is relieved that the change in strategy at least creates a means of addressing the errors that come to light. “It isn’t necessarily a bad thing,” he said. “They’re trying to troubleshoot the worst of the cases, but if they dealt with all cases promptly and fairly in the first place, they wouldn’t need to. From the Home Office’s point of view, it’s probably better to have a few highly skilled workers troubleshooting, rather than overhaul the whole system. The problems that are creating these issues are so symptomatic they’re going to need a whole change in culture to combat it.”

In the aftermath of the Windrush scandal, Rudd said she was “concerned that the Home Office has become too concerned with policy and strategy and sometimes loses sight of the individual.” Deciding to fast-track cases which got publicity was Rudd’s way of addressing individual failures, but lawyers and judges say there is a systemic problem that urgently needs to be addressed.

Exactly 50% of all Home Office decisions that are appealed in the immigration tribunal are now overturned, the highest proportion on record. The situation has even prompted judges to speak out about the poor quality of Home Office decision-making — and the waste of public resources in pursuing court cases.

A surge in the number of controversial immigration cases reaching the media coincides with two acts of parliament that drastically reduced people’s ability to challenge Home Office decision-making. The first, the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO), took public funding for a lawyer away from almost all immigration cases not relating to asylum or detention. Then the Immigration Act 2014 took away the right to appeal a decision in most cases, leaving people with no means of challenging the Home Office.

Steve Valdez-Symonds, Amnesty International UK’s refugee and migrant rights programme director, has closely observed Home Office decision-making since 1999. He said: “Removing appeal rights has contributed to the fact that for so many more people there isn’t a way of redressing a wrong decision by the Home Office. Years ago you’d go to a lawyer, receive legal aid if you couldn’t afford that lawyer, and exercise your right to appeal. Now that’s been stripped away.

“Even if you retained your appeal right, you lost your legal aid right. What happened, particularly between 2013 and 2015, really deprived many people of any means of challenging what the Home Office had done to them. So what can they do? Try to get the interest of their local MP or journalists. You essentially try to get publicity for your case because there’s nothing left.”

BuzzFeed News revealed earlier this year that the number of people given public funding to fight an immigration case is lower than in any previous quarter on record. Just 6,609 people were given legal help or representation in their immigration case in the three months to September last year.

Valdez-Symonds says the handling of high-profile cases serves to highlight how poor the service is for ordinary people. “This different approach for people who’ve managed to draw significant public and media attention to their plight leaves most people caught in the immigration system absolutely nowhere. It leaves them in detention, on the streets, suffering huge distress, thrown out of the country that’s their home. This is resources being committed to PR not being committed to making sure people’s rights are respected.

“Things have got so bad, and been so badly exposed for them, that it would be impossible for them to say with a straight face ‘we don’t make bad decisions’. They acknowledge now that they make bad decisions but are trying to contain how widespread it is recognised as being. Their primary concern is not that the Home Office is treating people with respect and fairness.

“Instead of creating a system where officials care for people’s rights — enabling them to establish the status they have or are entitled to — you have a system where officials are concerned about protecting themselves, their department and the aims and targets of a department which is carefree about, even wants to disrupt people’s lives.”

A Home Office spokesperson said: “There is no immigration and citizenship casework team which works specifically on high-profile cases.

“The cases cited were dealt with by different immigration casework teams.

“All immigration and citizenship cases are reviewed in line with the Immigration Rules.”

Yet lawyers say the shift in the Home Office’s approach is so notable that they are already changing how they operate. Colin Yeo, specialist immigration barrister at Garden Court Chambers, said the department’s responses to media reports mean he is now much less cautious about advising his clients to get publicity. “Previously I’d have advised that press attention was a two-edged sword because stories can develop in unhelpful directions, and anyway, the Home Office and most judges would not be terribly impressed by publicity or public support. They would have thought it was self-serving, essentially. Now I would say that publicity is definitely a worthwhile risk, at least if the person’s situation is one which will be viewed sympathetically in the press and the Home Office might conceivably grant the visa if they think about it rationally.

“It is an awful lot cheaper and quicker than going to court to get a decision reversed. The appeal success rate is now 50%, but waiting times can be as long as 18 months for an appeal and legal costs run to thousands of pounds.”

The “culture of disbelief” at the Home Office is a phenomenon that has been tracked by academics for decades now. Asylum targets were introduced by Tony Blair’s Labour government in the 2000s, and from 1993 to 2006, the UK passed six asylum and immigration acts that promoted policies of greater immigration control. Over two decades, these policies reduced the rate of refugee recognition from 80% to 20% at the initial decision phase.

But Yeo believes that since Theresa May was home secretary, the sceptical culture within the department has grown and been exacerbated by increasingly complicated rules. This has led to poorer decisions and therefore a rise in controversial cases coming to public attention. “You just didn’t have the ‘computer says no’ culture that you have now, where the rules have been really tightened up and really detailed and it’s easy to make mistakes. They’ve removed human discretion from the rules and replaced it with an attempt to code things, which just doesn’t work and results in very inhuman decisions.”